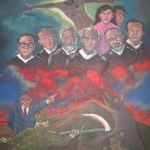

25 years ago, on November 16, 1989, six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter were brutally murdered by a US-trained Salvadoran death squad at the Universidad de Centroamerica in San Salvador. It was one of the lowest points in the shameful story of the US-orchestrated Central American civil wars of the 1980’s. This incident triggered an ongoing protest movement led by American priest Father Roy Bourgeois to close the School of the Americas in Ft. Benning, Georgia, where some of the most brutal Latin American terrorists were trained as part of the tragic US Cold War strategy. What had these priests done to be assassinated so brutally? They were promoting a liberation theology which offered genuinely good news to the marginalized and spoke offensively prophetic truth to the powers and principalities who oppressed them.

25 years ago, on November 16, 1989, six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter were brutally murdered by a US-trained Salvadoran death squad at the Universidad de Centroamerica in San Salvador. It was one of the lowest points in the shameful story of the US-orchestrated Central American civil wars of the 1980’s. This incident triggered an ongoing protest movement led by American priest Father Roy Bourgeois to close the School of the Americas in Ft. Benning, Georgia, where some of the most brutal Latin American terrorists were trained as part of the tragic US Cold War strategy. What had these priests done to be assassinated so brutally? They were promoting a liberation theology which offered genuinely good news to the marginalized and spoke offensively prophetic truth to the powers and principalities who oppressed them.

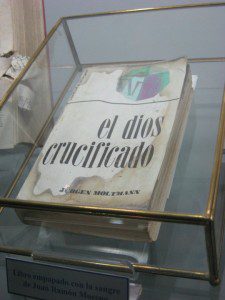

I went to the site of the Jesuits’ murder in 2010 on a seminary trip. Their former rectory has been turned into a museum in which shredded articles of their clothing and their blood-spattered, bullet-torn books are kept on display in glass cases. The graphic that I use for my blog site is a cropped photo of an Italian-English dictionary that was riddled with machine gun bullets there. One of the most haunting items in the collection was a Spanish language trans lation of Jurgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God. There’s something very appropriate about a book stained by martyrs’ blood that describes Jesus’ crucifixion as something that happened to God. The title may seem offensive to some Christians, because Jesus got crucified, not God. Duh!

lation of Jurgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God. There’s something very appropriate about a book stained by martyrs’ blood that describes Jesus’ crucifixion as something that happened to God. The title may seem offensive to some Christians, because Jesus got crucified, not God. Duh!

Except that Jesus is God. And there’s a side to his crucifixion that has been completely neglected for most of the history of its interpretation in the European church. Jesus didn’t just die to pay for our sins; Jesus died to show solidarity with the victims of sin, showing unequivocally that God takes their side against their oppressors. It makes sense that in the many centuries after Roman Emperor Constantine ended the persecution of Christians and fused empire and church into a single entity called Christendom, there could be no comprehension of the cross’s solidarity with the marginalized. When theology is developed for centuries from the perspective of the privileged, it’s very easy to forget that sin actually has victims. Sin comes to be understood as a solipsistic question of rule-breaking between each of us as individuals and God.

But sin does have victims. All of our idolatry and greed and gluttony fuel a demonic socioeconomic order that crushes the poor, usually in countries across the world far out of sight and mind of the privileged. One of the Jesuit martyrs, Ignacio Ellacuria, coined the phrase pueblo crucificado (crucified community) to describe the most vulnerable victims of our world’s collective sin in an essay written in 1977. Ellacuria claims that the pueblo crucificado are the people who continue the saving work of Jesus’ cross through their own crucifixion by the sin of the world. How does their suffering produce salvation? Ellacuria writes, “The crucified community is a judge in its mere existence, without dictating sentence, and its judgment is salvific because it unmasks the sin of the world.”

Before you get in a tizzy about this claim, let me share that I have experienced the salvation of which Ignacio Ellacuria speaks firsthand. And it actually has a solid Biblical foundation in the first Christian sermon that was ever preached in Acts 2. The climax of Peter’s sermon in the Jerusalem temple is a line in verse 36 where he says, “Therefore let the entire house of Israel know with certainty that God has made him both Lord and Messiah, this Jesus whom you crucified.” The next verse says about the crowd who were listening to Peter: “Now when they heard this, they were cut to the heart and said to Peter and to the other apostles, ‘Brothers, what should we do?'” Peter tells them to repent and be baptized in the name of Jesus so their sins can be forgiven, and 3000 get baptized that day.

Peter says nothing in his sermon about heaven or hell. Nor does he say anything about Jesus’ death providing atonement for sin in the way that animal sacrifices provided atonement under Jewish sacrificial law. He doesn’t say anything that resembles the “gospel” according to the Romans Road formula of salvation. What he says to the crowd is very simple and straightforward: you killed your messiah. And the crowd is saved by being cut to the heart with conviction at Peter’s words. They are saved by being judged with the monstrosity of their sin when this judgment shatters their self-assurance and forces them to their knees “so that [their] sins may be forgiven; and [they] will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit.”

