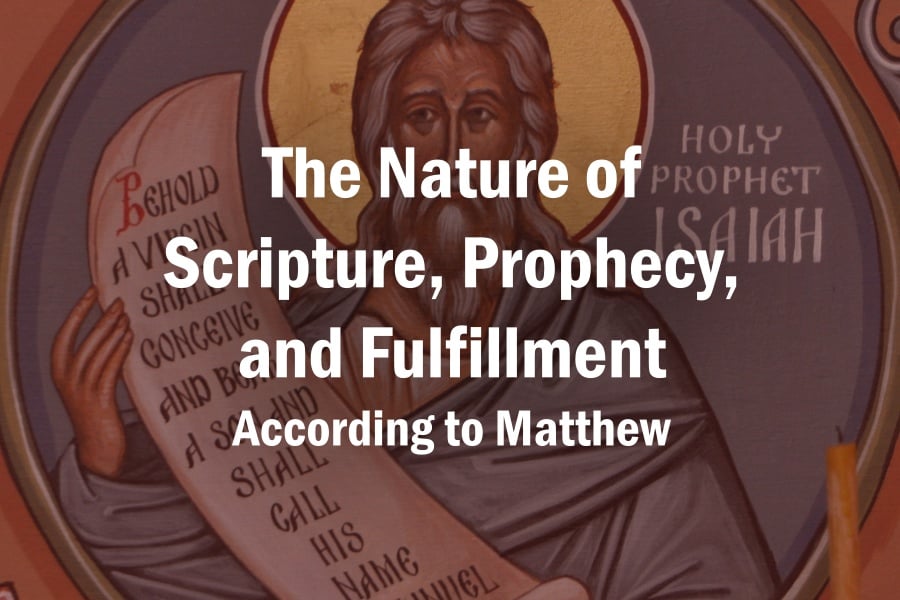

In the first two chapters of his Gospel, Matthew directs his readers’ attention to four different prophecies that he says are fulfilled in the story of Jesus. He will continue making such claims throughout the book, but these four provide an adequate base for us to begin examining how Matthew understands the nature of scripture, prophecy, and fulfillment.

We’ll take a look at them one by one.

Now all this has happened, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying,

“Behold, the virgin shall be with child,

and shall give birth to a son.

They shall call his name Immanuel”;

which is, being interpreted, “God with us.” (Matthew 1:22–23, WEB)

This is another one of those passages we’ve heard so many times that we tend to skim right over it. We all know that Isaiah predicted Jesus’ virgin birth, right? But did he really?

For starters, Isaiah 7:14 uses the Hebrew word almah, which is more accurately translated as “young woman,” rather than “virgin.” (See the CEB, CJB, GNB, NET, and NRSV for a few translations that get it right.) While an almah could be a virgin, she need not be a virgin in order to be an almah.

Furthermore, by looking at the context, we can see that the original prophecy could not possibly have referred to Jesus. According to the passage, Yahweh instructed Isaiah to prophesy to Ahaz, telling him that his enemies would not be victorious; in fact, their land would be desolate in 65 years (Isaiah 7:1–9). Yahweh then told Ahaz to ask for a sign, but Ahaz refused (Isaiah 7:10–12). In response, Yahweh offered a sign of his own, which happens to include the part we’ve all come to know (Isaiah 7:13–16).

But here’s the thing—that sign was given in order to prove how quickly the prophecy would come to pass. Remember, it had a 65-year expiration date. And the boy the sign foretold was not to reach maturity before it had been fulfilled. But this was written many centuries before Jesus was born! So how could it refer to him?

What about the name Immanuel—“God with us”? We tend to read it to mean that Jesus himself is “God with us.” It’s certainly true that Jesus is God with us, and it’s possible that Matthew alludes to this. But in Isaiah’s prophecy, it simply signified that God was with the people of Judah, rather than with their attackers. The boy whose birth Ahaz witnessed was not God in flesh.

So why would Matthew claim this passage as a prophecy about Jesus? We’ll come back to that. For now, let’s take a look at few more of Matthew’s prophetic claims.

He arose and took the young child and his mother by night, and departed into Egypt, and was there until the death of Herod; that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying, “Out of Egypt I called my son.” (Matthew 2:14–15, WEB)

Matthew here quotes from Hosea 11:1, which describes how Yahweh brought the people of Israel out from Egypt. The passage goes on to show that Israel was repeatedly unfaithful to Yahweh, despite his continual care for them. But it does not prophesy about the future at all. Nothing seems to point to a coming messiah.

