A few months ago, the gospel reading from Luke prompted our rector and my friend Mitch to suggest that Jesus is not someone you would ever want to invite to dinner. Why? Because Jesus’ behavior and the stories he told indicate that he had little interest in or patience with the way things are “supposed to be done.”

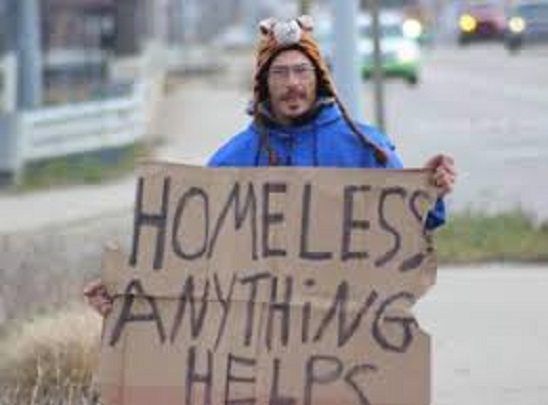

For instance, Jesus suggests that when you throw a dinner party, you should not invite your best friends and closest family, the people who you know and love the most and whose presence is guaranteed to make the evening a success (who also happen to be the people who are likely to extend a return invitation to you in the future). Rather, “invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind . . . because they cannot repay you.” Which makes me think locally.

In Providence, and I suspect in many locations, it seems that every busy intersection has a person or two standing with a container and a homemade sign that says something like “Homeless—anything helps. God bless you.” There has been a lot of chatter in various places about where all these people came from, are they really homeless or is this actually an organized scam, and so on. Jesus not only would not ask those questions, but he would also bring all of these folks along to your house for a meal if you invite him to dinner. So think carefully before you invite him—there’s no telling what he might do or say.

In an earlier story from Luke, Peter’s mother-in-law is sick with a high fever, Jesus heals her, “and immediately she arose and served them.” The word gets around, of course, that the healing man is in town, and as evening falls everyone with anything wrong with them either makes their way or is brought to Jesus. Throughout the night he heals them all. As one might expect, he’s exhausted by the time morning arrives and, as introverts will do, “he departed and went into a deserted place.” But showing a typical lack of respect for an introvert’s need for solitude and battery recharging, “the crowd sought him and came to him, and tried to keep him from leaving them.” Just a normal twenty-four hours in the life of a guy in high demand who also happens to be the Son of God.

So what are we to make of such stories if one professes to be a follower of Jesus and to at least be on the fringes of Christianity? My natural and immediate reaction from my earliest years has always been twofold. First, this guy was strange. Second, his being both human and divine equipped him to do stuff that normal human beings can’t do. Neither of those reactions is profound or unusual; it’s difficult to know what one is supposed to make of the gospel stories, particularly if they are intended to provide us with guidance for how to live a human life.

But not long ago I came across an “out of left field” observation about Jesus in action that jerked me up short. A couple of summers ago, Jeanne spent three weeks at an extended conference and workshop in Pennsylvania at a place called “Global Awakenings,” returning with much to be thankful for and much to share. All of the speakers and teachers she spent the weeks with can be listened to on-line, so I spent a good deal of time listening to and becoming acquainted with what these folks are up to.

I enjoyed and learned a great deal from my listening, but I resonated particularly with one fellow named Bill Johnson. A few days after we listened together to one of his talks, Jeanne said “I have something from one of Bill’s books that I want to read to you.” Here’s what she read:

Jesus could not heal the sick. Neither could he deliver the tormented from demons or raise the dead. To believe otherwise is to ignore what he said about himself, and more importantly, to miss the purpose of his self-imposed restriction to live as a man. Jesus said of himself, “the Son can do nothing.” He had no supernatural capabilities whatsoever. He chose to live with the same limitations that man would face once he was redeemed. He made that point over and over again.

Jesus became the model for all who would embrace the invitation to invade the impossible in his name. He performed miracles, signs, and wonders as a man in right relationship to God . . . not as God. If he performed miracles because he was God, then they would be unattainable for us. But if he did them as a man, I am responsible to pursue his lifestyle. Recapturing this simple truth changes everything.

“Wow!” I said—“Holy shit!” I thought—“That’s really out there.” One of several endorsements at the beginning of the book describes the author, Bill Johnson, as “one of the nicest persons I know, and one of the most dangerous.” That’s not an overstatement. Because if what he writes about Jesus is true, then there is no place for those of us who profess to follow Jesus to hide.

One of the great theological and doctrinal debates in the early Christian church had to do, not surprisingly, with how we are supposed to understand Jesus. Human? God? Both? The winner in the debate, as embedded in the Nicene Creed that Christians in many churches recite every week, was “Both.” Which is, of course, very confusing. Various groups have tended to emphasize one aspect over the other ever since.

My own tendency has always been to embrace the human side of Jesus rather than divinity if forced to choose, a tendency that over the past several years has evolved into a strong resonance with incarnation, the divine choice to be in the world in human form. I’m convinced that this was not a one-time deal. God continues to be in the world in human form, in you and in me. The passage from Bill Johnson’s book resonates fully with a strong embrace of incarnation. So far so good.

But as many, I tend to waffle when it comes to the miracles of Jesus. Amazing things happen in his wake everywhere he goes; all he has to do is show up. It’s easy simply to say “Well of course—he was the Son of God.” Bill Johnson’s argument is controversial, first and foremost, because it takes this “out” off the table. His argument also makes a lot of sense—it’s just that most followers of Jesus, including me, aren’t ready to hear it.

Athanasius provocatively once said that “God became man so that man might become God,” exactly what Bill Johnson is arguing. Jesus is an example and model of what a human being attuned to the divine is like, of what is possible for those of us who take our faith seriously. The idea of incarnation, of God working in the world in and through human beings, is a beautiful one—but it is also intensely challenging. Jesus told his followers that they would do greater things than he did, and that includes us. Are we sure that we are ready to “invade the impossible”?