R3 Editor

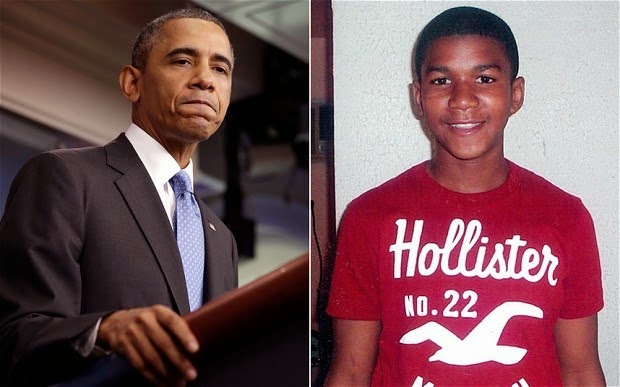

On July 19, 2013, President Barack Obama delivered by all accounts, an impromptu speech responding to the verdict in the George Zimmerman case. The jury in the case found Zimmerman not guilty of the murder of Trayvon Martin in February 2012. The verdict prompted surprise and outrage and caused many to question yet again the justice system and its fairness when it came to African Americans seeking justice. What also surprised many pundits was that Obama responded the way he did at all.

Immediately after the verdict, the president issued a statement that while calling the death of Trayvon Martin “a tragedy,” he also reminded Americans that we are a nation of laws and that the jury had spoken. He further challenged Americans “to respect the call for calm reflection from two parents who lost their young son.” He called for Americans to “ask ourselves if we’re doing all we can to widen the circle of compassion and understanding in our own communities.”

We should ask ourselves if we’re doing all we can to stem the tide of gun violence that claims too many lives across this country on a daily basis. We should ask ourselves, as individuals and as a society, how we can prevent future tragedies like this. As citizens, that’s a job for all of us. That’s the way to honor Trayvon Martin.[1]

Obama’s short statement after the death of Trayvon Martin also reminded observers of the delicate balance the president has to navigate when speaking of race-sensitive topics. Obama quickly learned this lesson back in 2009 when he commented that the police acted “stupidly” when an officer arrested African American Harvard professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates at his home for disorderly conduct. After the infamous beer summit and after the DA assigned to the case elected not to charge Gates for disorderly conduct, nevertheless, the incident caused a huge drop in the president’s approval ratings among white voters. Since this incident, during both his first and second terms, it would seem that the White House has elected not to get involved in race charged incidents.[2]

However, Obama’s speech in the Press Briefing Room served as a departure from his silence on race since the Gates incident. Instead of issuing a carefully worded statement that did not mention anything about race, Obama decided it was time to broach the subject. According to the New York Times,[3] after days of “angry protests and mounting public pressure,” the president summoned five of his top advisers to the Oval Office to talk about a verbal response to the George Zimmerman verdict.[4] According to one of the president’s senior aides, Obama spoke “without interruption” for about fifteen minutes on “why the not-guilty ruling had caused such pain among African-Americans.” After hearing from the president and his determination to make a statement, his team decided that Obama should speak about the verdict in “brief interviews with four Spanish-language television networks.” That plan did not work because none of the interviewers asked him about the verdict. Therefore, without any advance warning Obama appeared in the press briefing room and delivered his response to the George Zimmerman verdict.

In this presentation, I argue that through a close reading of a portion of the speech, Obama frames the killing of Trayvon Martin and the subsequent acquittal of George Zimmerman through the lens of blackness. In short, Obama articulates to the American people the pain that African Americans felt after the verdict. Moreover, I argue that by framing black pain at the center of this “American tragedy,” Obama invited all Americans to see “blackness” and its pain as part of the American fabric.

After reassuring the press corps that Jay (Carney) was going to take their questions and after reiterating his earlier statement, Obama framed the speech within the context of understanding “how people have responded to it (the verdict) and how people are feeling.” What Obama invited his audience to do was to imagine and maybe even to see how others responded to the verdict—a verdict that many found unjust.

Then Obama shifts into the major part of his speech. He starts by saying that “You know, when Trayvon Martin was first shot I said that this could have been my son.” However, after the verdict, Obama adds another way of interpreting his previous statement—“Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago.” Framed this way, the president moves from locating himself as a parent of a slain teen to a more concrete position—he locates his own body with that of the slain Trayvon Martin.

By doing this, Obama does two things. First, when he says Trayvon “could have been my son,” he stands with not only the parents of Trayvon but also all parents who have had to grieve that death of a child by gunfire—and second, Obama’s comment “Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago,” now shifts the issue to its current position. What the president wants to invite his audience to do is to see him as Trayvon Martin and to begin to understand some of the frustrations fr

om a portion of American—African Americans.

Next, he locates this experience with this:

There are very few African American men in this country who haven’t had the experience of being followed when they were shopping in a department store. That includes me. There are very few African American men who haven’t had the experience of walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars. That happens to me — at least before I was a senator. There are very few African Americans who haven’t had the experience of getting on an elevator and a woman clutching her purse nervously and holding her breath until she had a chance to get off. That happens often.

