Immigration is never far from the news. Here in the United States Trump’s demonization of immigrants and his wall fetish (combined with Congress’s continuous refusal to address immigration realities across multiple administrations) means we never stop hearing about it. There are millions of refugees from the wars in the Middle East in Europe and other places.

And then there are the individual cases I read about on Facebook: friends from around the world who are trying to move to the United States, and Americans who are trying to move to Europe. Some have been successful and some have not.

When I was in Ireland back in March, we visited EPIC – the Irish Emigration Museum. You’ll notice that’s spelled with an “E” not an “I”. That’s not Irish spelling vs. American spelling – those are two different words. “Immigration” means to move in – “emigration” means to move out. The two always balance. Everyone person who moves into a new country also leaves an old country.

I had a powerful experience in the EPIC Museum. It was very different from my experiences at Fourknocks and Lough Gur, but it was just as powerful in its own way. I’ve struggled with writing about it, in part because my experience was and is complicated, even though there’s nothing Otherworldly about it. But also because it doesn’t lend itself to my usual narrative storytelling and teaching.

But I need to write about this, one way or another.

This was the first exhibit that grabbed my attention. It shows the many ways people have come to – and left – Ireland over the centuries, from tiny boats to sailing ships to ocean liners to jet liners. The story of humanity is the story of migration.

Anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics all tell the same story. Our species began in East Africa. We were not the first human species, but we are currently the only one. About 70,000 years ago a small group of modern humans left Africa and began to move east. Every person alive today not of sub-Saharan African ancestry is their descendant. Within 20,000 years they had reached Australia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Some of them would continue going east and eventually populate the Americas, while others went west and north and became the many European tribes.

Though many of us like to put down roots, ultimately we are a wandering species. Sometimes our migrations are voluntary. Other times they are coerced. I think of my own cross-country moves: from Tennessee to Indiana, from Indiana to Georgia, and from Georgia to Texas. I didn’t want to leave Tennessee and I didn’t want to leave Georgia, but in both cases my job went away and I had to go where I could find another one. I had high hopes when I moved to Indiana, but it turned out to be a bad job working with some bad people – I had to leave.

Though many of us like to put down roots, ultimately we are a wandering species. Sometimes our migrations are voluntary. Other times they are coerced. I think of my own cross-country moves: from Tennessee to Indiana, from Indiana to Georgia, and from Georgia to Texas. I didn’t want to leave Tennessee and I didn’t want to leave Georgia, but in both cases my job went away and I had to go where I could find another one. I had high hopes when I moved to Indiana, but it turned out to be a bad job working with some bad people – I had to leave.

The interpretive sign on this column says

Hunger, Work, and Community

We emigrate because we cannot stay, because we want to go, or a mixture of both. Three elements are strong in the Irish story of emigration: Hunger, Work and Community …

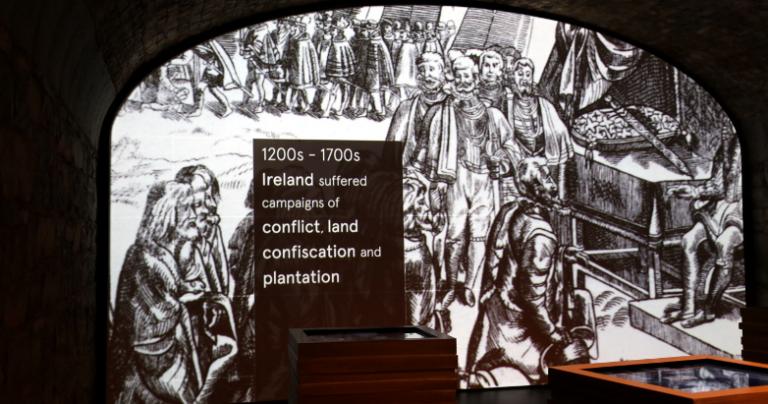

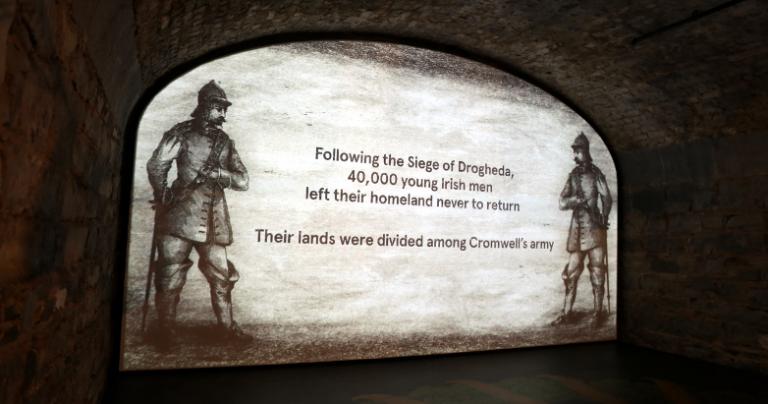

The Irish Potato Famine is well known. What is not well known outside of Ireland is that the Great Famine was far from the first time large numbers of Irish people were forced to leave their homes.

The same Normans who invaded England in 1066 (a date we all learn in school) also invaded Ireland in 1169. We never hear about that here in the US. Ireland would not be independent again until 1922, and to this day Ulster remains under British control.

