Few subjects are so paradoxical as popularity.

Few subjects are so paradoxical as popularity.

- “Popular” kids often are the most liked and disliked people in school.

- Youth seek it above anything else; as adults, popular kids don’t always fair well.

- Although adults bemoan the popularity contests of adolescence, these dynamics still exist in companies and organizations.

- Popularity is both helpful and harmful.

These are a few observations noted in Popular: The Power of Likability in a Status-Obsessed World (by Mitch Prinstein).

In this post, I’ll highlight a few of Prinstein’s observations then consider potential implications for the church and the work of missions.

Who is “popular”?

Popularity is our earliest introduction to the concept(s) of honor & shame.

Of course, popularity is just one dimension of a much larger dynamic. Its influence on our lives (not only childhood) is far reaching. For anyone who wants to understand how honor-shame cultures work, popularity is a common starting point.

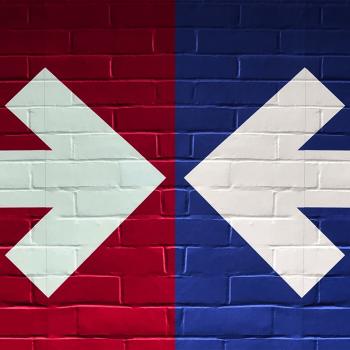

Prinstein distinguishes two forms of “popularity.”

-

Status

-

Likeability

Both involve approval within groups. But they have important differences. “Status” refers to one’s power, recognition, visibility, etc. The meaning of “likeability” is self-evident and depends on things like generosity, selflessness, sociability, etc.

The qualities that make people popular (or not) tend to reproduce themselves in different groups. This makes sense. We tend to carry similar social behaviors with us (e.g. sense of humor, aggressiveness, manner of speaking, agreeability).

Some aspects of popularity vary across cultures. For instance, popularity and social aggressiveness are more closely linked in the West than in China, where such personalities are less liked and less popular.

Should we seek popularity?

You’d think this would be easy to answer. It’s not. As relational beings, we’re wired to desire acceptance, to be liked. This is an essential aspect of belonging to a group. As worshipers, we also grasp the value of status.

For example, those who were popular as youth tend to have more difficulty in establishing close friendships, satisfying romantic relationships, and are more likely to engage in riskier social behaviors.

What about unpopular people? Intriguingly, longitudinal studies show they have more health problems and higher mortality rates than those with average or high popularity in their younger years.[1]

Who versus Why?

Contemporary society has turned social recognition into a commodity. The right persona secures a certain degree of power. Not surprisingly, people begin to think happiness depends on the quantity of people who know them, who like their FB page, etc. Their social status becomes the measure of their worth.

As Prinstein suggests, happiness is more closely linked to likability. This is what creates quality relationships (not merely quantity of “friends”). So, the key question is not “who” knows us but “why” are we known.

Maintaining status is external dependent, contingent on others’ opinions. C.S. Lewis’ “Inner Circle” analogy is apt in that those with status live within an “inner circle” (socially speaking); status is competitive and thrives on differences and exclusion.

On the other hand, likeability is correlated to comradery, compassion, and cooperation. It brings people together around some set of common behaviors or values.

At different stages of life, the criteria for high status changes, whereas the characteristics that make us likable are more stable.

Implications for Mission & the Church

In the church, the effects of popularity are subtle but significant. We are all susceptible to popularity’s social influence. This is one reason marketing is big business. Popular products, books, and movies grab our attention.

“Popularity” becomes a form of social validation, a safeguard that an item, trend, or idea is worth our attention.

How does this manifest in the church? Simply because speakers, books, and ministry methods become popular, that popularity itself generates even greater popularity among the masses. Their ideas and methods are either normalized or assumed to be beneficial.

It’s only natural to yield to the herd mentality. Generally, it’s a good rule of thumb to consider others’ opinions and practices, since we individuals cannot know and test everything. Persistent individualism is not virtue.

However, consider how popularity influences our theology and ministry methods.

How many gospel tracts, theological ideas, etc. have been used simply because the originator had the money and position to popularize it. In other words, their ideas gained popularity because of their name, their institution, affiliation, or some set of unique circumstances.

We can become too dependent on popularity as a filter for both orthodoxy and orthopraxis. We cease looking at ideas with a critical eye. I am often stunned that certain blogs and websites receive the attention they do. The posts and articles frequently lack substance. Their arguments are muddled or trite. This is not healthy for the church.

One can too quickly confuse the popularity with what is profound.

The potential implications of this subject extend well beyond what I can imagine or write about in this post. I encourage you to reflect on the topic yourself. Leave a comment or write your own post exploring ways that popularity (in its various forms) can affect the church and its ministry.

- For a shorter NY Times article “Popular People Live Longer” by Prinstein, click here.

- For Prinstein’s free online course “Psychology of Popularity,” click here.

[1] What is striking about this finding is that the study does not include suicides.