Valheim Hof, recognised by many as the first temple to Odin, has recently opened in Denmark. And it’s beautiful. Just go and look (although beware – they did sacrifice and eat nine roosters as part of the consecration and there are pictures that some may find upsetting).

Valheim Hof is not the first contemporary Pagan temple to open, and almost certainly won’t be the last. The UK has White Spring and Glastonbury Goddess Temple for example, which are small but highly influential centres of UK Pagan worship. Then there are more ambitious projects. The Asatru Association in Iceland have plans to build their own Norse temple as well, which will apparently be 3,800-sq-ft and able to accommodate 250 people. That’s pretty impressive.

So temples are a hot topic for Pagans throughout the world, which is natural considering the popularity Paganism is enjoying at the moment. But there are differing opinions within the Pagan community when it comes to the idea of building temples. On the one hand, some love the idea of having a building where Pagans can all go to honour the deities safely and comfortably. On the other hand, there are Pagans who see their “temple” as being all around them – in the form of the forests, rivers, mountains and oceans – and so a man-made temple is not necessary.

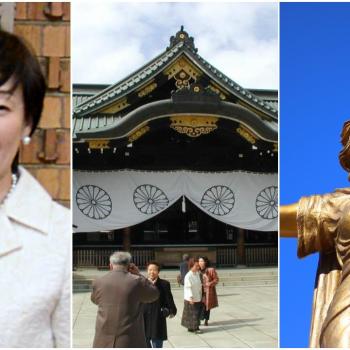

When I read these debates, I think that Shinto has a good solution. Shinto does have shrines and other man-made constructions that serve as places of worship. But compared with churches, mosques, gurdwaras and the places of worship of many other religions, Shinto shrines are for the most part quite small and low-key. Some are tiny hokora, “spirit houses” that range from the size of a bird house to the size of a small shed and are often found tucked away at the wayside or deep in forests. Then there are larger ones, jinja. These are centred around a building, traditionally constructed using only natural materials, called the honden. The honden enshrines the goshintai, a sacred object in which a kami spirit interfaces with the mortal world. Even in larger jinja, the honden tends to be fairly small and plain; moreover, it is not usually designed for ordinary people to enter. Only Shinto priests, and then only at certain times, are permitted to enter the honden.

Visitors to these kinds of shrines are instead restricted to the periphery of the honden. This may feature hokora, torii gates, a temizuya (water-basin for purifying one’s self), and places where one can make offerings. But the most important aspect of the jinja complex for me is the fact that it is out in nature. Indeed, in some jinja, there may not even be a honden – the area itself may be considered the dwelling of a kami, and therefore a honden to enshrine the kami is not necessary. What is important for visitors is interacting with and venerating the natural environment.

A good example of this is one of Japan’s largest shrine complexes, Fushimi Inari Grand Shrine – the most important shrine in Japan to Inari Ōkami. As Shinto shrines go, the honden is in fact quite large – but it is dwarfed by the enormous mountain and forest in which it is situated. If you visit Fushimi Inari Grand Shrine, you can spend about an hour or so in the main grounds surrounding the honden, but you will probably find most of your time spent climbing the mountain and walking in the forest. But even within the forest, there are continual small reminders that you are in a sacred place – stone altars, shimenawa ropes tied around trees or by waterfalls, the tunnels of red torii gates, and of course, thousands of fox statues, the guardians of Inari. But these objects never overwhelm their natural surroundings – instead, they are designed to be harmonious with the environment.

This is what I think Pagan places of worship could be like. Rather than being enormous, grand monuments of human architecture in which dozens, if not hundreds, of Pagans can gather under a roof and away from nature, I believe they could be small and understated, serving merely as an indicator and reminder of the sacred significance of a particular place without seeking to dominate it.

Having said that, I have to say I love the impressive structure of Valheim Hof. Perhaps because, being made of wood and seeming so well integrated with the natural surroundings, it actually reminds me a little of a Shinto shrine…