I do not know which to prefer,

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

—Wallace Stevens

Jewish Mindfulness Teacher Training Program instructions for this month:

“Choose a phrase from Psalm 30 or Hallel to begin and/or end your sitting practice every day. Use the same blessing every day. Memorize it. Notice if it changes your practice, if you recall it during the day, if it inspires awe or connection to life.”

How to choose?

Psalm 30: it’s shorter than Hallel, a section of the Jewish worship service, included on particularly joyous days such as the three pilgrimage festivals, in which all the psalms include the word hallel or the concept of praise. I can read Psalm 30 quickly and see if any verse calls out to me, and, if it does, I can work with that verse this month.

“Will dust acclaim You, / will it tell Your truth?” I read in Robert Alter’s translation.

Dead Men’s Praise, I think of Jackie Osherow’s marvelous book that includes “Scattered Psalms,” a group of poems that includes one based on Psalm 115: 17: “The dead cannot praise the Lord, / nor any who go down into silence.”

The language of Alter’s translation feels a little stiff, a little stilted. Even so, as I repeat it once or twice internally before closing the book, it is the verse that chooses me. In the interest of time, I’ll look no further.

I start the meditation timer for thirty minutes, strike the bell three times, close my eyes, settle on my bench, and start saying the verse. Is it after the third or second repetition that I wonder if I’ve chosen wisely? The first? Is this the verse I want to spend a month with? Is it likely to lead to any insight, the reward I seek for my discipline, my practice?

Will these words comfort me? My anxiety level is set by default on high. Right now, the beginning of a new semester in sight, it has risen to high anxiety. I could use something, anything safe to restore me to my factory default setting of anxious.

I should stop before I’m too far along with this morning’s practice, before I’m stuck with this verse—Will dust acclaim You, / will it tell Your truth?—for the month. I should open my eyes, open the book, read the psalm again, look for a different verse more likely to offer me the experience I’m seeking.

Or.

That’s where I get stuck.

I see now: that’s a practice, too, sitting with or. Options, paying attention to what arises when one has options. My experience of options? Indecisiveness.

My experience of options: self-doubt. I’m not smart enough, skilled enough to make the right choice.

My experience of options: fear. What if my choice is wrong? What if, in choosing this, I’m refusing that? What if, in choosing this, I’m losing the opportunity to experience that? Losing the opportunity to experience that and that and that and that and that and…sounds a little like death to me. And I’m afraid of death.

I’m stuck.

I stick with it: Will dust acclaim You, / will it tell Your truth?

And I remember, from the first time I went through the Jewish Mindfulness Teacher Training program, a few years ago, some readings of Buddhist texts about visualizing—in detail—the death and rotting of the body, one’s own body.

I’m flesh, warm flesh; I’m dust. I visualize it. It’s simple. And, to my surprise, to my delight, I’m not afraid. I’m relieved. Am I relieved because when it comes to this—mortality—there are no options? One day I will die.

Another morning: Will dust acclaim You, / will it tell Your truth? I’m following an instruction. I’m not intentionally thinking about these words, wondering what they mean, wondering if they express my questions. I’m thinking about just repeating the words without thinking about the words themselves.

Before I know it—after one repetition, two—I’m thinking about the course on the history and culture of Judaism I’ll begin teaching in a little less than two weeks. I’m thinking about the new text, Creating Judaism by Michael Satlow, that we’ll be reading, how I haven’t finished reading it myself for the first time, how I can’t really plan the class until I know how this particular book works.

My nerves are tremoring, my breath is shallow and fast, and underneath these thoughts, and at the same time, I’m noticing the physical manifestations of fear and panic. Will dust acclaim You, / will it tell Your truth? I’m trying to keep the verse going, when suddenly I feel, I see, I know: these thoughts, thoughts that trigger or are triggered by my ever-present fear of failure, will, one day, be dust.

Another morning: Will dust acclaim You, / will it tell Your truth? I wonder: until then, until dust, am I telling Your truth? Inadequacy, self-doubt: do I even know Your truth to tell? Let go of intentionally thinking and just repeat the words, open to whatever comes: will dust…Your truth, will dust…Your truth… will dust…Your—suddenly, a shift: I’m the one addressed here!

In a flash, I see my conversations with my hevruta (study) partner in the program, how I practice listening to her and how I try to pay attention to what arises in me as I listen to her and, in my response to her, how I try to share the truth of what arises—even when, as I speak, I’m questioning whether what I’m saying is helpful to her. I’m saying this, but could I, should I be saying that?

Or: I speak and, at the same time, I’m stuck again on or.

What I’m telling you is true. This is a practice. This is my practice.

Perhaps you, dear Lord, can tell me this: is my truth your truth?

Richard Chess is the author of three books of poetry, Tekiah, Chair in the Desert, and Third Temple. Poems of his have appeared in Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of IMAGE, and Best Spiritual Writing 2005. He is the Roy Carroll Professor of Honors Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. He is also the director of UNC Asheville’s Center for Jewish Studies.

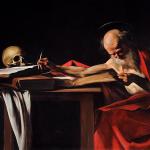

Photo by Balint Foldesi (Schwarzkaefer), used under Creative Common License.