How do Chinese churches organize themselves? How does Chinese culture influence church structure? What are the implications?

Networks, not Denominations

Protestant Chinese house churches organize themselves as “networks” (团队) rather than “denominations” (宗派). Arguably, they look similar to Western denominations. However, a few distinctions are noteworthy.

First, most networks do not formally originate from traditional Western denominations. Certain church networks are influenced by a given tradition (T). Yet, churches are not necessarily planted from T-denomination. Nor do they identify themselves with T-denomination.

Denominations traditionally are defined theologically, according to some set of doctrines. By contrast, Chinese church networks share regional and relational affinities. They expand along relational networks. As a result, church networks are rooted particular regions (though they will spread to other locations). To belong to Y-network likely entails adopting a personality or view typical of people from Y-region.

The Structure of the Chinese Church

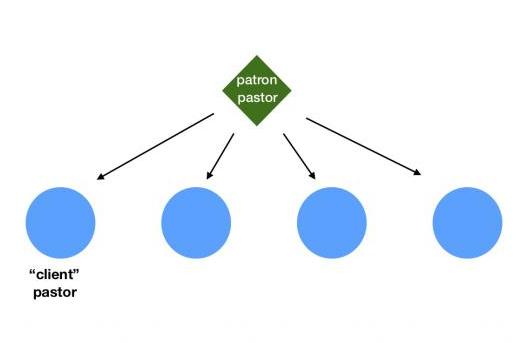

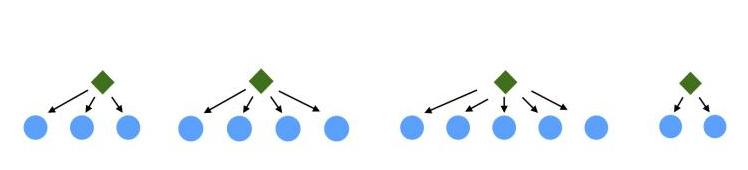

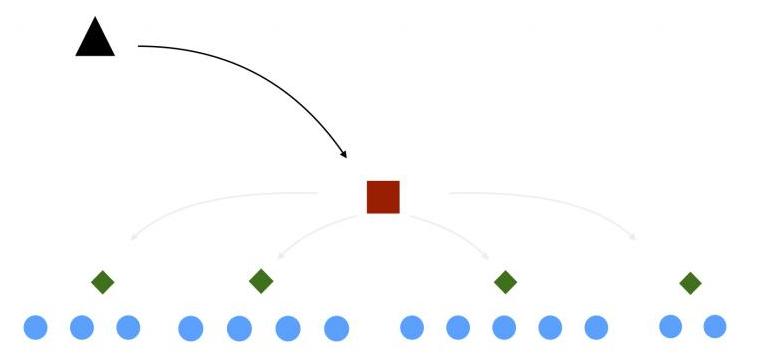

A network branches out like a system of tree roots, akin to the structure of “Amway.” See the diagram below.

One pastor (Pastor C) could have 4-5 other pastors under him or her (and thus the churches they shepherd). One of those pastors (Pastor H) might lead another 2-3 pastors (each with their own church(es)). Pastors on the same level in the hierarchy often function as an advisory council for one another. This group does not serve as a presbytery.

One pastor (Pastor C) could have 4-5 other pastors under him or her (and thus the churches they shepherd). One of those pastors (Pastor H) might lead another 2-3 pastors (each with their own church(es)). Pastors on the same level in the hierarchy often function as an advisory council for one another. This group does not serve as a presbytery.

A variation on this model is also common. Instead of each church having one pastor, a group of pastors might rotate among a group of churches. Thus, 4 pastors might regularly rotate in preaching to 7-8 different churches.

Pastors as Patrons

The upcoming Patronage Symposium has spurred me to reflect on ways patronage, reciprocity, etc. influences the Chinese church. This requires thinking about how the church organizes itself.

