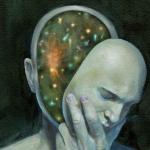

For years it has been lamented that humanist groups and events lack adequate participation by racial minorities. “Our philosophy is inclusive,” goes the refrain. “Our doors are open. Anyone can come.” Nonetheless, the usual overwhelmingly white demographic remains substantially unchanged.

We imagine we understand why. African-American and Hispanic communities are without freethought traditions, we argue, and longstanding religious orientations are built into their cultures. Therefore it’s up to us to bring humanism to them and hopefully overcome a longstanding bias against it. But, it turns out, that would be like bringing cheese to Wisconsin.

There is already a robust freethought tradition in the black community, for example. We can go back at least as far as abolitionist Frederick Douglass. NAACP cofounder W. E. B. Du Bois is another prominent example. During the Civil Rights movement of the 1940s through the ’60s the leader of its well-established secular wing was journalist and union organizer Asa Philip Randolph. He organized the 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Randolph was later recognized in 1970 by the American Humanist Association with its Humanist of the Year Award. Another such activist was Freedom Ride organizer James L. Farmer Jr., founder of the Congress of Racial Equality and the 1976 AHA Humanist Pioneer. Beyond social justice advocacy, we find the arts overflowing with prominent black freethinkers. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s through the ’40s, writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larson, and Richard Wright could be counted among them. Emerging later were jazz saxophonist and composer Charlie “Bird” Parker, author James Baldwin, and novelist Alice Walker, who was named the 1997 Humanist of the Year.

Read the rest here