I come from a hardcore Protestant world, a world in which we did not do “saints.” Even though I have spent much of my adult life, first as a graduate student, then as a professor, in Catholic higher education, I am still somewhat confused by and uncomfortable with the very notion of “sainthood.” I resonate positively with one of the main characters in Albert Camus’ The Plague who, when described as a “saint” by another character, responds that “sanctity doesn’t really appeal to me . . . What interests me is being a man.”

What makes a person a saint? Is there such a thing? Is there a difference between sainthood and moral excellence? Is sainthood a proper goal for a human life, or is it something one stumbles into? As I often do, I look for answers to such questions in literature.

A recurring character in Louise Penny’s Chief Inspector Gamache series of mysteries that Jeanne and I are currently binge-reading raises the saint issue in an interesting way. Dr. Vincent Gilbert abandoned a lucrative medical career to live in and care for a community of people with Down syndrome. Based on that experience he wrote a book called Being, by all accounts a memoir of staggering honesty and humility. Staggering particularly because Dr. Gilbert abandoned his family to enter this community, walking back into their lives years later to find that his alienated son and wife want nothing to do with him.

Dr. Gilbert is temperamental, a contrarian by nature, very full of and in love with himself, and is generally disliked by everyone in town. These contradictions have earned him the title “The Asshole Saint” among his family and acquaintances who know and don’t love him.

In Bury Your Dead, the sixth installment in Penny’s series, Vincent is living in a cabin deep in the Québec woods because his family refuses to let him live with them at their hotel and spa in town. Inspector Beauvoir, another recurring character in the series who is recovering from serious gunshot wounds received a few weeks earlier, finds himself in the cabin when Vincent rescues him from a snowmobile mishap. As Vincent tenderly cares for the feverish Beauvoir, the Inspector compares his current situation to his previous medical care over the past weeks.

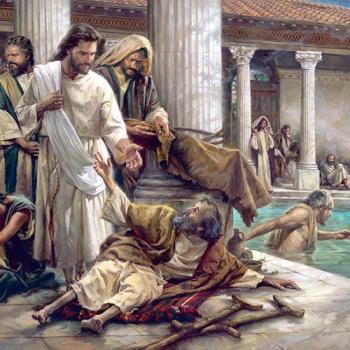

He’d been touched by any number of medical men and women. All skilled personnel, all well intentioned, some kind, some rough. All made it clear they wanted him to live, but none had made him feel that his life was precious, was worth saving, was worth something . . . [Vincent’s] healing went beyond the flesh, beyond the blood. Beyond the bones.

I have written before in this blog about the difference between “fixers” and “healers,” a difference that Inspector Beauvoir is taking notice of. The ability to recognize the value and dignity in another person, regardless of their status or situation, is one of the hallmarks of a healer—and perhaps a saint.

Less than a page after Inspector Beauvoir’s observations about Vincent’s healing abilities, the men enjoy a meal together while listening to a hockey game on the radio. Before long Vincent says something judgmental and nasty about Beauvoir’s culinary preferences, as much in character as Vincent’s tender care a page earlier. “The asshole was back,” Beauvoir notes. “Or, more likely, had been there all along in deceptively easy company with the saint.”

I have not yet finished Bury Your Dead, but a bit over half way through I have a sneaking suspicion that Vincent might have committed the unsolved murder that the Inspector and everyone else in town is seeking to solve. I won’t reveal down the line if my suspicions are correct—if I did, Louise Penny would have to kill me. But a killer saint might be a stretch—it’s challenging enough to come to grips with a saint being an asshole.

Or is it? When Camus’ character in The Plague says that he is more interested in being a man than being a saint, I suspect he is drawing a false distinction. Saintliness need not require rising above one’s humanity or leaving it behind. Instead, I prefer to think of saintliness as entirely compatible with being human—warts and all. The Protestant in me has always bristled a bit at Catholic veneration of the saints, primarily because raising them to veneration status removes them from the daily human grind and places them beyond the reach of reasonable human aspiration.

I enjoy finding out that Thomas Aquinas had an eating disorder and that Sister Teresa of Calcutta could be a bitch and was hard to get along with. Why? Because it tells me the excellence that sainthood represents is a matter of being fully human. Each of us can learn to see another person as more than a problem to be avoided or solved, to be attentive to the other in the manner that their humanity deserves. Each of us can learn to be healers, in other words—even if we still occasionally are assholes. That’s what incarnation is all about.