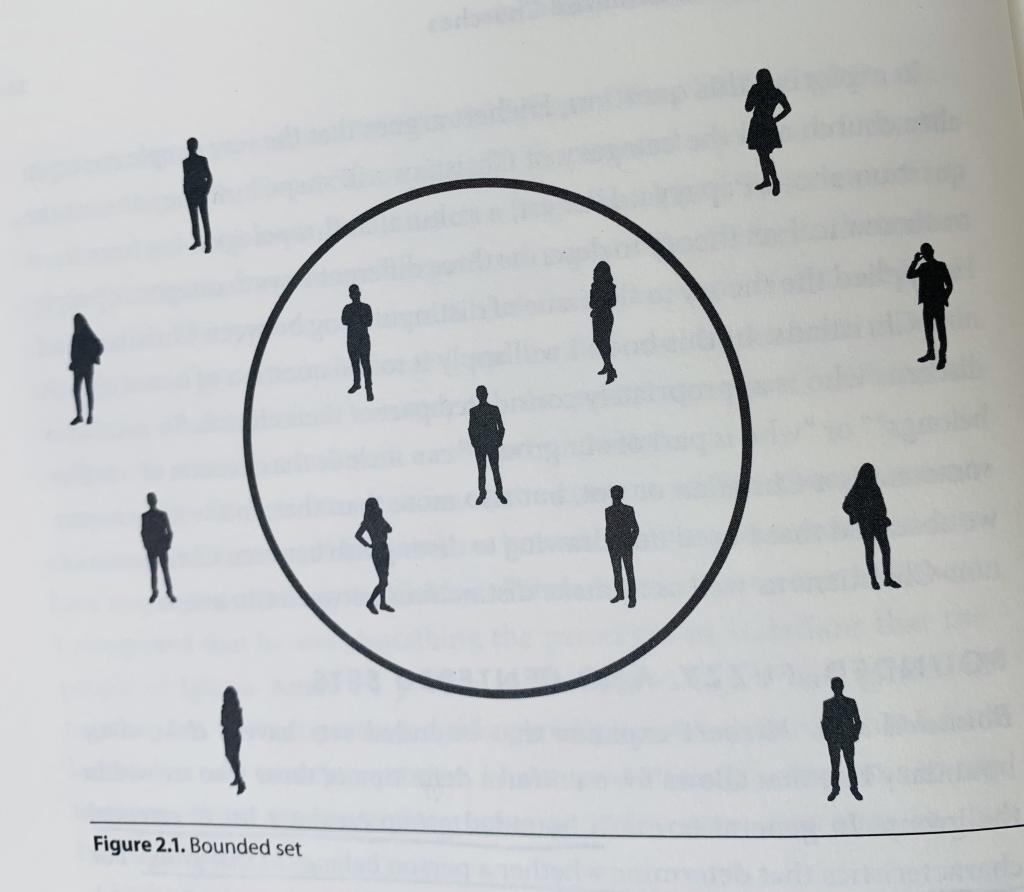

For our purposes only, I’ve used patronage language to clarify the function of the above pastoral relationships. (Chinese Christians don’t use explicit patronage terminology). Below, church leaders who are higher in the hierarchy will be called “patrons.” Pastors lower in the hierarchy are called “clients.”

To read about leadership in collectivistic churches, click here.

The patron chooses the pastors under his supervision. He provides them with various kinds of help. Besides training and encouragement, the patron offers financial support. A pastor wishing to plant a church depends on the generosity of the patron for counsel and financial backing.

The patron can also choose to ordain a client. Ordination in Chinese churches is required for someone to be reckoned a “pastor.” Prior to ordination, (s)he is considered a 传道 (perhaps translated “preacher”). The patron will provide endorsements (e.g., when one wants to attend seminary). He lends credibility to the client in the eyes of others. He introduces “clients” to contacts who can offer practical assistance in a given area (e.g., training, resources, skills, etc.). In effect, the client inherits the patron’s relational network (guanxi wang).

Networks (and sub-networks) have different ways of managing funds and thus regulating how patrons influence clients. In one approach, churches under his supervision pool their money, which a patron then distributes as (s)he decides. Alternatively, some churches give the patron a portion of the tithes received. Patrons draw on their experience and inside knowledge to allocate resources as they think best.

A Fusion of Faith Traditions

Chinese ecclesiology is a blend of multiple theological traditions. A group meeting at a single location is just as likely to be called a “church” as would a large group of churches. Accordingly, a Chinese Christian might say Pastor C’s church has 40 people (at a single location), 130 people (at multiple locations where he preaches), or 4,000 people (counting all the locations led by pastors under his supervision). A Westerner might call the latter a “network,” whereas Chinese simply call it a “church.”

Structurally, Protestant Chinese house churches resemble the Anglican church more closely than other denominations. This organization is more pragmatic than theologically driven. Almost all these churches practice credo-baptism. A large number (most?) churches have a singular pastor/elder who serves as the spiritual leader. In some cases, another person is recognized as a “pastor/elder” yet only provides financial support for the church. He who pays has a say.

In recent years, people have reported of the growth of “reformed” theology among Chinese Christians. This statement needs qualification. Increasing numbers of Chinese churches have a reformed soteriology. Such churches could be described as “reformed Baptist” churches. Very few Protestant churches in China practice infant baptism. Thus, churches increase in size by baptizing new believers.

The form and function of church polity depend more on personal relationships than external criteria, whether theological creeds or a formalized system. What does this approach mean for pastors? They must pay close attention to maintaining quality relationships with other pastors.

It also creates a range of challenges and opportunities. A “client” pastor must ensure he doesn’t transgress his patron’s theological boundaries. Naturally, one must consider how and where (s)he gains theological training. After all, clients want to make certain the patron pastor approves.

To read about pastor-centered Chinese churches, click here

A Few Implications

I’ll mention a couple of implications. Others no doubt exist.

-

Evangelism and Missions

A church’s strategy and ministry priorities can be subject to the patron’s approval, regardless of client or congregation’s will. For instance, if a local church wants to send missionaries to another country or people group, the patron pastor needs to approve the initiative as well as the mission candidates. Likewise, a church planting strategy or evangelistic methods should suit the patron’s liking.

-

Church Discipline

Because churches are tied by pastoral relationships, they approach to internal discipline differs from churches in other cultures. We should first recognize that church discipline is extremely rare, especially given the importance of harmonious relationships in China. Nevertheless, where the situation occurs, individual congregations have little if any authority. Congregations cannot remove a pastor. Only a patron pastor disciplines a client pastor. If a new pastor is needed, the patron will assign one to the local church under him.

Bible + Culture = Theology

Depending on a person’s theological persuasion, one will either say Chinese ecclesiology is biblically sound or culturally syncretistic. Chinese churches certainly represent an amalgamation of theological views. Whatever one’s judgment on the particulars, we would do well to recognize a simple fact; namely, our cultures, sub-cultures, and personal backgrounds invariably influence our theologies, including our ecclesiology.

That statement is no criticism of theology in general nor any specific tradition. It’s the nature of contextualization. “All theology is contextualized” goes the saying. I hope these observations foster humility to learn from one another and examine the Bible with fresh eyes.