People sometimes prefer to have two nicely divided categories: good or bad, right or wrong, love or hate, . . . . Similarly, in debates or conflicts, we are prone to label others either “for us” or “against us.”

The debate over human origins has been plagued with false dichotomies. Some of the ones I hear most often include: conservative/liberal, literal/allegorical, perfect/fallen.

In The Lost World of Adam and Eve, John Walton breaks the traditional mold. He interjects fresh terms into the conversation about creation. His categories will not doubt confuse some readers. Ironically, these same ideas will simultaneously bring greater clarity of understanding for others.

A few questions help illustrate the point.

1. Should an earthquake be called “evil” in the same way murderers and child predators are called “evil”?

2. Are “innocent” and “perfect” synonyms?

I would say “no” to both questions. For instance, the earth does not conspire to bring us harm for its own gain. Although a baby in some sense can be called “innocent,” the infant is not “perfect” in any meaningful way.

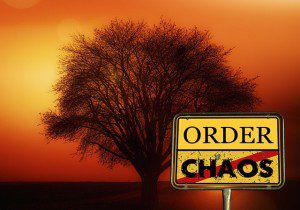

Order, Disorder and Non-order

Walton says that Gen 1 tells at least a similar story as told by other ancient creation accounts.

The creation account depicts God the One who brings order out of (primordial) chaos. Chaos represents “non-order,” not “disorder.” Disorder is “evil.” By contrast, the ancient listeners/readers of Genesis would not necessarily regard non-order as “evil.”

(As a brief aside, Walton does not deny that God ex nihilo created the material universe. He simply says we can’t use Genesis 1 to arrive at that conclusion.)

At this point, Walton challenges some fundamental assumptions. For example, in this and previous books, he notes that ancient cultures had different ideas about existence and non-existence. If something was regarded as lacking a function, i.e. non-order, then is did not have “existence” (e.g. the sea, a desert).

According to Walton, humanity was called to serve God by bringing greater degrees of order to a world of non-order. It was not until the Fall (Gen 3) that disorder enters the world.

According to Walton, humanity was called to serve God by bringing greater degrees of order to a world of non-order. It was not until the Fall (Gen 3) that disorder enters the world.

Death is an aspect of non-order, Walton says. However, when humans are denied access to the tree of life, we are no longer able to overcome our mortality. Consequently, death becomes lingering evidence of disorder.

Sin and Sacred Space

This interpretation does not totally dismantle Christianity’s view of Genesis; however, Walton will certainly cause people to rearrange some of the furniture in their theological house.

For instance, God’s work of “ordering” can be reframed in terms of Temple-building. God creates sacred space, one that will have neither non-order nor disorder.

Walton makes his own suggestions as to how this perspective of Gen 1–3 reorient our view of sin. Of course, readers will discern implications for other matters, like salvation and the work of Christ.

For many, Walton’s ideas will appear too novel to be reasonable. However, he would remind those readers of two points.

1. The past 100 years have yielded many significant insights into the ancient world that were not available to past generations when they interpreted Genesis. Scripture has authority, not tradition interpretations.

2. Walton’s reading of Genesis 1–3 coheres well with the rest of the Bible’s story and the imagery it uses.

For more elaboration, you’ll have to read the book (and perhaps some of his other ones as well).

In some ways, Walton’s interpretation is very “Chinese” in that it finds a “middle way.” People in Eastern cultures appreciate balance. Perhaps there is wisdom here for us as we real Genesis.

Whenever a debate is polarized between two strict alternatives, we ought to consider whether there might be a way to reconcile the legitimate observations of the competing groups. In The Lost World of Adam and Eve, Walton gives a careful and constructive starting place for finding a “middle way.”

Credit (Egyptian wall painting): geralt via pixabay (CC 2.0)