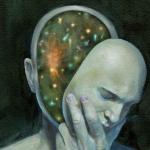

In his book War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, war correspondent Chris Hedges tries to explain why he became so addicted to war that he could not live without being in a war. War had quite simply captured his imagination, making it impossible for him to live “normally.”

“I learned early on that war forms its own culture. The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug, one I ingested for many years. It is peddled by myth makers – historians, war correspondents, film makers, novelists, and the state – all of whom endow it with qualities it often does possess: excitement, exoticism, power, chances to rise above our small stations in life and a bizarre and fantastic universe that has a grotesque and dark beauty. It dominates culture, distorts memory, corrupts language, and infects everything around it, even humor, which becomes preoccupied with the grim perversities of smut and death … The enduring attraction of war is this: Even with its destruction and carnage it can give us what we long for in life. It can give us purpose, meaning, a reason for living. Only when we are in the midst of conflict does the shallowness and vapidness of much of our lives become apparent. Trivia dominates our conversations and increasingly our airways. And war is an enticing elixir. It gives us resolve, a cause. It allows us to be noble.”

According to Hedges, war makes the world coherent, understandable, because in war the world is construed as black and white, them and us. Moreover, Hedges notes that war creates a bond between combatants found almost nowhere else in our lives. War does so because soldiers at war are bound by suffering for the pursuit of a higher good. Through war we discover that though we may seek happiness, far more important is meaning.” And tragically war is sometimes the most powerful way in human society to achieve meaning.”

The meaning often assumed to be given by participation in war, particularly in the West, draws on the close identification of the sacrifice required by war and the sacrifice of Christ. Allen Frantzen, in his extraordinary book Bloody Good: Chivalry, Sacrifice, and the Great War, calls attention to the continuing influence of the ideal of chivalry for how English and German soldiers in World War I understood their roles. He notes that development of chivalry depended on the sacralisation of violence so that the apparent conflict between piety and predatoriness simply disappeared. Instead the, great manuals of chivalry “closed the gap between piety – which required self-abnegation and self-sacrifice – and violence rooted in revenge. The most important presupposition of chivalry became the belief that one bloody death – Christ’s – must be compensated by others like it.” Drawing on extensive pictorial evidence, Frantzen helps us see that the connection between Christ’s death and those who die in war is at the heart of how the sacrifice of the English, Germans and Americans who died in World War I was understood.

Read the rest here