I’m not so much interested in the return on my money, as I am in the return of my money. Will Rogers

I’ve spent quite a bit of time lately, trying to figure out our family finances going forward.

I have an advanced degree in management, with graduate level courses in finance and accounting under my belt. I’ve even taught graduate level courses in management at one of our local universities.

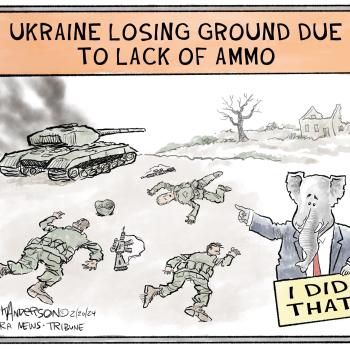

That does not mean that I have a crystal ball about what the markets are going to do in the next decade. In fact, about all it means in real life is that I understand things like beta and r squared and other odd whatnots of data that the investment firms put out there. Truth told, my insight into politics has actually proven to be a better predictor of long term financial trends than technical financial data.

The markets have given us quite a hayride since the turn of the century. We’ve had two big recessions that basically leveled the returns generated in the bull runs that came after each of them. Extreme volatility has been the hallmark of the markets in the first years of the 21st Century.

I kind of knew this was going to happen way back, but not because of my master’s level coursework in finance and accounting. I knew because I understand politics and I saw what most people don’t want to admit: We are electing ideologue puppets who do not care about this country and who have put corporatists in charge of our nation.

So, what does this mean to the retiring baby boomer generation? Just this: You’d better be careful.

As I said, I’ve spent a bit of time lately, re-jiggering our itty bitty retirement savings. That led me to read the info on various investment web sites. One thing that struck me is the paucity of honest advice from the financial services industry for people who are actually in retirement.

Most of what’s out there is a series of useless three, four or five question risk assessment questionnaires that end in a pretty little round chart advising you to put your doh re me into set percentages of equities, bonds and maybe the side bet du jour, such as REITS or commodities. There’s usually a breakdown between percentages of international and domestic investments, but that’s about it.

I’m not arguing that the allocations you choose between equities (read that growth and loss) and bonds (read that income) will pretty much determine how your investments ride the market. In fact, I’ll go a step further and say that almost everything you’re doing with your investments is just riding the market.

If what you are doing when you invest is riding the market, and the percentages you chose between growth (and loss) and income determine how your investment boat floats, then that makes those ridiculous questionnaires and their pie charts important. What’s scary about this is that the percentages those charts are advising are totally off for retirees. They are far too risky, and they are based on a laughably fallacious assumption.

These savings, which are often accrued with a self discipline and self denial about money that approaches a fashion model’s discipline concerning food, may well be their owners’ best shot at all the extras and a lot of the necessities of their elder years. Without Social Security, these savings could be all they have between them and what people used to call “the poor farm.”

This pro forma advice, if taken down like the daily dose of castor oil that my grandmother’s generation once administered in the spring time, will probably yield you a reasonable-sized pot of money at the end of your working years. This outcome is nowhere near as certain as the investment websites imply, as those who had to retire in 2008 know. But that is another story.

At that point, you will find yourself looking at the numbers on your computer screen with the knowledge that this is all there is and you’d better not blow it if you don’t want to eat beans and rice for supper every day of your extreme old age. So, you turn to the “expert” advice on those websites and play copy cat with those little round charts and their color-coded percentages.

Sadly, your actual situation and true risk aversion probably have little or nothing to do with the proportions those charts advise. The primary reasons are a fallacious premise and human nature. Let’s take the human nature part first.

The plain truth is that all people lie to themselves about themselves like they breathe.

Those self-lies carry over into the answers you give to the three or four questions that the marketing departments of those various investment firms put out there on the internet. You will say and believe — when you are clicking answers on a questionnaire — that when the market takes a breathtaking dive for the bottom, you will not only hold your investments, you will pile more money into them. You can say that all day long when you’re answering one of those questionnaires. It won’t hurt a bit.