Now here’s the problem in our day. It’s very hard to be cut to the heart by Jesus’ cross anymore. There are too many layers of abstract theology draped over it. We sing cheery, major key songs in church about getting washed in the blood of the lamb without ever pausing to reflect on the physical pain involved in the shedding of Jesus’ blood. We are not directly implicated in the murder of our people’s messiah like the Jews who were listening to Peter in the Jerusalem temple 2000 years ago. So we think “salvation” is about getting God the Father off our case for breaking his rules by saying a special prayer or reciting a catechism or performing another speech-act that shows we have “accepted Jesus as our personal Lord and Savior.”

But I’m not sure you can be really saved unless you are cut to the heart. At least I wasn’t saved until I was cut to the heart. I got baptized when I was 8. I rededicated my life to Christ at a Young Life camp at age 16. But I didn’t get saved from my slavery to the dehumanizing forces of our world’s sin until an August afternoon in San Cristobal de las Casas, Mexico in 1998. I had gone to San Cristobal like dozens of other gringo hippies in search of the Zapatistas, the sexiest revolutionary movement that had happened since the Sandinistas in the 80’s. When I got to San Cristobal, I discovered that it had become a Zapaturismo trap, filled with stores selling Zapatista t-shirts and ski masks to ignorant twenty-year old gringos like me. I remember watching in disgust as several very loudly American frat-boys high-fived each other for a photo with their Zapatista merchandise.

As I was standing in the Zocalo city square feeling like an idiot, a little girl approached me with Zapatista dolls that she was selling for a dime apiece. She was about five years old. She was barefoot. She was wearing one of the blouses of the Tzeltal Mayan people who lived in surrounding villages. She said, “Compralo! Por favor señor, compralo!” (Buy it, please sir, buy it). She started pulling on my hand because I didn’t respond quickly enough. In that moment, I was cut to the heart. God told me, “You can never be a tourist again.” At least that’s what I wrote in my journal that night. I was called out by her poverty, which was impossible for me to do anything about. Jesus saved me through that little girl in many subsequent years of reflection and decision-making that were haunted by that heart-cutting moment. She compelled me to go all in for the kingdom of God. I understand salvation to happen when we stop living according to the world’s scripts and rules and give our lives to the kingdom.

Ellacuria writes that the pueblo crucificado doesn’t refer to a clearly defined set of people in terms of class or race or political orientation. It is rather the term for whoever Jesus is talking about in Matthew 25 as the hungry, the naked, the sick, the strangers, the imprisoned, because Jesus says, “Whatever you do to them, you do to me” in the last parable he told in Matthew before showing on his cross what we do to him every time we crush the marginalized. The pueblo crucificado refers to those whose victimhood at the hand of our world’s collective sin can call us out and cut our hearts so that we abandon the world and give our lives to God’s kingdom.

The original word for church in Greek is ekklesia. It is usually translated as “gathering,” but this sweeps past an important linguistic quality about this compound word, which is literally the “out-calling” (ek + klesia). When Jesus told his disciples to “take up their crosses and follow him,” the word “cross” did not have the spiritualized meaning that it does today. It was simply a very heavy plank of wood that condemned prisoners carried on their shoulders in their procession out of the city gates to be crucified. A call to take up your cross would have meant taking your place in this procession of condemned prisoners, having completely renounced your worldly status and dignity. That’s why I would define the true church as those who have been “called out” of the world to walk with the pueblo crucificado.

Contemporary theologian Scot McKnight stirred up some conversation recently by saying in his new book that the kingdom of God must have the church at its center and that young “skinny jeans” activists who don’t go to church can’t claim to be doing kingdom work simply by engaging in “social justice.” I agree with what he’s saying in this sense. We cannot avoid being corrupted by the world’s idolatrous systems without structuring our lives according to the countercultural liturgy that Christian worship is supposed to instill in us. The liturgy of Christian worship should be the core of our resistance. Based on what I’ve witnessed in the 17 years since I got saved by the Mayan girl, social justice activism that doesn’t have deep spiritual roots leads to exhaustion, sectarian infighting, and ultimately selling out.

But I would offer a corollary claim to Scot McKnight’s statement: a church cannot claim to be the true church, in the sense of being genuinely “called out” of the world, unless it is walking in solidarity with the pueblo crucificado. Or in the words of liberation theologian Jon Sobrino: “Apart from the poor, there is no salvation.” If the Christian community that gathers to worship simply produces the exact same suburban lifestyle that gets created among the families who build their Sundays around travel soccer games instead, then ekklesia hasn’t really happened. It doesn’t matter whether communion happens every Sunday, whether the liturgy happens exactly the way St. John Chrysostom wrote it down, or even if the pastor manages to preach a sermon consisting entirely in words from scripture. Church only happens insofar as people are called out of the world and into solidarity with the crucified. This life of solidarity with the messiah who never stops being rejected, co-opted, and exploited by his own people is what I would call the kingdom of God.