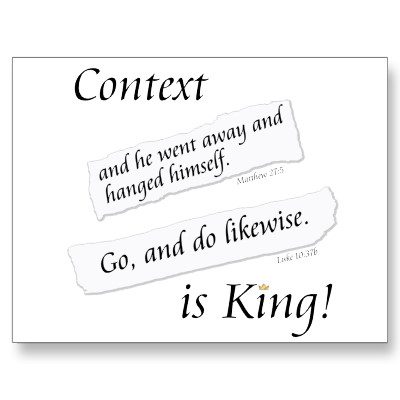

“Context is King” is should be the first thing Christians learn as soon as they start reading the Bible.

My family and  friends can recite this adage in their sleep because they hear me say it all the time. Unfortunately, I have found I shouldn’t expect even seminarians to grasp the significance of this majestic phrase.

friends can recite this adage in their sleep because they hear me say it all the time. Unfortunately, I have found I shouldn’t expect even seminarians to grasp the significance of this majestic phrase.

“Surely you exaggerate,” you might say, “what is all that significant about a simple little three word phrase?”

Let me first explain what the phrase means and then consider alternative ways of thinking.”Context is King” means that, in whatever passage we’re studying, the literary and historical context is primary in determining the meaning of the text. The sections immediately prior and following our passage bear greater weight that far contexts (whether elsewhere in the Bible and especially historically/culturally).

What does it mean?

Context is King affirms two core values or principles:

(1) Always interpret Scripture with Scripture.

(2) Our most basic goal is always to discern the author’s intended meaning.

When we read Scripture, if context is not king, then what will be sovereign over our interpretations?

All too often, it is the set of notes at the bottom of our study bibles. Other candidates include our pastor, parents, or the last book we read or mp3 sermon we heard. In one way or another, our own cultural assumptions will ride roughshod over the author’s original intent. (On that topic, see the excellent book called Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes.) On our worst days, if we’re honest, we will admit more sinful motives will prevail.

Two Common Problems

How does this go wrong? I couldn’t even begin to scratch the surface of the questions. For now, I’ll highlight two common substitutes often used by Christians who want to be “biblical.”

First, people assume theological conclusions before they even begin reading the text.

This leads people to jettison the immediate context and turn to a different passage in order to validate (or “proof-text”) their predetermined conclusions (which may be correct in another context). Therefore, we fight for a correct biblical idea (drawn from some other text) at the expense of the immediate point being made by the author in the original passage, which may not be the same point being made elsewhere at other times.

Second, for fear of becoming “liberal,” one becomes excessively literal.

What does that mean? Basically this––we completely ignore things like genre and/or overly constrict the author’s ability to use words in the same flexible way that we do everyday. If there would ever be literature with disorienting language and imagery, it would be that which concerns the beginning and end of all things, e.g. creation and the apocalypse.

Finally, take the famous example among Calvinists/Arminians, who debate the meaning of “all” in various verses. I’ve heard more than a few sarcastic oversimplifications to this effect: “‘All’ means ‘all,’ period.”

The whole question is complicated by a simple example from our school days. At the beginning of a class, the teacher would ask, “Is everyone here?” When the students say “Yes,” she does not snap back, “No, you are wrong! President Obama is not here! John Piper isn’t in class! Neither is Peyton Manning.” What’s the point? In that context, “all” clearly does not mean “all.”

When it comes to actually respecting this rule, it’s easier said than done. We want to be king. We want to be right. We don’t like be restricted. I challenge you to spend a week or two trying to interpret passages you read each day, but without cross-referencing other books.

(Normally, it would be good to compare the larger context, but for the sake of experimenting and self-discipline, see what you discover by never leaving the immediate context.)