But the real time pain of watching your life’s savings drop, drop, drop like a rock falling into a well is something else again. Suddenly, you’re the star of a gambling movie and you’re letting your lifetime winnings ride on the next roll of the dice. Or, you’re the driver of a car who just pulled out to pass and is staring into the headlights of an on-coming semi.

The older you are, the more you have to lose, the less you can get back, and the harder staring into those headlights becomes.

People duck in those circumstances, and in the parlance of the game, “lock in their losses.”

The first rule of successful investing is “sell high.” If you can’t white-knuckle those blood-curdling dives into portfolio oblivion, you will violate that rule and sell, not only low, but historically low. You will deflate all those years of scrimping and saving and doing without with a single click of the “sell” button.

But what about the person who has no choice? What if, say, you’re actually living off those savings? What if the crumbs that are left on the table after the crash are all you’ve got? What if you have to sell to pay the bills, even if it means liquidating an unrecoverable large percentage of the fund shares you’ve labored to accumulate over the decades?

That’s the point where the advice in those little circular charts with their color-coded admonitions to buy various percentages of stock/bonds//cash/side bets become something approaching criminal. Because if you’ve done like all of us do and lied to yourself about yourself and blithely answered those questions to the gunslinger side of investing, and if you’ve then slavishly followed the advice in the little chart, you are out there with an investment portfolio whose decline you cannot stomach when it dives for the dirt.

Oh, it was great fun when said investment portfolio was soaring toward the clouds. It felt wonderful, like winning at the annual office softball game, to check your score and see the numbers ticking off in a steady climb higher. You’d check those returns and bask in your own brilliance for being such a clever investor.

But when the bitterness of going down the other side of that mountain begins to settle on you, it’s difficult not to feel panic settle on top of that. If you are actually in retirement, rather than preparing for it, that panic is not at all misplaced.

If you have, as I do, kids in college and an elderly mother to care for while you are also figuring out how to keep a roof over your own head, that panic is not only a realistic response, it may very well be an emotionally accurate assessment of your situation.

You can easily find yourself prey to the marketing advice of the disconnected minds on the other side of those little charts. They advised you to put entirely too much of your nest egg in equities for your situation and your stomach and you did it. Now you, and not they, will pay the price.

I’ve looked at the advice out there for retirees and I believe quite strongly that it is entirely too focused on growing your money instead of spending it while conserving it.

The recommendation to keep a certain portion of your retirement portfolio invested in growth and loss is — at least in the early years of retirement — good advice. But those questionnaires and resulting charts are way off in the percentages they are advising you to take. This is where we get to the fallacious assumption part.

Old-school opinion was to subtract your age from 100 and put that amount in stock. Or, conversely, to put your age in bonds and cash. Either way, the whole scenario was based on the assumption that the human life span ended at 100. It further assumed that people in retirement have less time to make up losses and a need to liquidate assets on a regular basis in order to live off them.

Today’s financial gurus quarrel with that assumption. They claim — with straight faces — that, because “people are living longer than they used to,” we should change the formula and base it on 120. Subtract your age from 120, they tell you, and put that amount in bonds. Put the rest in stock. “Keep your money working for you” by being “100% invested,” which is to say, eschew cash entirely.

All this is based on that magically altered number: 120. This new number, on which the investment industry has millions of nurses, welders, middle management types and professionals betting their retirements, is supposed to reflect the “fact” that “people are living longer” these days.

As if.

How many 120 year old grannies do you know?

The truth is, we’re not living longer. Fewer people are dying young. Our so-called longer life span is just an average that reflects the fact that stable government, better nutrition, vaccines, antibiotics and anesthesia which allows advances in surgery is giving more people the chance to live out their full span of years.

Don’t let these ludicrous claims about “people living longer” persuade you to Invest like you’re in your mid 50s and have a dozen years to work, when you’re really bumping against 70 and drawing down those savings. That’s fantasy investing. It can leave you broke and sucking air at the precise time of your life that you scrimped and saved to provide for in the first place.

In my opinion, if you need to invest percentages in growth and loss that are as high as these websites advise in order to have enough money, you are not ready to retire. You need to change something on a more fundamental level than your portfolio allocation.

