Recently, a student generously gave me brewed coffee, to which I said thank you. On cue, he replied “应该的” (i.e. I ought to do it). We were studying Romans in class. So, thinking I’d be clever, I said, 应该的不是恩典, indicating “It’s not grace if it’s what you are supposed to do.”

Unfortunately, I was wrong. I didn’t realize it however until I reflected more on John Barclay’s Paul and the Gift. I was once again reminded that Christians have a lot to learn from tradition Chinese culture.

Although Barclay writes about ancient Mediterranean cultures, he could easily be commenting on contemporary Chinese culture.

To understand why, recall John Barclay’s insights about the manifold nature of grace (see part 1, part 2). In Paul and the Gift, he particularly demonstrates the link between reciprocity and the giving of gifts (i.e. grace). He writes,

But even the slightest knowledge of antiquity would inform us that gifts were given with strong expectations of return––indeed precisely in order to elicit a return and thus create or enhance social solidarity (11).

Barclay spends half of his book showing how this plays out in Romans and Galatians. When God gives grace, even He seeks reciprocation. Specifically, He expects us to respond in faith, obedience, and genuine worship.

This idea––even divine grace requires human reciprocation––might at first seem confusing and a backdoor way of making grace “conditional” rather than free.

Is Grace Really “Free”?

It depends.

A closer look at Chinese culture might help us to understand why. In some ways, even non-believing Chinese can grasp important aspects of grace that go unnoticed (and are even denied) by most Christians.

Consider the interaction with my student. Rather than simply saying “thank you,” Chinese often say 应该的(i.e. “It’s what I’m supposed to do”). Many Christians recoil to hear explicitly that someone was nice merely out of “duty,” as if (s)he had to do it. We don’t want people to feel “burdened” to give us gifts or do kind deeds. After all, grace is supposed to be free.

However, Chinese know the truth: grace is never completely free.

Many Westerners sense this upon arriving in China. They often squirm when receiving gifts from Chinese friends. English teachers will wonder if gifts are actually bribes in disguise. If Chinese friends takes you out to a very nice meal, you might begin to wonder on what their “real agenda” is.

Also, I consistently find Westerners uncomfortable when it comes to exchanging gifts/favors. Westerners do not like to be “indebted” to others.

Grace Establishes Guanxi

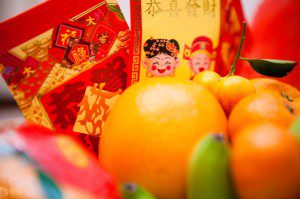

By contrast, Chinese intentionally use gifts to establish & enhance relationships (guanxi).

It is only natural that the gift’s recipient will eventually reciprocate with another gift or favor. The exchange continues indefinitely as the relationship deepens.

Just as exchanging gifts (i.e. grace) gives “face” and expresses approval of others, it makes sense that refusing gifts can be interpreted as rejecting the gift-giver. (Of course, I don’t refer to social mores require an initial refusal of a gift.) If you persistent to reject a gift, you in effect convey that you don’t want relationship (guanxi) with that person.

This dynamic creates a quandary for typical Westerners, who do not want to be indebted to another person. In this situation, one suspects the Chinese person understands something about grace that Westernized Christians miss.

Genuine relationships are about mutual indebtedness.

Gift-giving (i.e. grace) is an important part of creating and strengthening relationships. Gifts can express solidarity, celebration and concern. Therefore, relationships marked by sincere love actually seek to deepen mutual bonds of indebtedness.

Consider the alternative. What do you call a relationship without ongoing mutual indebtedness? A business transaction. That is, one party provides a service, the other pays the bill, and each goes his own way.

Grace without the expectation of mutual reciprocity is simply not grace.

What I Should Have Said

My student was right. He showed me “grace” because it was 应该的 (what he ought to do). However, I would prefer to have said something else to distinguish Christian grace.

If my “ought to” is also my “want to”, then it is grace.

[如果我“应该的”也是我“想要的”,它就是恩典].

In an upcoming post, we’ll look at Scripture and answer key objections.