by Rashad Grove

Rhetoric Race and Religion Contributor

It was Ralph Ellison who wrote in the prologue of his acclaimed novel, Invisible Man, “I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible; understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.” This reflection has prognosticative implications that bear witness in our world today.

The dilemma of the invisible is still actively alive and doing quite well in this present moment. There is a great chasm, a gulf, which separates the “seen” from the “unseen”. The reality that we are forced to encounter is that the invisible are in this state not by personal preference but rather by democratic design. There is public policy, proclaimed theology, culturally bias sociology, and racist, sexist, xenophobic, and homophobic anthropology that survives and thrives from the hierarchy that exist between the visible and the invisible. It’s critically imperative for us to understand that how one is viewed or “seen” denotes a level of value and importance in society. If that is the case, how one is “not seen” speaks to the tragic narrative of assumed purposelessness and futurelessness.

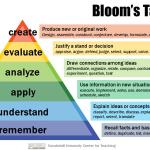

I believe that it should be the pathos of the prophetically influenced, inclined, and informed pastor, minister, academic, professor, teacher, activist, citizen, and human being to engage in the kind of ministry, vocation, and compelling creative enterprise that is foundationally established upon the pursuit of seeing through invisibility. This may not be as easy as it seems. The narrative of America has always been brutally honest about who matters and who doesn’t, who is “peopled” and who is “propertied”, who are white men and who are not, and who are human beings and who are savages. Out of the African Diasporic context, Cornell West brilliantly elucidates this argument in his provocative book Prophesy Deliverance: An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity. He says, “The notion that black people are human beings is a relatively new discovery in the modern West.” The social control and therefore the profitability of invisibility has been the fuel that accelerated the growth and power of the American experiment. The residue of this reality is pervasive in modern experience. The prison industrial complex that locks up black men and women at alarming numbers renders them invisible. With one-third of our nation in poverty, it ushers them into invisibility. A shrinking middle-class and the possibility of the obliteration of collective bargaining (I’m thinking of a state named Wisconsin.) propels a class of people into invisibility. The privatization of the public school systems (Philadelphia and others) renders students, parents, guardians, educators, administrators, communities, and an entire workforce that is connected to the system shamelessly invisible. The challenging interrogative becomes, “What should we do? We fight to be seen and we fight for how we are seen and what we are seen for.

Any casual observer of the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth has to come away realizing that the premise of the ministry of Jesus was the seeing of the invisible. The Roman political structure and the Jewish religious aristocracy perpetuated invisibility at their own gain. But Jesus, the Liberator and Revolutionary, challenged the normative societal functionality. In His eternal estimation, everyone has the God-given right to be seen. He saw the invisibility of the women who had no rights in patriarchal living system, those who were mentally and physiologically afflicted, the vulnerabilities of children and non-traditional families, the impoverished, and every other disillusioned, disenchanted, and disinherited person who He approximated with. Everything He did was based on the fact that everyone should be and has to be seen. That must be our motif. Regardless of race, ethnicity, political proclivity, gender, sexual orientation, economic class, we all deserve to be seen.