Perhaps you should become a one car family, or clip the cable tv, get your books and periodicals at the library and start thinking about visits with the relatives in a nearby state instead of high dollar tours of foreign lands. Maybe it’s time to give up eating out every night and replacing automobiles, appliances and computers while they are still working perfectly well.

In addition to telling you to invest in portfolio allocations that are too risky for your age, a lot of these web sites also advise you to keep on working ad infinitum to “let your savings grow.” They use a full-blown oxymoron to describe this: “Working retirement.”

Get a part-time job they say, or maybe even a full-time job. To which I reply once again,

As if.

Are you saving in order to have money to retire, or are you saving to grow money for itself?

Do you really want to be an old coot, sacking groceries in your “working retirement?” Is that your big plan that you’ve been saving for, to work until you drop?

Whatever it takes, you need to get that growth and loss portion of your portfolio down to the point that those dives into the dirt level off and become dips in the air. You need a big chunk of your money in cash, even if it’s not earning anything, so that when the plumbing breaks or the kids need tuition or Mama has to have a hearing aid you can chin it without being forced to sell low.

And you need to pare your expenses so that these sensibly invested savings, plus Social Security and whatever pension you might have, will keep you going.

Someone should put a big red Stop! sign in front of those questionnaires and their little pie charts. Because they ask the wrong questions and they are based on fallacious premises. They give dangerous advice to vulnerable people.

They should really be asking you things like how much money will you get from other sources besides this little pot of gold you’ve saved? Do you, or will you by the time your retire, own your home? Are you saddled with short-term debt such as credit card debt and department store loans? How many miles do you put on your car each year? How healthy are you? Is your house energy efficient? What are your human liabilities: Do you have aged parents to care for, kids to educate, a disabled spouse or child?

And oh yes, what will you do when the markets tank? What is your contingency plan for the days, months, weeks and years when the whole thing craters and you are left holding a couple of quarters on the dollar of what you had before? Because it will. The only thing uncertain is when.

Sure. It has historically always come back.

In time.

But how are you gonna live while the tide is out?

The real questions, as far as risk is concerned, are (1) how much (and how long) of a dive can you take without cutting and running, and (2) how will you fare while your savings are bottom feeding? Remember: It took 10 years for the markets to come back after the crash of 1929. That’s scary stuff. But it is also a fact.

The difference now is the leveling influence of Social Security and unemployment compensation on the economy. No matter what happens, Social Security keeps pumping money into the economy. People tend to forget that, but the “earnings” of Social Security and unemployment compensation act much the same way on the economy that dividends act on stocks. They level out the troughs.

Your questions of personal survival in the choppy waters of macro trends are only partially based on the psychology that says that you and everyone else gives wonky answers on those little questionnaires. There is a bottom line here and it’s hard as concrete. How do you plan to survive and keep your obligations during those down times?

There are answers to these questions, but you won’t find them in the boring and simplistic advice being churned out by investment firms’ marketing pages. Even in retirement, investment firms are advising you to swing for the fences.

That’s bad advice. Get that growth and loss portion (stocks) down to manageable levels. Raise the income-producing portion (bonds) and non-productive but safe cash portion up accordingly.

If you’re in need of a formula, the traditional advice to keep your age in bonds and cash and put the rest in stocks is time-tested and simple.You don’t need an advanced degree to figure it out, and, unlike the advice coming from those little charts, it’s based on your reality.

Don’t worry about what-ifs like whether or not interest rates will rise. If you have cash, that’s more money for you, and if your bonds fall, they’ll keep paying themselves interest and buying more shares of themselves in the bond fund and, well, you and compounding will win out in the longer while. The trick is, don’t sell them while they’re low.

Which goes back to cash. I can’t emphasize enough that you need to keep a chunk in cash so you can live, no matter what. Assess your real-life responsibilities. Put yourself on both a short-term and a long-range budget. Ignore those questionnaires and their cutesy little pie charts. Make sure your Congressperson knows that anybody or any political party that messes up Social Security is going out the door, feet first.

Then fold up the investment planning for a year and get back to living.

All will be well.