My dearest friends,

The Catholic Worker Movement finds its strength and authority not the the Church as a mere institution or in the writings of theologians and philosophers for the sake of intellectual justification, but roots its power in its concrete love of God and love of neighbor. This love materializes in direct and humble openness to the poor, where service and community manifest God’s saving mercy. Here the Gospel can be found.

We have started to examine the inspirations of the Catholic Worker Movement when we introduced Peter Kropotkin and Dorothy Day some days ago.

If you’re interested in joining us in this long investigation and discovery of Catholic Worker Inspirations, all of the posts will be categorized under “Catholic Worker Inspirations“. Maybe I’ll be able to get a Category or Series tab somewhere for easier access.

Pardon the housekeeping.

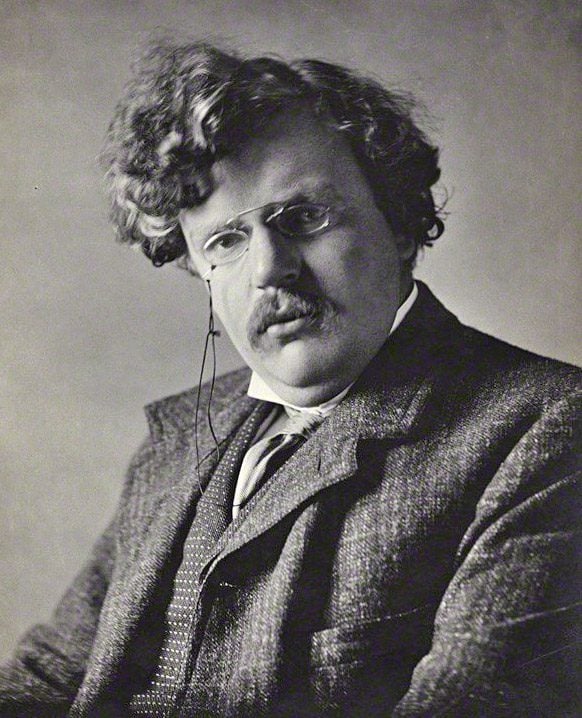

Gilbert Keith (G. K.) Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was a husband and a father, and a convert to Catholicism. Chesterton was a journalist and wrote poetry, biographies, theology, and philosophy, and much more.

Before starting Ritalin, Chesterton was one of the first few authors I read. I think I read eight books (front to back, or almost front to back) before Ritalin.

Anyways, I read Chesterton’s Saint Francis of Assisi (1923) some years ago before taking a seminar on the writings of Saint Bonaventure.

We can discuss at another time the legacy of Saint Francis, his role in Chesterton’s conversion, and how this all works into inspiring the Catholic Worker Movement.

For now, let’s turn to what Chesterton had to say about Capitalism and how it relates to the United States and the Catholic Worker Movement.

Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin both drew heavily from Chesterton and others on matters of social and economic organization. Day would recommend four texts as an introduction to the model of societal structuring they embraced called ‘Distributism’, and two of those were by Chesterton (the other two by Hilaire Belloc). She recommended Chesterton’s What’s Wrong With the World and The Outline of Sanity.

Distributism, some would say, came out of a desire to concretely apply the principles and teachings of the Catholic Church with Leo XII’s Rerum Novarum (1891) serving as foundational.

Capitalism was clearly not working out and totalitarian, atheistic socialism proved no better.

Capitalism, like a totalitarian form of socialism, would ultimately deprive man of his dignity.

Of course, one could get a taste of capitalism in England, but we’ll draw from Chesterton’s summary, What I saw in America (1922), plainly, written after visiting the United States.

Concerning capitalism, Chesterton wrote,

Capitalism was not a normalcy but an abnormalcy. Property is normal, and is more normal in proportion as it is universal. Slavery may be normal and even natural, in the sense that a bad habit may be second nature. But Capitalism was never anything so human as a habit; we may say it was never anything so good as a bad habit. It was never a custom; for men never grew accustomed to it. It was never even conservative; for before it was even created wise men had realised that it could not be conserved. It was from the first a problem; and those who will not even admit the Capitalist problem deserve to get the Bolshevist solution. All things considered, I cannot say anything worse of them than that.

