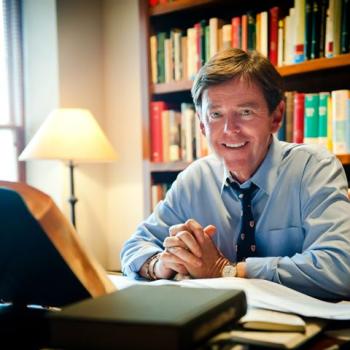

By Philip L. Tite

This year’s annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion (AAR) and the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) was a fun experience. I went through the typical routine of attending a smattering of sessions, connecting up with friends and colleagues, meeting new people, meandering through the book exhibit looking for interesting titles and good deals, and finally exploring a new city (I had never been to San Francisco before).

Attending the AAR/SBL meeting also offers me a good opportunity to pick up on emerging or enduring trends in the field. In one session I attended, for example, the theme of wealth or economy in early Christianity was explored. This was a fascinating session, with some wonderful papers that addressed a range of texts, social dynamics, and economic influences on those dynamics (e.g., exploring the intersection of trade routes with the emergence of communication networks). However, in this same session I noticed that nearly every speaker invoked the terms “orthodox”, “proto-orthodox”, or “mainstream” in their selection and explanatory treatment of their sources. Several speakers openly indicated their need to delimit their source base to a manageable level (which makes perfect sense as each paper is allotted only 20 minutes), with that delimitation excluding heterodox works or groups.

This model for selection evokes an enduring meta-narrative that continues to dominate religious studies, especially in biblical and patristic studies. This meta-narrative is that of orthodoxy and heresy/heterodoxy – i.e., “authentic” and “inauthentic” religion. We’ve inherited this model, in early Christian studies at least, from the Church Fathers, at least since Irenaeus (late second century), likely also Justin Martyr (mid-second century), and this model certainly is the ideological framework for Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History in the fourth century. The Greek term hairesis simply means “choice” or “path” (such as choosing to follow a particular career or adhere to a particular philosophical school of thought), but by the time we reach Justin, the term had taken on inherently negative connotations (“bad choice”). Those groups or individuals who were labeled “heretics” were seen as innovators of novel ideas (rather than adhering to established truths; i.e., those set down by the apostles as understood by the Church Fathers), as parasitical entities that preyed upon the true church. For Eusebius in particular the history of the church falls into two major trajectories: a lineage of apostolic truth, and another lineage of heretical teachers.

Read the rest here