By Earle Fisher

R3 Contributor

*This is an excerpt of a paper originally presented at the National Council of Black Studies on March 14, 2013 in Indianapolis, Indiana

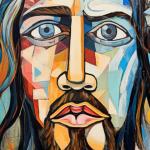

One of the classic works on prophecy is Abraham Joshua Heschel’s “The Prophets.” Heschel projects theories of God’s connection to the ancient 8th century Hebrew prophets of the Old Testament and eloquently waxes concepts relative to their psychology, rhetoric and mission.

As is the case with conventional concepts of covenantal theology, we must see Heschel’s works as relatively one sided also. He seems to be conditioned to tilt towards an affirmation of Jewish theological sensibilities, even at the expense of theological concepts that predate Hebrew prophecy. It is known that ancient Jewish, Israeli and Hebrew theology is a bi-product of notions and concepts of God from other ethnic groups (namingly African and Mesopotamian). Heschel and others have centered thoughts relative to prophecy and the prophetic tradition primarily on the Old Testament prophets. Yet, R. E. Clements had already begun conceding that canonical prophets were not necessarily originals. This means that as we construct a prophetic theology we ought not to be bound to biblical witness alone. Often times for the contemporary church the Bible is the pivot point for more interpretive problems than it is inspirational solutions. According to Clements, “…work of the canonical prophets arose out of the activity of a much larger prophetic movement in Israel…” It seems obvious to me that if what is represented canonically is not exhaustive of the movement in Israel, clearly, there are other movements, traditions and sacred texts that share similarities and are in need of consideration as we lay the foundations of prophetic theology. Nevertheless, Heschel does highlight the shift towards a prophetic theology that is saturated with concepts of prophetic persona, theodicy, pathos and concern for those who are oppressed.

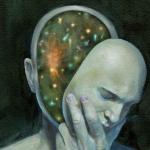

Along with the past works of Heschel, more contemporary seeds of prophetic theology have already been planted through the work of Dr. Andre Johnson and his rhetorical work on prophecy, especially his work on Bishop Henry McNeal Turner. Johnson grounds his work in what he calls “prophetic rhetoric.” For Johnson, prophetic rhetoric is one of the vehicles at the prophet’s disposal to persuade his/her community to adopt the ideas the prophet has for the alternative vision of existence. These ideas, in my estimation, are seeds of evidence we can use to construct our prophetic theology. Johnson defines prophetic rhetoric as, “discourse grounded in the sacred and rooted in a community experience that offers a critique of existing communities and traditions by charging and challenging society to live up to the ideals espoused while offering celebration and hope for a brighter future.”

What I believe Johnson offers through his interpretation on prophetic rhetoric, is a chance to interrogate what theological concepts would cause one (or inspire one) to use such speech. This is the platform for us to construct prophetic theology.

I posit that prophetic theology is a constructed concept of God that inspires one to use their gifts, skills, imagination, creativity and privileges to empower and equip those who are underprivileged. This type of theology is rooted in theories relative to justice, love and mercy for all peoples. It is not mere morality but a cosmological theology that includes humanity in the production of peace, even when that peace comes as a result of painful sacrifice or martyrdom. It is not mere social criticism but a “fire shut up in the bones” of one who deeply believes God is displeased with the state of society and thereby calls one to act using rhetorical and other vehicles of persuasion to improve the environment. The theology of the prophets has historically sought to represent God’s will on behalf of those who are at the margins of society; the powerless

, forgotten and left behind. I also contend that prophetic theology is not necessarily biblical theology. This makes prophetic theology (and thereby those who embrace such) more inclusive and sensitive by proxy. Prophetic theology is one that honors the best and brightest of the religious tradition yet has the courage and gumption to speak truth to power when the power is tilted towards the strong and not the weak, especially when this power is a religious and ecclesiastical power. Prophetic Theology is grounded in a love ethic which challenges its constituents to practice what they preach and thereby remain sensitive to the plight of the poor and oppressed even if it means changing their own place of residence. Unlike that (racist) systematic theology of the past, the theology of the prophets use divine inspiration to empower others and addresses the conformity and complacency of those who claim to walk in the ways of God or what Walter Brueggemann calls, “Royal Consciousness.” Prophetic theology is courageous, honest and cannot be commodified (in part, because it doesn’t pay well to speak out against those who have the most resources when they have used their resources to maintain power and privilege). We must study the prophetic tradition to ensure that we are intentional when we represent God’s will for humanity.

Prophetic theology, unlike legalistic, dogmatic and oppressive theology, is not concerned with a personal piety as established by the status quo. While legalistic theology attempts to affirm righteous works based upon the maintenance of hegemonic control, prophetic theology realizes that righteous works will often times cause one to be marginalized, outcaste and even killed. Nevertheless, if we are to reclaim those who we have neglected, forsaken and forgotten, we must embrace and incorporate a more prophetic theology realizing that many of the systems we have set up (even in the name of God) have been anything but just and fair to the least of these.

Therefore those who stand in the prophetic tradition today (the contemporary prophets) are still being discerned and at the very least express evidence of having constructed an understanding of God through a prophetic theology –not just a theological sound-bite or proof-text.

If we are to revive and salvage the religious fervor and Spirit of Jesus and other ancient prophetic figures, these shifts from pimpish proselytizing and irrelevant religion to a more covenantal, prophetic and inclusive theology must be made. Until then, we will continue to (both knowingly and unknowingly) abuse, marginalize, oppress and even kill others in the name of righteousness.