By framing his narrative this way, Obama places himself with the many people who find themselves racially profiled. “That includes me,” signifies the complete understanding of this feeling—whereas “at least before I was a senator indicts not a removing of the racism, but an elevation of class and notoriety. While as he admits, since becoming a senator, he has not been subjected to racial profiling; Obama does not dismiss the racial profiling from others. In short, Obama’s critique that racial profiling continues remains as he moves to the elevator comment of women clutching their purses when African Americans get on the elevator.

After not wanting to exaggerate this (speaking of racial profiling and race biases), Obama suggests that those “sets of experiences inform how the African American community interprets what happened one night in Florida and “it’s inescapable for people to bring those experiences to bear.” Further, he surmises

The African American community is also knowledgeable that there is a history of racial disparities in the application of our criminal laws — everything from the death penalty to enforcement of our drug laws. And that ends up having an impact in terms of how people interpret the case.

Obama argues that African Americans not only see the case from their own perspective, but they have reason to see the case this way. In short, the president validates African American interpretation of the Zimmerman case. African Americans are not crazy, too sensitive, or too radical—there is a “history of racial disparities” that give rise to these feelings and it shapes the way many African American interpret the case.

Obama continues this line of thinking when he speaks on the frustration of African Americans when he notes that

African American boys are painted with a broad brush and the excuse is given well, there are these statistics out there that show that African American boys are more violent — using that as an excuse to then see sons treated differently causes pain…….But they get frustrated, I think, if they feel that there’s no context for it and that context is being denied. And that all contributes I think to a sense that if a white male teen was involved in the same kind of scenario, that, from top to bottom, both the outcome and the aftermath might have been different.

Here, Obama not only shares the frustration of many African Americans and the excuses that folks use to treat sons differently, Obama also offers a new way to see this incident. By introducing a different “scenario,” adding a white male teen to the mix instead of a black teen, Obama, while careful not to agree himself, suggests that many African Americans see the case this way.

After offering some directions and suggestions that American can do to honor the memory of Trayvon Martin, Obama closes this part of the speech with a powerful reflection.

And for those who resist that idea that we should think about something like these “stand your ground” laws, I’d just ask people to consider, if Trayvon Martin was of age and armed, could he have stood his ground on that sidewalk? And do we actually think that he would have been justified in shooting Mr. Zimmerman who had followed him in a car because he felt threatened? And if the answer to that question is at least ambiguous, then it seems to me that we might want to examine those kinds of laws.

Obama offers a reversal in “black fear.” In Obama’s reshaping of the narrative, by placing a gun in an “of age” Trayvon Martin’s hand, the president can then, by way of rhetorical question ask could Trayvon Martin “have stood his ground on that sidewalk?” Further, by asking again rhetorically, “do we actually think that he (Martin) would have been justified in shooting Mr. Zimmerman who had followed him in a car because he felt threatened,” the president does two things.

In examining a portion of Obama’s remarks after the Zimmerman verdict, I argue that for the first time, America heard its president not only describe black pain, but also affirm its manifestation. I suggest this is new to the American experience—that previous presidents, Democrats or Republicans have not articulated the pain of the African American experience. Moreover, while I demonstrate that he does it here in this speech, this critique prior to the speech would have included Obama as well. The reaso

n why this speech was a surprise to many was the fact that Obama continuously has stayed away from race themed topics throughout both terms.

However, for whatever reason, Obama decided on that day to speak about an issue important to many Americans. By speaking on the Zimmerman verdict, Obama used the bully pulpit to not only speak on the issue of race and racial biases and profiling, but also include again African Americans into the nation’s fabric. This time, the president of the United States, the president for all the people, offered a pedagogical speech in which he attempted to explain and teach to some, why some African Americans felt hurt and betrayed, yet again by a system that many tell them to trust. In doing so, he brought issues germane to the African American community to the forefront and reassured the African American community that he in fact does see and the African American pain is part of the fabric of America—that when one hurts, we all hurt.

[1] Statement by the President. July 14, 2014. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/14/statement-president

[2] See Arrest of Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates Jr. was avoidable, report says. June 30, 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/06/30/AR2010063001356.html, Obama Addresses Race and Louis Gates Incident. July 23, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/22/AR2009072203800.html, Gates, Police Officer Share Beers, Histories With President. July 31, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/30/AR2009073003563.html, Obama Involvement in Gates Flap Hurt Image, Poll Finds. July 31, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/30/AR2009073004097.html

[3] President Offers a Personal Take on Race in U.S. July 19, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/20/us/in-wake-of-zimmerman-verdict-obama-makes-extensive-statement-on-race-in-america.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

[4] The Times called it the Trayvon Martin verdict. It was the George Zimmerman verdict.

[5] Remarks from the President on Trayvon Martin. July 19, 2013. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/19/remarks-president-trayvon-martin