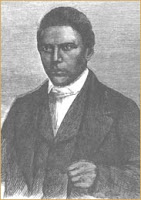

by Andre E. Johnson

by Andre E. JohnsonR3 Editor

* This is the second of a four part series. Read the other installments here.

Chaplain Henry McNeal Turner’s writings during the Civil War covered a wide range of topics. One of the first letters was a tenderhearted eulogy of the Rev. Mrs. Weaver—wife of the then editor of the Recorder—Elijah Weaver. Turner in comforting his friend wrote:

Your wife died in the full triumph of a blessed resurrection. You are assured of her entrance into the kingdom of heaven. She that was recently your afflicted wife on earth, is now your sainted wife in the skies. She is still your wife, a sainted wife, a redeemed wife, a sin-conquering wife, a wife who stood fearless amid death’s cold waters as they heaved and rolled in angry billows while passing over the Jordan. It is true that you will feel her loss, but when you see others conversing with their wives on earth, you can with a joyful anticipation of meeting her, raised your hand and point to heaven and boast of a wife saved by grace and housed forever in God’s eternal favor (Johnson, 19).

One topic of course was the battles that he witnessed. The most famous battle that his unit fought was the battle of Fort Fisher. In thrilling detail, Turner captured the battle in a series of letters to the Recorder. In one, he wrote of while he and the others men were eating, the shout of “the rebels, the rebels,” echoed throughout the camp. Turner further wrote:

Notwithstanding many were at dinner, down fell the plates, knives, forks, and cups, and a few moments were only required, to find every man, sick or well, drawn into line of battle to dispute the advance of twice, if not thrice, their number of rebels. Captains Borden and Rich, of the 1stU.S. Col’d Troops, with their gallant companies, were at some distance in front, skirmishing with the advance guard of the rebels. And here permit to say, that this skirmish was the grandest sight I ever beheld. I acknowledge my incapacity to describe it, and thus pass on. By the time our pickets had been driven in, a flag of truce was seen waving in the distance, when Gen. Wild gave orders to cease firing (Johnson, 25-26).

Turner wrote about his battalion of soldiers and the horrors of war. In writing about the destruction of an ordnance, Turner noted

Turner wrote about his battalion of soldiers and the horrors of war. In writing about the destruction of an ordnance, Turner notedA pile of dead men had been collected and placed on the hill, some of whom looked frightfully mangled, while pieces of human bodies lay in terrific profusion in every direction….Some dear wife will anxiously await her husband’s arrival; some father his son; some sister her brother, and so on, but they never will come. The place was crowded with people as is always the case, therefore they suffered irrespectively (Johnson, 34).

He also wrote about especially how the “rebel” soldiers killed unarmed and surrendered Union soldiers, especially blacks. However, Turner did not agree with exacting vengeance.

There is one thing, though, which is highly endorsed by an immense number of both white and colored people, which I am sternly opposed to, and that is, the killing of all the rebel prisoners taken by our soldiers. True, the rebels have set the example, particularly in killing the colored soldiers; but it is a cruel one, and two cruel acts never make one humane act. Such a course of warfare is an outrage upon civilization and nominal Christianity. And inasmuch as it was presumed that we would carry out a brutal warfare, let us disappoint our malicious anticipators, by showing the world that higher sentiments not only prevail, but actually predominate (Johnson, 26).

Turner also called for family members and friends to write the soldiers. In writing to the Recorder on how tough pen and paper was to get at times, he nevertheless called for loved ones to write to the soldiers.

No one knows, in civil life, how much a soldier appreciates a letter from those whom he regards as near and dear to him. In many instances our soldiers will beg paper and ink enough to write to some dearly beloved wife, brother, sister or friend who would apparently shake their hand off at home, and after receiving their letter, they are too contemptibly lazy to answer it. I know this from experience; for often; when I am traveling, persons will say to me, Chaplain, tell such a one, I received his two or three letters, and he must write again. They don’t know that some of the letters sent to them cost a very big price, for many of the soldiers who can’t write themselves, have to pay others to do it for them. And sometimes, it is almost impossible for a soldier either to get paper, ink, pen, or pencil. Any wife that is a wife, or friend that is a friend, or relative that is a relative, should never think it too much to write to a soldier two three or four times, before getting an answer from him (Johnson, 32-33).

Turner did not have any patience for the wife who would leave her husband while her husband was at war. In writing about the three soldiers who were under “mental anguish” to learn that their wives had married and “taken up with other men,” responded when asked his opinion, “let them go to the devil!” Further, he wrote:

Any cowardly civilian, who would take advantage of a brave soldier’s wife, on account of her poverty, owing to her husband receiving only seven dollars per month and the failure of the Government to pay him regularly, ought to have his rotten tongue pulled out by the roots, his throat cut, his heart burned, and his infamous carcass devoured by snakes (Johnson, 42).

It was these and many other letters, which Turner wrote that, gave a glimpse of the lives of the African American Union soldiers.

To be continued……

To be continued……

Works Cited

Johnson, Andre E. and Henry McNeal Turner (ed). An African American Pastor Before and During the American Civil War. The Literary Archive of Henry McNeal Turner, Vol 2: The Chaplain Letters. Edwin Mellen Press, 2012