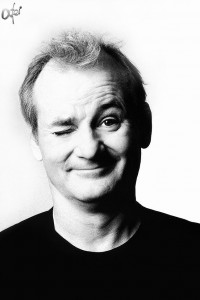

In Bill Murray’s long movie career, I don’t think he’s ever played a flat out bad guy. Neither to my knowledge has he ever been a geek. He’s been crazy from time to time, and he’s been on the wrong side of the law, but without fail he’s supremely likeable. Most importantly, he’s never been uncool (I am on record as saying he’s the coolest man on earth).

In Bill Murray’s long movie career, I don’t think he’s ever played a flat out bad guy. Neither to my knowledge has he ever been a geek. He’s been crazy from time to time, and he’s been on the wrong side of the law, but without fail he’s supremely likeable. Most importantly, he’s never been uncool (I am on record as saying he’s the coolest man on earth).

Fine directors have used him to great effect, Sophia Coppola, Lost in Translation; Jim Jarmusch, Broken Flowers; Harold Ramis, Groundhog Day; though none have capitalized on his talents as much as Wes Anderson.

Anderson, one of the most original, imaginative, and delightful of today’s directors has showcased Murray in Rushmore, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, The Royal Tenenbaums, Moonrise Kingdom, and offered him plum vignettes in The Darjeeling Limited and The Grand Budapest Hotel.

He’s always had his own way of going, lived within his own enigmatic code, and never ever disappointed. It’s difficult to isolate exactly what’s made him so distinctive, but I’m of the opinion that it has to do with sincerity.

If you look at Murray’s latest offering in Theodore Melfi’s St. Vincent, a nice, predictable film in which he plays a sloppy, gruff, drunken hero to a young boy who needs a world of help, you see a culmination of the things that comprise the actor’s talent.

In the story, there’s much to motivate the man’s disgust with the world. His house is coming apart, his wife is lost in dementia, and whatever luck he once possessed he’s squandered at the race track.

But in a thread of similarity with other Murray roles, there’s a fundamental decency about the guy that never allows him to fall off the floor. He doesn’t seek out the role of life guide for the hapless lad next door, and you’re never quite sure if he’s enjoying or merely enduring the modest improvements that he brings to the child’s circumstances.

Nevertheless, in his uniquely sad way, every word he speaks and every act he undertakes rings with truth. His character may not mean what he says forever, but he means what he says right then.

And that note of deep sadness to the man is his charm. Maybe melancholy is in some way the wellspring of much sincerity. It’s worth considering whether the sad have a greater propensity for authenticity than those strung with joy.

When we’re chastened, we don’t have the stomach, or perhaps the energy, for our regular set of lies. It takes a lot of vigor and spark to muster up deceit. We have to put our hearts into it. Most days, we’re up to the task, as nothing is pulling on us too hard. So we can grease the wheels of our progress with a few tricks and swindles to get us what we want.

But when we’re heartbroken—be the snap new and crisp and bright with pain—or old and sore and dull with memory—we have a harder time pulling off the regular act. If the ache is not completely debilitating, we muddle on.

Still, that weight in the pocket of our souls, that brick that pulls it down and distends it with such reliable elasticity, has at least one (perhaps more) salutary effect: it breaks our taste for untruths. It musters the same kind of forthrightness that sickness does; those who have the flu can most always be trusted.

And Murray has always had a case of the flu—personality-wise, that is. The more I think about it, those disposed to comedy share this ironic malady.

The Greeks knew that the line between the two was not a strong one; the laughing mask gave way to the crying mask quite easily—they are often either transposed or lie one atop the other. The curve of the mouth and the set of the eyes is only a matter of degree.

The most famous funnymen have born a sometimes deadly share of the gray sister, sadness—Peter Sellars was manic; Robin Williams—God rest his soul—was beyond the pale. But thus far, the Irish Midwesterner Murray has carried on and not succumbed.

There’s a good deal of bravery in such things, which I suppose adds the final bit of illumination to this character study. Those who are steeped in the shadows have a talent for shedding the light, and are often some of the bravest, albeit the heart-heaviest, of our witnesses to it.

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled,won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.