You might be thinking the answer is obvious: Japan is not a Christian country (less than 1% of Japanese claim Christian faith). But it’s a little more complex than that. The fact is, Japan does celebrate quite a few festivals that are associated with Christianity – in its own, Japanised way. In fact, the Christian elements of these festivals usually aren’t transmitted when celebrated in Japan, leaving just the secular (and often, Pagan) symbols behind, alongside some unique innovations by the Japanese. Some of these festivals include:

Christmas (Kurisumasu)

Although perhaps the most important festival in much of Europe and the US, Christmas is a relatively minor event in Japan. It isn’t a public holiday for a start. It’s less of an occasion for getting together to eat with the whole family and giving gifts (although gift-giving at Christmas isn’t unknown in Japan), and more of an occasion for going out on dates or to parties. It is highly commercialised though, and around Christmas time in Japan you will see some familiar symbols like snowmen, Christmas trees and Santa Claus (or Father Christmas as we traditionally call him in the UK). What you won’t see so often are traditional Christian images like the Nativity. So in fact Christmas in Japan ends up looking more like Yule than Christmas!

Some of the new traditions that Japan has created for Christmas include the Christmas cake – a kind of sponge cake typically featuring white icing, whipped cream and strawberries – and going to eat Kentucky Fried Chicken.

The reason for the relatively low-key status of Christmas in Japan is that Shinto already has something similar – Shōgatsu, or New Year’s Day on January 1st. This involves family pilgrimages to local shrines and eating meals together, and perhaps more closely resembles the essence of Christmas in the West than Japan’s Kurisumasu.

Valentine’s Day (Barentain Dē)

This festival is perhaps the only Western festival in Japan that’s actually grown more complicated and ritual-bound than its Western counterpart. There are no references at all to St Valentine at Japan’s Barentain Dē, which is all about the giving of chocolate. But unlike Valentine’s Day in many Western countries, it is typically only women who give chocolate at Valentine’s Day in Japan. They give two particular types of chocolate gifts: Giri-choco (“obligation chocolate”) for friends and colleagues with no romantic attachments, and honmei-choco (“favoured chocolate”) for those one truly loves. But that’s not all. One month later on March 14th, Japan celebrates “White Day,” in which all the men who received chocolate at Valentine’s Day give women something in return, usually white chocolate. This is all to do with Japan’s complex culture surrounding reciprocity and gift-giving.

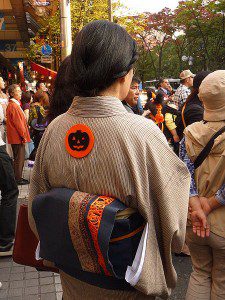

Halloween (Harowin)

Halloween seems to be getting more popular in Japan according to John Dougill’s Green Shinto blog. You’ll see plenty of pumpkins, witches, ghosts, bats, and skeletons decorating shops and public buildings in October in Japan, although activities such as costume parties and Trick-Or-Treat are rare in my experience. You’re also unlikely to see depictions of native Japanese monsters and demons, or rituals connected with the ancestors or death, because Japan has its own holidays associated with honouring departed spirits, the most important being the Bon festival in the summer.