Post appeared first on the Anxious Bench Blog

Post appeared first on the Anxious Bench Blog

The St. Louis County grand jury tasked with determining whether enough evidence exists to indict Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson in the shooting death of Michael Brown will announce its decision later this month. Regardless of the outcome of that inquiry, large groups of people will be disatisfied, even angry. Unfortunately, their reaction will not be determined by the details of the grand jury inquiry and what the evidence shows, but have been predetermined based on assumptions about race–evidence of the racialized nature of our society.

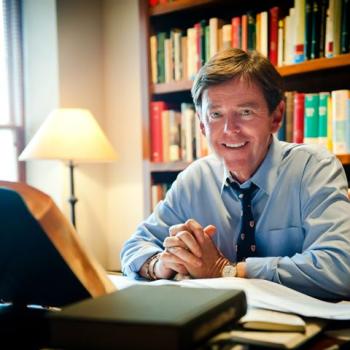

Last week, one of my lectures, “America in Black and White,” addressed the challenge of race in America. I had given this lecture before, but in a different environment. In the “free world,” the lecture and ensuing discussion had a more academic feel. This time, in the prison where I teach, it was more poignant.

In the free world, we discuss race in muted tones, if at all. For the most part, whites live in one neighborhood and blacks another. We interact at the margins, using our best manners. Race remains undiscussed until something like the Rodney King beating, the O.J. Simpson trial, or the death of Trayvon Martin or Mike Brown catapults us towards a fiery discussion.

The occupants in a prison do not have such luxuries. They are literally forced to lived together, with no chance to opt out by moving to another neighborhood. Racially-grounded gangs are commonplace. Prisoners know what many of us choose to ignore: that race matters profoundly in America. They understand–better than I do–that we do not live in a color-blind or post-racial society. We live in a racialized society.

Racialized is the term that Michael Emerson and Christian Smith employ in Divided by Faith (2000) to describe “a society wherein race matters profoundly for differences in life experiences, life opportunities, and social relationships (7).” Statistically, it is an incontrovertible fact that race matters profoundly in America in those ways. Further, these differences in experiences, opportunities, and relationships shape how we see the world, forming our interpretive lenses, and, indeed our prejudices. Thus, when hear of a tragic event that touches on race, we have different expectations of what the facts will reveal once they are uncovered or what the “real story” is if evidence fails.

I tried to convey that reality to my class in this way: “Think back,” I said, “to the first time you heard about the death of Trayvon Martin or Michael Brown. Without knowing the details or having heard the facts of the case, each of you reacted in a particular way based on assumptions–prejudices, if you will–that you had about the kind of people involved. And that, in and of itself, is proof that we live in a racialized society in which race still shapes our thoughts and actions.”

By the time I had finished, an unusual hush had settled over a typically vocal and animated class. I had hit a nerve, describing something we all knew was true. To their credit, I also know these men well enough to know that they wished it were not.