Somewhere along the Great Chain of Being, we all have our place. That’s an old concept, and perhaps one that doesn’t fit our times as easily as it did in the past, but there’s much of it that still holds true.

Somewhere along the Great Chain of Being, we all have our place. That’s an old concept, and perhaps one that doesn’t fit our times as easily as it did in the past, but there’s much of it that still holds true.

From the ancients comes the idea that all things in reality can be located along a continuum—a “Great Chain,” as it were—hierarchized so that each thing possesses an attribute in addition to those that rest immediately below it, and lack an attribute possessed by those immediately above. Plants have life, so are above sand, which has only existence; but plants cannot move, so they are below animals.

Likewise, each entrant within a category can be hierarchized: The lion is the king of the beasts, because it possesses all of the prized attributes of creatures—strength, courage, beauty, etc. But because it lacks a soul, the prophets would rate even the most glorious of the leonine family below the most inglorious of the human.

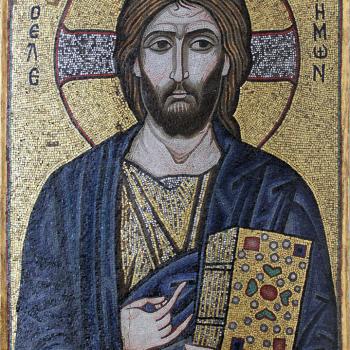

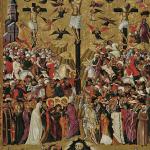

And among men, so goes the narrative, the Sovereign is at the top of the seating chart, with his subjects arranged in a cascading scale. Above men, at least for the time being, are the ranks of angels, from cherubim to seraphim (we are intended for a place higher than angels, once the eschaton arrives), and of course God Almighty is highest of all.

In drama, this idea has provided much fictive material. Because one of the greatest transgressions, perhaps the primordial transgression, is when a thing resists its place—either by aspiring to a role for which it is not fit, or by abdicating from a role for which it was made; pretending to more than one’s lot or deserting the lot that one possesses.

Drama, particularly Renaissance Drama (particularly Shakespeare), is full of it. It was, of course, the sin of Adam and Eve. When things leave their proper station, resist what they fundamentally are, the cosmos is upset: “Cry havoc! and let slip the dogs of war.”

For though nature is said to abhor a vacuum, she is not very good at either filling it or maintaining equilibrium. Things rush into the void, but often they are not apt for their new station.

Macbeth wants Duncan’s place, but look what good that did him; striving for a level too high, taking it by force, he brings the realm into turmoil. Similarly, by abdicating his throne, Lear puts ancient England—nay, all of creation—on the skids. There is no lack of pretenders and deserters in the world, nor a lack of those who will jockey for their places once they leave them.

What explains this itch?—this desire to look high and low, but seldom to rest? The irony is that we are slaves to our appetites—driven to seek things we cannot have or to abandon duties we should not forego; as such, we lose the freedom that comes from knowing our paths, from filling the clothes cut for us. High ambitions are a good thing, but they must be tempered by the realm of the possible, and the possible changes from person to person.

It is important to know what we are so that we can be what we are. It is important to reflect upon our gifts, upon what is our natural state, so that we don’t waste time. The Greeks counseled this above all, as their greatest aphorism was “know thyself.”

Granted, it is not always pleasant, getting acquainted with what you are. I recall hearing of a young girl who had a great comedic flair on the stage, acknowledged by all, but was heartbroken that she was never cast as the ingénue. She was the Nurse to another’s Juliet; the wise-cracking sidekick, the worldly lady in waiting, but never the romantic lead. She could not abide her lack of fortune, and so deserted what fortunes she had. Try as she might, she could not pull off the role of the beloved, as she was not made for that place; her talents betrayed her desires, but she could not see past them.

What a waste, it was said of her. Because she could not be what she wanted, she would not be what she was. A whole world of real possibilities was foregone in favor of bitterness over sheer impossibilities.

Today, this kind of stark lesson is not in favor. We are told that achieving what we want is only an amount of effort and heart. But while effort and heart are key ingredients to success (as is, I would add, a fair amount of luck), they must be spent in favor of a likely objective. Conquering obstacles is great, and our most worthy heroes have often come from the furthest back, but that is because they knew that what they were belied what they were told they were. They proceeded from a knowledge hidden from others, not from an irrational or overweening desire.

None of this is said easily; I know well that contentment is a hard thing to achieve. There is a negative connotation to it, too. “Playing it safe” is deplored, and if it means a lack of courage, it is deplored rightly. But a difference is worth noting; there is the refusal to take up the burden of what one is in favor of a lesser place, which is cowardice—a desertion; then there is the blindness of not wanting to be what one is in favor of a higher place, which is foolishness—a pretense.

“Rest there,” counsels the soul, when we have found what we are. But this rest is not one of inaction; it is rest from a search for that understanding; only when that search is over can we act, with great pitch and moment. For we can only be and do what we truly are.

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled,won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.