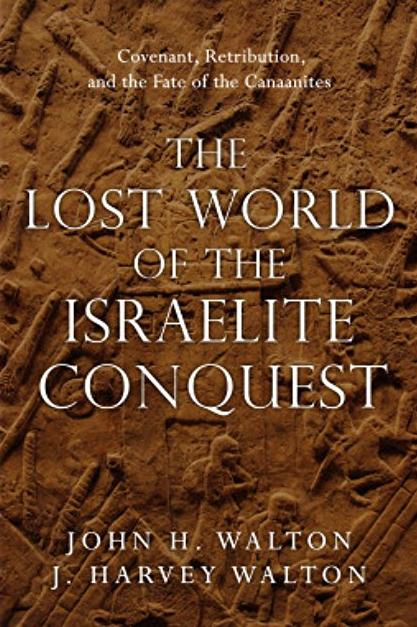

Although John Walton never shies from controversial topics, his recent book is bold, even by his standards. In The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest (TLWIC), he takes up multiple contentious subjects yet without being cantankerous.

It is cowritten with his son, J. Harvey Walton, who was the lead writer. Nevertheless, this latest installment of The Lost World series matches the tone and methodology of his prior works, which I’ve previously reviewed here and formally.

Why review this book?

The title could mislead readers. I even wondered whether I would want to get it. He certainly addresses the conquest issue, but, along the way, he deals with various related and interconnected matters.

Why review books like this? Here are a few reasons.

- Everything begins with interpretation. Few consistently and simply demonstrate sound methodology as does Walton.

- The book raises several apologetic problems, such as God’s seeming “genocide” of the Canaanites.

- Many themes and topics have a systemic influence on our theology. Slight adjustments can have a ripple effect on how we read other passages.

- Walton does with culture in Old Testament interpretation what I suggest we do when doing contextualization.

The latter is significant for anyone who seeks to contextualize in a biblically faithful and culturally meaningful way.

Readjusting our Expectations

Walton divides TLWIC into 21 propositions. (In this series, I’ll blog only through certain key sections of the book.) The first three propositions lay the foundation for his interpretive and theological method.

Prop #1: Reading the Bible Consistently Means Reading It as an Ancient Document

Prop #2: We Should Approach the Problem of the Conquest by Adjusting Our Expectations About What the Bible Is

Prop #3: The Bible Does Not Define Goodness for Us or Tell Us How to Produce Goodness, but Instead Tells Us About the Goodness God Is Producing

The first proposition is fundamental to everything Walton writes. Accordingly,

“Central to our approach to how the conquest should be interpreted and understood is that the Bible, while it has relevance and significance for us, was not written to us” (p. 7).

Understanding that idea is one thing; letting it practically shape your reading and theology.

Cultural Rivers

The chapter uses the metaphor of a river to describe the phenomenon whereby we either naturally “go with the culture” or “swim upstream against culture.” Going with or against is not the main point. The Waltons remind us that we do not even swim in the same “cultural river” as the biblical writers and their original audience.

The point is important for anyone concerned with recognizing how the Bible exerts authority within culture.

The Bible was not written in order to transform ancient thought to resemble modern thought, and neither was it written in order to simply affirm the values and ideas of the ancient cognitive environment and stamp them with divine authority for all time. (p. 9)

More specifically,

In order to translate properly, we have to understand the internal logic of the source, apply that logic to the text (as opposed to our own), and then rephrase the conclusion in terms that correspond to our logic. The conquest is a war, but if we want to understand the event, we cannot do so by using our modern understandings about war—what it is, what it is for, whether it is good or evil, how it should be waged, and so on. Instead, we have to look at the account in light of ancient understandings about war. (p. 10)

Beginning with “Why?”

Many others will be surprised to find they overlook a seemingly obvious point. We can hardly understand what the Bible says (i.e., means) until we grasp why it exists.

If we misconstrue its purpose, we will likely get much else wrong, if not in meaning, then in emphasis or focus. They write,

“We propose that the Bible is given to us not to provide a list of rules for behavior but to reveal God’s plans and purposes to us, which in turn will allow us to participate with him in those plans and purposes” (p. 15).

As shocking as this claim might sound, it makes sense, particularly when we keep in mind what they are not saying. The Waltons do not deny the Bible contains commands and that we can glean insight from it regarding how to live in God-honoring ways.

The authors remind us that expectations drive our search for the Bible’s meaning. Two approaches are typical.

(1) People see the Bible as a timeless rule book.

At best, this notion is a half-truth. “Timeless” might refer to the Bible’s authority but we ought not to mean the prescribed manner that all people –– spanning time and place–– should live.

(2) Other people assume the Bible describes the actions God uses to bring about “goodness” in the world.

This view is fraught with problems, the most significant being the presumption that we know what that “goodness” is. Most readers unquestionably presume such “goodness” is human happiness (cf. pp. 19–23). This was not the ideal of ancient near easterners. Order was.

What is “goodness”?

Furthermore, “The Bible does not tell us what God’s ideal of goodness is because the purpose for which the Bible was written does not require us to know that.” (p. 27).

We must consider the implications of a God-centered reading versus subtle human-centered readings. They add,

The Bible does not tell us what that final product is; the Bible tells us how to do our part on the assembly line [using a factory analogy]…. [It is possible] we will be able to contribute to the procedure, but we ourselves will still produce no goodness. This is because, once again, the Bible was not written to tell us how to produce goodness; it was written to tell us how to participate in the goodness that God is producing. (p. 27)

Finally, the Waltons foreshadow what will eventually follow from these statements.

The text does not affirm that killing the Canaanites is good, because killing the Canaanites is not the objective of the conquest. The objective of the conquest is to fulfill the covenant, which in turn is only a part in a larger process leading up to the new covenant, which in itself is only a part of the process leading up to the new creation.

The conquest account was not written in order to tell us what we should do; it was written to teach us about what the Israelite covenant is, which in turn is necessary for us to know what the new covenant is, which in turn is necessary for us to know what specifically we are supposed to do in our own cultural context to play our part in the new covenant. (p. 28)

But to grasp these conclusions, we will have to continue reading. More to come in upcoming posts.

What strikes you so far about the first few propositions? Do they raise any questions in your mind?