We started our “Catholic Worker Inspirations” posts last week by introducing a small sample of Peter Kropotkin. I thought we could continue to share what certain Catholic Worker Inspirations wrote on various themes – inspirations being those who inspired the Catholic Worker Movement, and in this case, those who started the movement.

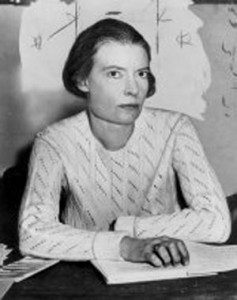

Dorothy Day, Obl.S.B., (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) co-founded the Catholic Worker with a Frenchman by the name of Peter Maurin (May 9, 1877 – May 15, 1949) in the year 1933. Day is famous for many reasons, some of which we can hope to discuss in future posts.

The Catholic Church uses the title ‘Servant of God’ for Dorothy Day in this beginning stage of her cause for canonization. She was also noted as one of four heroic, exemplary men and women – including King, Lincoln, and Merton -, role models for/of the United States, by Pope Francis during his address before the Congress of the United States (24 Sept. 2015).

In his address before Congress, Francis said: “In these times when social concerns are so important, I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints… A nation can be considered great when it defends liberty as Lincoln did, when it fosters a culture which enables people to “dream” of full rights for all their brothers and sisters, as Martin Luther King sought to do; when it strives for justice and the cause of the oppressed, as Dorothy Day did by her tireless work, the fruit of a faith which becomes dialogue and sows peace in the contemplative style of Thomas Merton.” In other words, perhaps, we’re not a great nation.

What did this exemplary woman have to say on the topic of capitalism? Not a few things.

We find it interesting that some familiar and friendly towards the Catholic Worker Movement, including one who seems to play a direct role in advancing the cause of Day’s canonization, nuance their criticism of capitalism, or simply hesitate to say that the Church, or our “Catholic Worker Inspirations”, would reject capitalism, as such.

There seems to be little room to interpret the Servant of God Dorothy Day as having held a nuanced, gentle critique of this system, as if she would not wholly reject it. This is similar to what contemporary defenders of capitalism have to say when figures like John Paul II, Benedict XVI, or Francis fail to embrace capitalism. Instead, we’re told, these figures detest or critique this or that aspect of capitalism, or a capitalism that is operated by greedy folk. In an up-to-date example, we show how this attitude and allegiance to capitalism is unfounded.

Pardon the distraction. Dorothy Day was consistent in her position against capitalism. Before we share some of what Day said/wrote, I’ll have you note the years in which these quotes come from – namely, after she converted to Catholicism.

1930s

Marxist Communism has been condemned by Catholics for its destruction of family life. What then of capitalism, which creates an ever-growing proletariat ground down to such a level of insecurity and misery that decent family life is almost impossible? Probably we have all wondered about the dismal future of young people finishing school these days, with years of sterile learning behind them and no prospects of a job ahead. There are countless thousands of them well on in their twenties today who have never had a job and whose chances decrease as the years pass. Capitalism bars them from living by the fruits of the labor they would willingly give, and marriage is out of the question. Even if they have jobs, Catholic young people dare not assume the responsibilities of marriage because they “can’t afford a baby.” – The Catholic Worker, January 1936.

1940s

The bourgeois, the materialist, fights for abstractions like freedom, democracy because he has the material things of this life. (Which he is most fearful of being deprived of.) The poor fight for bread, for increase in wages, for time to rest, for warmth, for privacy, these things are holy. – The Catholic Worker, June 1944.

Truly, Day, friendly towards the Distributism of Gilbert Keith (G.K.) Chesterton and others, cites Chesterton and connects this to their detestation of capitalism.

One of the saddest things about this whole controversy is that our opponents look upon agrarianism as visionary. Here is what Chesterton said about such a criticism:

“They say it (the peasant society) is Utopian, and they are right. They say it is idealistic, and they are right. They say it is quixotic, and they are right. It deserves every name that will indicate how completely they have driven justice out of the world; every name that measure how remote from them and their sort is the standard of honorable living; every name that will emphasize and repeat the fact that property and liberty are sundered from them and theirs, by an abyss between heaven and hell.”

This sounds pretty harsh from the gentle Chesterton, but we, who witness the thousands of refugees from our ruthless industrialism, year after year, the homeless, the hungry, the crippled, the maimed, and see the lack of sympathy and understanding, the lack of Christian charity accorded them (to most they represent the loafers and the bums, and our critics shrink in horror to hear them compared to Christ, as our Lord Himself compared them) to us, I say, who daily suffer the ugly reality of industrial capitalism and its fruits–these words of Chesterton ring strong. – The Catholic Worker, December 1948.