It can be argued that by the 15th century, Ireland was no different from other European lands, where ordinary people were ruled by nobility with whom they had little in common. But to whatever extent that might have been true, it ended when Henry VIII attempted to force the Irish to abandon Catholicism for his new Church of England. This situation got far worse under Cromwell and his Penal Laws, which essentially stripped citizenship from Catholics. Say what you will about the Catholic church (and there is much to say) but imagine being unable to hold office, practice law, inherit property, have your marriages recognized or your births recorded because you refused to change your religion.

The last of the Penal Laws were not repealed until 1920.

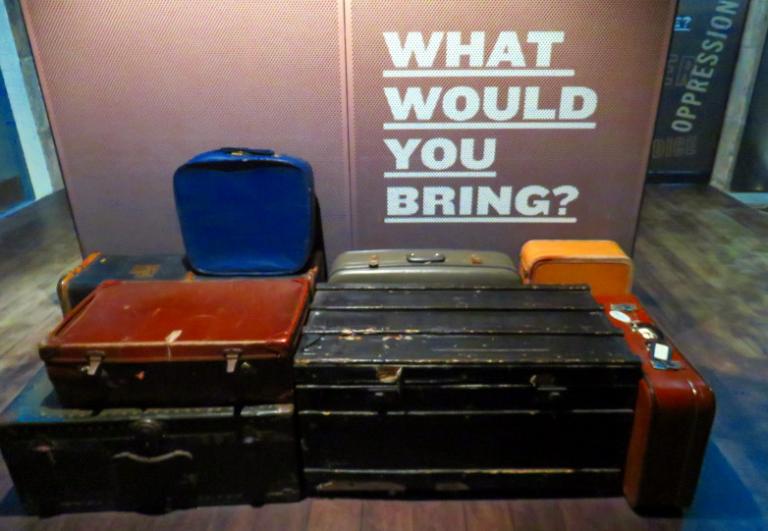

When I went away to college I packed everything I needed into my 1971 Ford Maverick. By the time Cathy and I moved from Georgia to Texas, we needed a professional moving company with a 48-foot trailer. We bought our bedroom furniture in Tennessee, our dining room furniture in Indiana, and our kitchen table in Georgia. It’s all here with us in Texas.

The Irish people who were able to book passage to North America to escape the famine were limited to what they could carry with them. The same is true of most of those fleeing war zones today.

What would you bring with you, if all you could carry was one suitcase?

If you have to leave, you leave. But if you leave you need some place to go. Emigration and immigration always balance. Where could you go, if you needed to leave your homeland?

For our early human ancestors, this was no problem. Just go a little further down the coast, a little further inland. The world was big and new, with plenty of natural challenges but completely open for humans to fill.

Except it wasn’t. We are currently the only human species, but we weren’t the first. Most of the world was uninhabited by any humans, but we know we ran into Neanderthals, because those of us of European descent carry a small amount of their DNA. But we’re here and they’re not. Did we kill them off? Did we simply outbreed them? It’s likely we’ll never know.

Last July I posted a series that retold the story of the Irish God Lugh. The third entry was titled The Leadership of Lugh – A Response To Oppression. It’s the story of how Lugh led the Tuatha De Danann to victory over the Fomorians, who were oppressing them. I was genuinely surprised when a few people called the story “settler colonialism.”

Perhaps it is, though I read the story in the context of current events, where immigrants are oppressed and where those in power are killing people for failing to show deference to them. Still, when lower-tech cultures collide with higher-tech cultures, it never ends well for the lower-tech folks. I hope readers are sophisticated enough to tell the difference between invading armies and hungry refugees.

And the question remains: where could you go, if you needed to leave your homeland?

Where can people go who must emigrate? Where can people go who are fleeing war, famine, religious or cultural oppression, or poverty?

There are still plenty of open spaces in the world, especially in the Americas. But there are no unclaimed spaces. Every square inch of this world is surrounded by a virtual wall, with gatekeepers to decide who can come in and who must stay out. And mostly, they keep people out.

I have two college degrees, in-demand skills, and I’m in good health. But I’m at the age where a quick internet search turned up no countries that will take me as an immigrant. I suppose if things got bad enough that I was a legitimate refugee Canada or Ireland or New Zealand would show some compassion, but I can’t count on that. In any case, I’m stubborn enough to stay here no matter how bad it gets. Or so I like to think.

To be clear, I do not expect the United States will ever become so regressive I’ll need to leave. Then again, millions of Jewish people in 1930s Germany thought the same thing.

Where could I go if I needed to leave?

Where could you go if you needed to leave?

The later sections of the EPIC Museum have a more pleasant feel to them. They highlight Ireland’s successes in the 20th and 21st centuries, and how Irish culture and identity are strong across the world, especially in areas where Irish immigrants settled.

I know I have some Irish ancestry, though exactly how much is uncertain. I walked out of the EPIC Museum with the realization that because they left as emigrants, I could return as a pilgrim, albeit an American pilgrim. My family has been in this country for at least 220 years and despite my Irish heritage, my connections to the land and people of Ireland, and my worship of Irish Gods, I am an American.

My Irish ancestors had to leave, and they came here.

Where could you go if you had to leave?