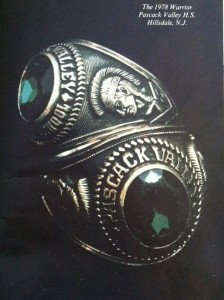

A little over a year ago, I attended my thirty-fifth high school reunion. Pascack Valley High School class of ’78. Go Indians.

A little over a year ago, I attended my thirty-fifth high school reunion. Pascack Valley High School class of ’78. Go Indians.

Seeing people you grew up with looking far older than you ever dreamed your parents could get when you were a kid is both sobering and a privilege—not all of my 401 member graduating class got to grow old.

And seeing people from your childhood and formative years connects you with your humanity, your life narrative, in ways few other things can can. Reunions are sacred space.

We gathered in a hotel ballroom. Down the hall in an adjoining ballroom was another high school reunion, a 50th. Someone mused that we should walk down and pretend we belonged—eat their food, drink their wine, act like we know them, and make everyone jealous for looking so much younger.

(Un)Fortunately we all had grown up enough not to pull off awesome pranks like this, but it did get me thinking:

One day in the not too distant future—fifteen years from now—we’ll be that class with a fiftieth reunion, and fifteen years ago, another class celebrated its fiftieth reunion, and they are now on their sixty-fifth–whoever is left.

Human existence is a cycle. An endless cycle. The more things change the more they stay the same.

And that got me thinking of the always-ready-for-a-good time book of Ecclesiastes.

What has been is what will be,

and what has been done is what will be done;

there is nothing new under the sun.

Is there a thing of which it is said,

“See, this is new”?

It has already been;

in the ages before us. (Eccl 1:9-10)

Ecclesiastes is all business with the whole cycle of life thing. Nothing is really new. It may seem that way, but you’re only fooling yourself.

Everything that is has already been and will be again. I must remember that line for my fortieth.

This lighthearted tone stayed with me the next morning. On the way home I decided to drive through some old neighborhoods and then down my old street to the house where I did most of my growing up.

My parents moved away when in 1998 and have since died. I never had a reason to go back, though I had driven by the house in recent years, whenever I was back in the area, never really having the nerve to stop.

This time, buoyed by the spirit of the class of ’78, I pulled over, got out, and knocked on the front door.

The man of the house answered. I came right out with it: Hi. You don’t know me, but I grew up here and I haven’t stood on these steps in about fifteen years.

He invited me right in. I met his wife and kids, who were somewhere between grade school and high school. They already knew who I was because my sister Angie (’77) had pulled the same stunt about a year earlier.

And it turned out they were the very people who bought the house from my parents—and they remembered them both by name. Nice touch. It felt more like home.

Their T.V. was in the same place as ours was—the room is small and has limited options. The carpet was, mercifully, different from the horrible dark, dark green shag disaster that was either on sale or in vogue when we move in in 1972. The kitchen was hardwood, the current owners having removed the carpeting my Mom (what the h-e-double hockey sticks were you thinking?) thought would work there.

My old tiny bedroom now provided solitude and safe-space for another high school student, forty years my junior. I saw the cubby my dad had built underneath the basement stairs where my dogs–Corky and Sammie–would sleep at night (we called it the “dogout”). Now it was used for storage. My dad’s workbench with its tools had become sort of a game/sewing area.

And the backyard–that great backyard. The huge oak I would climb—split into four trunks ages ago by a lightening strike—had long since died and been removed. I could see in my mind’s eye our above ground pool, but that, too, was long gone, as were the tracks in the grass from endless wiffleball tournaments. The new owner had also put up vinyl siding over the clapboard and seriously spruced up the detached garage.

The house of my youth had been transformed over the last fifteen years—but it was still “that house” I grew up in. A different family was there, with its own struggles and triumphs, its own stories to tell.

But one day not terribly long ago the Enns family moved in. They were the new family, replacing the previous one, with its carpeting, TV, and bedrooms. And one day this family will move on and another will surely take its place.

Families come and go. There’s nothing really new here.

What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done; there is nothing new under the sun.

And so it goes.

It was time to go now. I may never be back again. Just like the family we replaced in 1972.

Since I wasn’t yet full of harsh reality, I decided to stop at the Dunkin Donuts a mile down the road to grab some breakfast before heading home.

I sat down to unwrap my greasy but oh so good egg bacon cheese croissant and in came a large man, in his early 30s, I’d say, proudly wearing a “River Vale Little League” coach’s, water resistant, nylon, v-neck warm-up jacket.

I played in the River Vale Little League, too, from 1970-73. I was pretty darn good, too. I played on all-star teams, and around the age of twelve I realized I could throw pretty hard. After adding a curve ball I became a legend—or so my memory tells me.

But long before and for long after my 4 brief years under the sun, others played, others threw hard, others were legends.

My coaches also wore self-identifying, territory-marking, testosterone-laced garb, though not the slick stuff they have today. Why, back in my day they had jackets with snaps and collars. But the same idea.

And I’ll bet my own son that this guy in the Dunkin Donuts was a father coaching his son—just like my coaches did. My father, as a German immigrant, never did, as it would have been an colossal disaster, but I also coached my son, from 1995—2004, from the time he was seven until he entered American Legion baseball at seventeen. Ten years. I have a closet full of warm up jackets, hats, and polo shirts. I rarely wear them.

There were coaches long before my coaches, as there will be coaches long after this young father/coach has taken his final turn. I wanted to grab him to tell him to enjoy it and to let him know what was ahead, in the years to come. But most men that age—including me—tend not to think of the cycle of life.

Is there anything of which one can say,

“Look! This is something new”?

It was here already, long ago;

it was here before our time.

This realization often comes much later, in mid-life, when the frantic pace of our youth has become tiresome, when we finally slow down a bit and take stock.

I’m just another in a long line. I’m not at the front or back. Just in the massive middle. So are you. So is everyone.

We are here for a while, busy ourselves, accomplish things, and then we move on and others continue the cycle.

I also, strangely, felt peace at the thought. I’m wasn’t exactly sure at the time why, but perhaps knowing that things are as they are and that I will not break that cycle leads to a healthy resignation, a release of the fantasy that we can control our universe, our lives.

That’s how I’d put it: my weekend was a tender “letting go” moment.

I have found that letting go is a key component of the Christian life—of any spiritual life—but I was never taught “letting go” in my Christian education, in church, college, or seminary. The sub-current always seemed to be how “special” and privileged we were to be “in,” not like the masses who don’t get it. We have our finger on the pulse of the universe. Therefore, our lives have meaning.

I was taught to think of myself as outside of the cycle.

But we live our lives within the cycle, and they have meaning. Not a meaning handed to us, but a meaning we forge—right here, right now. Not by transcending our humanity but by looking it square in the eye, shedding any notion of being above it all, getting to work, and living.

After all, as Christians believe, God himself entered the human drama, the cycle of life, as yet another man in the long line of men before and since, born of a woman, in ancient Judea, in Galilee, who grew and learned like everyone else.

God valued the cycle enough to be a part of it. So will I.