Then that which was spoken by Jeremiah the prophet was fulfilled, saying,

“A voice was heard in Ramah,

lamentation, weeping and great mourning,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she wouldn’t be comforted,

because they are no more.” (Matthew 2:17–18, WEB)

This time, Matthew inserts a quotation from Jeremiah 31:15. The original passage has Yahweh speaking to Rachel, the mother of Israel. Rachel weeps for her children, not because they have been killed by a power-obsessed king, but because they have forsaken Yahweh and brought about their own ruin.

In the verses that follow, Yahweh comforts Rachel, showing that hope still remains for Israel. Rachel’s children will repent and be restored.

But when he heard that Archelaus was reigning over Judea in the place of his father, Herod, he was afraid to go there. Being warned in a dream, he withdrew into the region of Galilee, and came and lived in a city called Nazareth; that it might be fulfilled which was spoken through the prophets: “He will be called a Nazarene.” (Matthew 2:22–23, WEB)

Matthew’s citation here is particularly interesting because it doesn’t exist in the Hebrew scriptures. No Old Testament prophet says anything like, “He will be called a Nazarene.”

Many guesses exist as to Matthew’s source for this prophecy, most having to do with a play on similar-sounding Hebrew words. For example, Matthew may be alluding to the Nazirite vow (Judges 13:5, 7), but then again, Jesus did not follow Nazirite restrictions. Or Matthew may be thinking of the passage from Isaiah: “A shoot will come out of the stock of Jesse, and a branch [neser] out of his roots will bear fruit” (Isaiah 11:1). Or, given that Matthew specifies “prophets” rather than “prophet” in this instance, he may be referring to a composite of several passages.

Whatever Matthew has in mind, one thing is for sure. He is not taking any passage in its original context and applying a straightforward interpretation.

In all four of these instances, Matthew applies creative eisegesis, deliberately taking the passages out of their original contexts.

I’ve been studying the Bible for a long time, and I’ve read a lot of books on proper biblical interpretation, but I can’t remember ever seeing eisegesis presented as a good thing.

Eisegesis (reading ideas into a text) is contrasted with exegesis (reading ideas out of a text). While exegesis attempts to discern the original meaning of a text, eisegesis causes a text to say something that was not originally intended. Take pretty much any course on biblical interpretation, and you’ll come out of it with a very clear lesson: exegesis is good, and eisegesis is bad.

I guess Matthew would have failed that course.

But he isn’t interested in the literal face-value interpretation of these texts. And he certainly isn’t concerned with whether they’re inerrant or not. He’s just looking for ways to make a connection from the scriptures to Jesus.

So as Matthew is going through the scroll of Isaiah (reading the Greek Septuagint translation, rather than the original Hebrew), he notices a prophecy about a virgin (or parthenos in the Greek translation—a word which does imply virginity) who was to give birth. He then remembers how Mary had told him about her miraculous conception of Jesus.

Continuing to read, he sees the name Immanuel. What a wonderful way to describe Jesus! And so, with the prompting of the Holy Spirit, he writes it down as a prophecy fulfilled by Jesus. No, the prophecy did not originally refer to Jesus, but that didn’t stop Jesus from stepping into the prophecy to fulfill it anyway.

And as Matthew is going through the scroll of Hosea, he considers how Jesus’ life mirrors and recapitulates the history of Israel, even including an exodus from Egypt. (But unlike Israel, Jesus always remains faithful.) So he writes down another prophecy as fulfilled by Jesus.

And as Matthew is going through the scroll of Jeremiah, he reads of Rachel’s lament over her children, and it reminds him of the children slaughtered in Bethlehem. But just as Yahweh promised Rachel that her children would be restored, so too does Yahweh promise that these children of Bethlehem will be restored through the resurrection.

Time after time, Matthew points his readers to prophecies that were not originally about Jesus. But Jesus claims these prophecies for himself. He assumes them, and he fulfills them. He brings to them a much richer and more perfect meaning than the prophets had ever intended.

For if Jesus is Lord over all, he is certainly Lord over scripture.

This is the sixth post in my “Blogging through Matthew” series. If you missed the previous post, be sure to check out “A King of the Jews, Pagan Magi, and God’s Radical Inclusivity.”