In Christian Political Witness, the authors repeatedly lament the divide between “public” and “private.” Why?

It is often thought that freedom is only possible by parting the political seas. In order to enjoy the “miracle” of American democracy, we must separate politics from Christian faith. However, in CPW, it is argued that common notions about the church-state relationship have an adverse effect on God’s people.

Christian Faith is Personal not Private

Jana Bennett (chapter 6) explains some of the practical implications of our verbiage about identity. In particular, she exposes the idolatry of individualism by examining common ways people talk about family and state (120ff). Even among Christians, common rhetoric presumes a fundamental division between the private (family) and public (state) spheres.

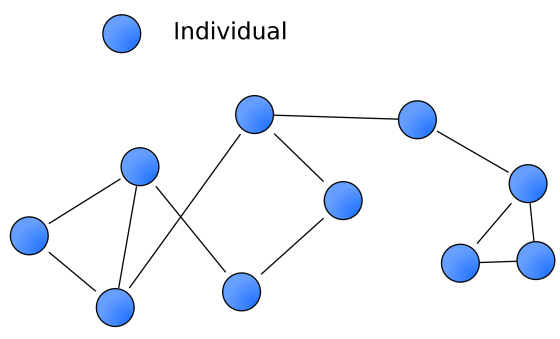

“Individualism,” as a basic orientation, makes the individual an idol inasmuch as personal freedom becomes the authoritative standard for ethical decisions. By fragmenting identity—separating individual from community— public ethics is rendered impossible since each individual presumes sovereignty in making moral decisions.

That division ultimately–– ironically––causes people not to take responsibility for their actions. After all, what happens in private (so it is thought) should be separated from one’s public life. Therefore, Bennett concludes that what is wrong with the world is that individuals fail to take responsibility for himself or herself.

She (citing Reinhard Huetter) astutely observes,

“ . . . we tend to understand the church as one entity among others, equivalent to the ways we name business, government and families as entities. As mentioned above, our language about the church as private entity matches this kind of language” (124–25).

In other words, people view the individual in relation to the church in a way parallel to the family/state division mentioned above. The problem is now pretty obvious. By dividing the public and private spheres, we effectively dismember the body of Christ, i.e. the church.

Thus, Bennett argues that western individualism undermines a Christian political witness. Although she mainly speaks to American Christians, her words apply across multiple cultures. Christians overlook the political/ethical implications their “private” family lives have on their “public” lives. Thus, for example, some people will question the church’s credibility when we talk about issues like marriage and sex.

Preaching that is Personal and Political

What are some of the practical implications of Bennett’s essay?

1. Making an idol of the individual leads to indifference for others.

As Bennett puts it, “We imitate the world, rather than being witnesses for Christ, because we are drawn inward by the ways the arguments about private, public, family, and state are made” (121). To idolize the individual inevitably idolatrizes oneself. Thus, individualizing identity eventually leads to isolation and exclusion. Why? In part, it effectively nullifies identity by severing our self-understanding from our relationship to others.

In that sense, there is no personal (private) apart from the political (public).

2. Theologians and church leaders need to broaden the way we talk about identity.

Westerners tend to talk about personal identity based on one’s differences. However, there is another side to identity–– how we are similar to those around us. In Chinese, the former refers to the “little me” (小我). The latter is called “big me” (大我), who I am within my relationships. In fact, human identity is determined by both our differences and similarities.

By gaining an appreciation for both aspects, I suspect we would sort out a number of theological and ethical debates. In addition, global theologies could more easily emerge that complement and correct tradition western theologies.

3. Evangelism should emphasize the “who” question not simply the “what” question.

Christ calls us into a family and a kingdom. Our fundamental problem is not simply what we’ve done. Humans have broken relationship with God and one another (Gen 3, 4, 11). We want “face.” People can get “face” not only because of what they achieve (i.e. distinguishing themselves from others); in addition, one gets face based on group identity (thus, one’s commonality to others).

The traditional evangelical gospel message tells people to repent of what they do but does not fundamentally reorient their sense of identity, desire for face, and the privileging of relationships such that exclusion becomes the norm. When our gospel calls people to give allegiance to king Jesus, conversion means leaving one group and joining a new one, namely, the church, Christ’s global human family.

4. We have to redefine “politics” in terms that are personal.

Notice, I did not say “private.” Sin is always personal because it is people who sin. Sin is not abstract. Yet, sin is never truly private. Inevitably, it permeates all we are as it disorients our view of Christ, the world and ourselves.

Consider a simple question: Was John the Baptist “political”?

When John told Herod that Herod shouldn’t be with his brother’s wife (Matt 14:3–4), was John being “political” simply because Herod was a politician?

In Luke 3:12–14, John tells tax collectors and soldiers what they shouldn’t do. Was John being political then?

Photo Credit: CC 2.0/pixabay