I often hear people say that missionaries are not the people who should be doing the contextualization for the Chinese church. Instead, they should let nationals do the contextualization. They are the ones who can contextualize best.

That sounds right. Unfortunately, however, it’s merely an ideal and a half-truth at best.

The truth is this––Chinese do not naturally contextualize theology for a Chinese context.

This observation is evident to anyone who has spent significant time among Chinese Christians across the country and has visited their training centers. At least among evangelical churches, one will not find a distinctly Chinese pattern of thinking about the Bible and theology. Rather, the typical theology found among Chinese Christians varies little, if any, from conservative, Western churches. In particular, I refer to emphases and expressions.

I’m not suggesting that a genuinely contextualize theology would contradict traditional, Western theology. Nor am I saying there isn’t a diversity of theological perspectives. That’s obviously false.

What would we expect….?

What would we expect from a distinctly Chinese theology? A genuinely contextualized theology would at least supplement (if not correct) Western theology. We would expect that non-Western theologies would expose blind spots and bring balance to traditionally neglected themes.

For example, we would expect a Chinese theology to address a number of critical ideas, which are concerns shared by both Chinese people as well as the Bible. Most obvious among these themes are honor-shame and collective identity.

Instead, other than the language, it is difficult to identify any meaningful differences between theology in the Western church and that found in the vast number of Chinese fellowships.

Why do Chinese not contextualize?

Here are a few factors that stifle contextualization within the Chinese church.

1. Chinese Union Version (CUV, 和合本)

The Chinese Bible hinders Chinese self-theologizing. One of the most well known problems in the CUV is its translation of sin as “crime” (罪). First of all, the word does not inherently mean “crime.” If we restrict ourselves to a sheerly legal metaphor, then of course “crime” expresses the idea of sin.

However, the Bible is far more diverse in its way of expressing the problem that we call sin. For example, Rom 1:18–23 describes unrighteousness as the dishonoring of God. The Old Testament routinely depicts Israel’s sin as that of adultery.

Unfortunately, the CUV’s narrow translation automatically forces the Chinese Christian to assume a legal framework when talking about sin and thus salvation. Consequently, other metaphors and themes will be marginalized and regarded as analogies at best.

2. Chinese respect authority and tradition

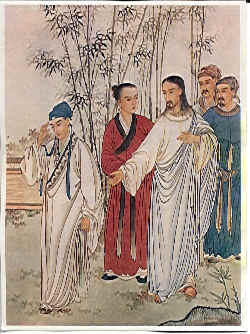

Chinese people respect authority and honor tradition. Therefore, when Western missionaries uncritically present theological ideas in a very traditionally Western way, then the Chinese believer will naturally accept this framework as “gospel”. Accordingly, they will emphasize doctrines and texts that speak most clearly to a Western context. All the while, these basic doctrinal categories and questions do not cohere easily with normal Chinese patterns of thinking.

Missionaries can confuse the theology commonly found in churches with a genuinely contextualized Chinese theology. The believers’ acceptance of Western theology however does not confirm that Western theology is essentially the same as Eastern theology. The Chinese people’s humility to honor tradition and authority becomes a pathway whereby they are subtly “judiazed” by Western teaching.

3. Lack of theological training

There is very little standardized theological training being done in the Chinese house church. I specifically refer to accredited theological education. The point of highlighting “accreditation” is not to say that higher level degrees are important to spiritual maturity. Instead, accredited theological training provides some measure of quality control.

There is a far amount of training that comes from “theology from a box” type programs. These 3–4 day sessions have value but they have definite limitations. For instance, they are not normally contextualized for a Chinese context in particular. Also, those course are often taught through translators.

Furthermore, those programs offer a pretty restricted scope of classes. This is because they are often pre-written to cover 8–10 basic and broad subjects. Then they are translated into Chinese and perhaps 10 other languages.

As a result of these things, those course teach doctrine but not necessarily the additional critical thinking skills that Chinese Christians need to address the problems they face in China.

4. Lack of exegetical skill

Those who have been heavily influenced by the Western church tend to emphasize systematic theology. Most missionaries are more conversant in theological doctrines than they are in how to do exegesis. (As illustration, let’s not forget how few missionaries received rigorous training in the original languages, not to mention the application of that knowledge in the task of exegesis).

Not surprisingly, a lot of training stresses the doctrines of systematic theology. These can be learned, memorized, and dogmatically defended. However, that does not guarantee that people will know to interpret the original meaning of a text within its own context. More typical is the instance where a pastor presupposes an answer and then goes to the Bible to confirm what they already heard from a prior teacher.

Contextualization however requires both exegetical skills as well as a grasp for the grand biblical narrative. These are two spheres of training that are not usually emphasized by missionaries and thus the Chinese believers whom they taught.

The above factors are just a few of the major reasons Chinese do not naturally do contextualization. Until these problems are addressed, it will be difficult for Chinese Christians to develop Chinese theologies.

Photo Credit: CC 2.0/commons.wikimedia