We need to re-enchant the world.

I’ve said it. You’ve said it. Even some of our naturalistic, non-theistic friends have said it.

Once upon a time Gods and heroes walked the Earth. People encountered dragons and faeries often enough that no one would think of questioning their existence. Most importantly, magic was a part of everyday life. The world was enchanted.

But not anymore.

We know the causes. Monotheism and its erasure of the many Gods and our ancestral religions. The corruption of the Christian church and the rise of Protestantism and its obsession with the written word. The industrial revolution and our disconnection from the land. The backlash of scientism against those who ignorantly reject legitimate science. All of that and more has driven enchantment from our contemporary world.

But what if that’s a lie? What if the world not only isn’t disenchanted, it’s never been disenchanted?

A new book

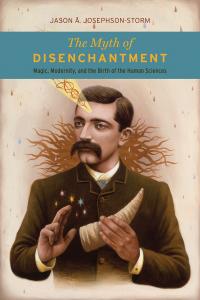

That’s the premise of The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity and the Birth of the Human Sciences by Jason Josephson-Storm, Professor of Religion at Williams College in Massachusetts. The book is as much a work of history as it is religious studies. Josephson-Storm spends over 300 pages showing how many of the very people we consider the fathers of the enlightenment were themselves involved with magic and the supernatural. Giordano Bruno is one good example, but so are more widely known figures such as Rene Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton.

That’s the premise of The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity and the Birth of the Human Sciences by Jason Josephson-Storm, Professor of Religion at Williams College in Massachusetts. The book is as much a work of history as it is religious studies. Josephson-Storm spends over 300 pages showing how many of the very people we consider the fathers of the enlightenment were themselves involved with magic and the supernatural. Giordano Bruno is one good example, but so are more widely known figures such as Rene Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton.

Josephson-Storm says:

That the heroes of the “age of reason” were magicians, alchemists, and mystics is an embarrassment to proponents and critics of modernity alike.

Disenchantment may seem like a modern phenomenon, but people have been talking about it for a very long time. One of Chaucer’s 14th century poems complains that once “all was this land fulfild of fayerye” but “now kan no man se none elves mo.” Yet as Josephson-Storm points out, “Britons would not only talk of fairies for the next six hundred years, but they would also repeatedly describe different variations on the departure of the fairies.”

Sigmund Freud “argued that religion is essentially superstition, embedded in infantile fantasy and anthropological fallacy.” And yet in letters to friends

he could be found recounting various anecdotes about ghosts and visions, clairvoyance and precognition. Among close friends, Freud could share his fascination with the occult, suggesting that it contained some truth.

Marie and Pierre Curie participated in seances. In a letter to a friend, Pierre said “These phenomena really exist and it is no longer possible for me to doubt them. It is impossible but it is so; and it is impossible to deny it after the sessions, which we performed under perfectly controlled conditions.”

Josephson-Storm concludes:

Disenchantment is a myth. The majority of people in the heartland of disenchantment believe in magic or spirits today, and it appears that they did so at the high point of modernity. Education does not directly result in disenchantment.

And this is true in “Godless” Europe as well as in “Christian” America. Josephson-Storm quotes surveys that show “despite radically different percentages of people who believe in God … Americans and Britons have similar paranormal beliefs.”

Why does the myth of disenchantment exist?

So why do we think we have disenchantment? Josephson-Storm places the blame mostly on colonization and ethnocentrism. As the European powers began to conquer the nations of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, they looked for moral justification for what was clearly an abuse of power. As the Romans had done with the native Britons, they called them “savage” and “in need of civilization”. They called their animistic religions “primitive” and “superstition”.

Josephson-Storm explains that the original meaning of “superstition” wasn’t belief in magic, but belief in the wrong kind of magic. It was believing humans could do what proper Europeans thought could only be done by their God, or by demons. Superstition meant unapproved beliefs.

The usage has changed in our society, but the core meaning has not.

This rationalization was formalized in the Doctrine of Discovery, the idea that all land belonged to the first Christian nation to “discover” it, regardless of who was already living there. It began with a papal bull in 1455 and was codified into American law in the 1823 Supreme Court decision Johnson v. M’Intosh.

Disenchantment also allowed Europeans to distance themselves from the ugly parts of their own past. Bruno was burned at the stake in 1600, Galileo was forced to recant heliocentrism in 1633, and the Salem witch trials and executions took place in 1692. This continues today with those who want nothing to do with any religion because of those who use it to justify their own hatred and murder.

Today’s “proper” society is secular. Religion may be a nice affectation, but its only power is presumed to come from either psychological factors or from political action. Take your religion seriously and you’re likely to be mocked, even inside your own tradition.

And still, many of our most educated and sophisticated friends and neighbors will privately discuss mystical experiences, magical practices, and religious beliefs, even as they publicly ignore them or rationalize them away.

The Emperor has no clothes

Disenchantment is a myth – a story we tell ourselves to help us understand the world and our place in it. But the Emperor of Disenchantment is naked, even as those of us who live in a magical universe keep talking about how thick his armor is.

So as committed Pagans, polytheists, and magicians of all varieties, our job is not to re-enchant the world. Rather, our job is to maintain our commitment to the enchanted lives we already have, and to help those who are willing to break away from mainstream assumptions to see the enchantment in their own lives.

This is a book review, but mainly it’s a call to action based off a book. If you agree with the premises of this essay you probably don’t need to read The Myth of Disenchantment. If you want to see the evidence for yourself, Josephson-Storm does an very good job of organizing and presenting it. It’s a work of scholarly history: its emphasis is on presenting the facts, not on telling a compelling story.

For those who care about such things, I bought my copy of The Myth of Disenchantment.

The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity and the Birth of the Human Sciences

by Jason Josephson-Storm

published by the University of Chicago Press – May 2017

400 pages

trade paperback: $32.00, kindle: $17.60