In the book of Revelation, the apostle John sees a vision in which God speaks to the church in Sardis. It is a biting indictment:

I know your deeds; you have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead. Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die, for I have found your deeds unfinished in the sight of my God. Remember, therefore, what you have received and heard; hold it fast, and repent. But if you do not wake up, I will come like a thief, and you will not know at what time I will come to you.

–Revelation 3:1b-3 NIV

These strong words could be said of many segments of the white Christian church today. It has a reputation for being alive, but deep within there is a spiritual deadness, a spiritual slumber. And much of this is in relation to lack of repentance for sins of the past and present, sins against our African-American brothers and sisters and against our Native American brothers and sisters.

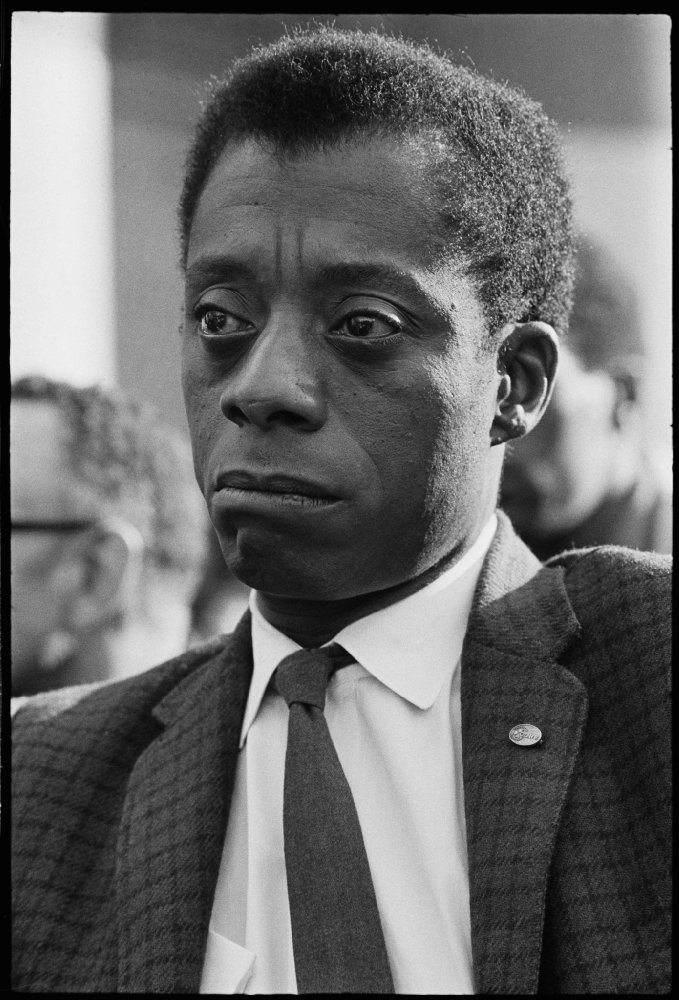

The film I Am Not Your Negro reprises the prophetic voice of Civil Rights era writer James Baldwin. The guiding thesis of the film is this: “The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. It is not a pretty story.” Director Raoul Peck layers Baldwin’s hard-hitting, convicting words for white America (narrated by Samuel L. Jackson) over the contrasting visuals of oppression against African-Americans (through slavery, Jim Crow, lynching, and other injustices) and of the white American dream in all its glitz, glamour, and inheritance. The effect is to draw our eyes to the reality that America was built and the American dream came about on the backs of the injustice done to black Americans (among other minorities). Ignoring this reality (as we usually do) not only obscures our guilt but it fails to give credit to the suffering and hard work of those who helped make America what it is. As Baldwin puts it, “I’m not an object of missionary charity. I’m one of the people who built the country.”

Throughout the film, the aim seems to be not to guilt white Americans into some sort of self-hatred, but rather to shake them awake so that they might no longer remain spiritually and morally dead. I have heard some describe the film as “hopeless.” I didn’t see it that way. I saw a great love for white Americans shining through the words of Baldwin, a longing to see them wake up, not only for the sake of their African-American brethren but for the sake of deliverance from their own moral bondage. He repeatedly emphasizes the emptiness of modern life, the pursuit of material acquisition, and the quieting of the inner moral voice. Baldwin grew up as the stepson of a black preacher, and he himself became a child preacher; while he later (sadly) abandoned his faith, the preacher’s voice of condemnation of sin seems to have remained with him. He writes, “I’m terrified of the moral apathy, the death of the heart …” in America. Can a nonbeliever be a prophetic voice? I think so.

I am terrified of the state of the American heart too. I am first of all terrified of it in myself. I am second of all terrified of it in my fellow white countrymen, who do not know what they do not know … and, as Baldwin pointed out, do not want to try to find out what they do not know. When I talk to white friends, people who I know do care about their families and their community and their God, I am baffled by their lack of willingness to engage with even one well-researched film or book or podcast that would help inform them.

I am baffled by the stubborn refusal to consider that there may be facts about black America that they do not know or understand, that they have been sheltered from, both willfully and unintentionally. (And yet, before I get too judgmental, I have to admit there are hard facts I am afraid to face too.)

I long for my white friends to be willing to look, in an objective way, at the facts about the unfairness of the justice system, the shocking indifference to guilt or innocence in relation to the death penalty, the insufficiency of defense for the accused, the enduring economic consequences of the racial housing discrimination (known as redlining), the persistence of unconscious and conscious bias in policing, the horror of mass incarceration (with all its racially tinged undertones) and its continuing impact even after the debt to society has been paid. And all of that doesn’t even get at what preceded these horrors–the evil of chattel slavery, the travesty of sharecropping, the terrorism of lynching, the degradation of Jim Crow.