Why does the Bible say we are “God’s enemies”?[1] The reason is less obvious as some think.

Atonement and God’s Enemies

Debates about atonement eventually come to this point. Compare a few common ideas.

1) God sees people as enemies

Those affirming penal substitution say: Because we sin, we are God’s enemies. Therefore, he will pour his wrath on us unless Jesus is punished in our place. This camp emphasizes God’s enmity towards sinners; i.e. God regards us as enemies (even while loving us).

2) People see God as enemies

Those opposing penal substitution argue that penal substitution directly contradicts Jesus’ command to love your enemies. This group suggests that people regard God as their enemy (not vice versa).

3) Both

Others throw their hands in the air (in my opinion) and simply assert, “It’s both”, with little or no defense from Scripture. Commenting on Rom 5:10, N.T. Wright says,

“We should not, I think, cut the knot and suggest that the enmity was on our side only. God’s settled and sorrowful opposition to all that is evil included enmity against sinners.”[2]

Though Wright says this, some people worry about his emphasis on “Christus Victor.” According to this theory of atonement, Christ on the cross defeats sin, death, and demons. In this way, he frees us. According to many contemporary versions of “Christus Victor,” God regards Sin, death, and demons as enemies, but not us.

Naturally, some might wonder whether Christus Victor undermine the Bible’s teaching that we are God’s enemies?

Who is whose enemy?

Let’s first note the passages that describe people as God’s “enemies.”

For if while we were enemies we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son, much more, now that we are reconciled, shall we be saved by his life. (Rom 5:10)

For many, of whom I have often told you and now tell you even with tears, walk as enemies of the cross of Christ. (Phil 3:18)

Also, Col 1:21 (cf. Rom 1:30; 8:7).

I suggest we rethink a common assumption held by conservatives. Conservatives generally suppose we deny God’s wrath against sin if we don’t interpret being God’s “enemies” as “God regarded us as enemies,” i.e. had enmity towards us.

This is not true.

What do “enemies” do?

Allow Scripture to interpret Scripture. In the famous “love your enemy” passages, what do enemies do?

You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you. (Matt 5:43–44)

But I say to you who hear, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. To one who strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also, and from one who takes away your cloak do not withhold your tunic either… (Luke 6:27–29)

What pattern do we see? Enemies seek our harm; they do not seek our good. What do we not see? Enemies are not (necessarily) people we hate.

Our feelings toward others do not determine whether they are “enemies.” Enemies decide whether they are enemies.

Elsewhere in the New Testament?

How does the New Testament describe enemies? Compare James 4:4.

You adulterous people! Do you not know that friendship with the world is enmity with God? Therefore whoever wishes to be a friend of the world makes himself an enemy of God.

Verse 4a explains v. 4b. “Enmity with God” is equivalent to what? “friendship with the world.” Who has a friendship with the world? People. So, it is the individual who has enmity making him an enemy of God.

In summary, saying “we are God’s enemies” means “we see God as an enemy.”

Here are other passages that reinforce the point.

- “Have I then become your enemy by telling you the truth?” (Paul in Gal 4:16)

- “you enemy of all righteousness…” (Acts 13:10; Paul to Elymas)

- “…that we should be saved from our enemies and from the hand of all who hate us;” (Zechariah prophesies in Luke 1:71)

Cf. Matt 13:25, 28; Luke 19:27, 43.

“Enemies” are defined as those who hate us. This is essential; it’s not (necessarily) true that enemies are “those we hate.”[3]

What about God’s wrath?

Some people might hesitate to accept these observations. They fear we might subtly deny God’s wrath against sinners. That conclusion, however, is impossible for anyone reading the Bible.

The Bible is replete with references to God’s wrath. In fact, just before Paul calls people God’s “enemies” in Rom 5:10, he says,

“Since, therefore, we have now been justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God” (5:9).

With a few possible exceptions, the New Testament routinely describes God’s wrath as something in the future. Yes, God’s wrath comes upon all who ultimately reject him. By contrast, Jesus “delivers us from the wrath to come” (1 Thess 1:10).

The New Testament does not depict God as one who simultaneously loves those he hates.

Perhaps, someone might deduce that idea via systematizing; namely, claiming God loves everyone then citing OT passages where God hates people (Ps 5:5; 11:5). However, doing so requires we strip verses from their context, assume highly debatable interpretations of certain passages, and basically treat the Bible as a systematic theology book and not a text to be understood within context.

Who is our “enemy”?

Who is “our enemy”? What does it mean to love our enemy?

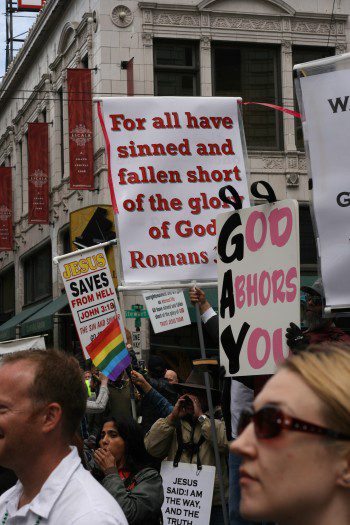

Jesus’ command to love our enemy does not mean we should love people reluctantly despite the fact we actually hate them. While pastors would not put it so directly, this “grit and bear it” attitude is precisely how people talk about Jesus’ commands.

The problem with that common impression is obvious. If “love your enemies” means “love those you hate”, we have a contradiction unless we do some verbal gymnastics.

One reason this insight matters is this: we ought not assume Christians will hate people but can simply “love them,” whether by tolerating them or doing good things for them. Jesus does not command us to act despite our feelings; rather, we are supposed to have changed feelings.

Biblically speaking, loving enemies means loving those who are against us.

In the present, God’s “enemy” is not someone towards whom He feel wrath. Instead, God’s enemy feels wrath against Him. Likewise, my “enemy” is not necessarily someone towards whom I feel wrath. Instead, my enemy has wrath against me.

[1] Rom 5:10; Phil 3:18. Also, cf. Rom 1:30; 8:7; Col 1:21.

[2] N. T. Wright, “Romans,” p. 520; cf. Colin Kruse, Romans, p. 237.

[3] After all, a person might respond back with hatred, but this is not necessary for them to be counted as enemies.