Capitalism is not value-free. It isn’t a mere tool, but has its own mechanisms and preferences, built by certain (vicious) ambitions and, clearly, reinforcing them along the way. We must work towards an economy that is beyond capitalism because, as Chesterton says, it is clearly destructive …

A wise man’s attitude towards industrial capitalism will be very like Lincoln’s attitude towards slavery. That is, he will manage to endure capitalism; but he will not endure a defence of capitalism.

The way the working class is treated in capitalism – alienated, exploited, commodified, etc. – demonstrates its instability:

…the one great truth to be taught to the middle classes was that Capitalism was itself a crisis, and a passing crisis; that it was not so much that it was breaking down as that it had never really stood up. Slaveries could last, and peasantries could last; but wage-earning communities could hardly even live, and were already dying.

We must not see the effects of capitalism in a vacuum – we’ll tend to objectify the life and dignity of workers if we do. Workers have it hard, but they’re not just workers. They are people. Many people -used to- get married and start families. Capitalism, Chesterton would write, destroys families.

In Chesterton’s The Well and the Shadows (1935), found in Vol. III of the Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton, this point is further discussed:

It cannot be too often repeated that what destroyed the Family in the modern world was Capitalism. No doubt it might have been Communism, if Communism had ever had a chance, outside that semi-Mongolian wilderness where it actually flourishes. But, so far as we are concerned, what has broken up households and encouraged divorces, and treated the old domestic virtues with more and more open contempt, is the epoch and Power of Capitalism. It is Capitalism that has forced a moral feud and a commercial competition between the sexes; that has destroyed the influence of the parent in favour of the influence of the employer; that has driven men from their homes to look for jobs; that has forced them to live near their factories or their firms instead of near their families; and, above all, that has encouraged, for commercial reasons, a parade of publicity and garish novelty, which is in its nature the death of all that was called dignity and modesty by our mothers and fathers.

We can see what we so often miss in contemporary discussions concerning capitalism. There is a value – rather, vice – system that is part of this structure of organizing life. Entrepreneurship, ownership, creativity, etc., isn’t exclusive to capitalism. But when we add vices like materialism, individualism, utilitarianism, consumerism, relativism, atheism, etc., we start to see the prevailing economic order for what it distinctly is.

Chesterton, then, doesn’t merely want to bash on Capitalism because it is a worthy target, he wants to join in the cause for a more just order. His aim has a greater focus on returning to the land, on embracing a simple agrarianism of old. Is it utopian to think we can have honest labors, simple living, and a renewed spiritual connection with creation and the Creator?

In 1948, Dorothy Day quotes Chesterton‘s response to such an objection:

They say it (the peasant society) is Utopian, and they are right. They say it is idealistic, and they are right. They say it is quixotic, and they are right. It deserves every name that will indicate how completely they have driven justice out of the world; every name that measure how remote from them and their sort is the standard of honorable living; every name that will emphasize and repeat the fact that property and liberty are sundered from them and theirs, by an abyss between heaven and hell.

The Servant of God, Dorothy Day adds to this:

This sounds pretty harsh from the gentle Chesterton, but we, who witness the thousands of refugees from our ruthless industrialism, year after year, the homeless, the hungry, the crippled, the maimed, and see the lack of sympathy and understanding, the lack of Christian charity accorded them (to most they represent the loafers and the bums, and our critics shrink in horror to hear them compared to Christ, as our Lord Himself compared them) to us, I say, who daily suffer the ugly reality of industrial capitalism and its fruits–these words of Chesterton ring strong.

Capitalism leads to an unjust accumulation of wealth and to the denial of each family’s right to property. This is why Chesterton, signaling what Distributism aims for, says, “The problem with capitalism is not too many capitalists, but not enough capitalists.”

We need a system that allows for more people to own property, not a system of few property owners, which closes doors and absorbs the surplus value of goods at the expense of labor, denying any chance to eventually own their proper means of production.

We’ll continue our discussion on Chesterton, Distributism, and the Catholic Worker Inspirations another time.

Until next time,

If you have found the content on Keith Michael Estrada’s “Proper Nomenclature” to be useful, kindly consider supporting the cause with a donation.

Use the button below to donate through PayPal:![]()

Thank you!

p.s. As always, let me know who you would like to discuss related to the Catholic Worker Movement in the comment box below or by contacting me.