I do not know much of anything about “the evolution and ecology of microbes and genomes,” or much of anything about Dr. Jonathan Eisen, who specializes in that field. But Eisen seems to be a mensch.

The UC Davis professor was recently invited to give a prestigious endowed lecture series and, as Upworthy would say, What He Did Next Will Surprise You.

I do not think I have ever given a named lecture before. Then I made one fateful decision — I decided to look up who had spoken at the lecture series previously. And, well, it was not what I wanted to see. And another lecture series from the same institute had the same problem. Bad gender ratio of speakers.

So he responded to the invitation with a polite No, Thank You, explaining why, and urging the organizers of the lecture series to instead take the opportunity to correct that ratio:

Thank you so much for the invitation and the respect it shows to me that I would be considered for this. However, when I looked into past lectures in this series I saw something that was disappointing. From the site XXXX where past lectures are listed I see that the ratio of male to female speakers is 14:3. I note — the XXXX lecture series — also from XXXX — also has a skewed ratio (11:2). As someone who is working actively on multiple issues relating to gender bias in science, I find this very disappointing. I realize there are many issues that contribute to who comes to give a talk in a meeting or seminar series or such. But I simply cannot personally contribute to a series which has such an imbalance and I would suggest that you consider whether anything in your process is biased in some way.

The organizers’ reply to Eisen offered a bit of the usual defensiveness — explaining that they’d tried to invite more women to speak, etc. — but to their credit, they eventually arrived at something a bit more constructive, asking Eisen to: “recommend female researchers in this area who are dynamic speakers that would be able to give a very publicly accessible talks (TED talk level) on the topic, and ideally are also doing great research too.”

Dr. Eisen leapt at the opening — recommending a bunch of women in his field with great enthusiasm.

What I appreciate most about Eisen’s account of this process is where he says that he made “one fateful decision.” By that he didn’t mean his later ensuing decision to decline the invitation — he doesn’t seem to consider that a decision at all. The only decision he made was the initial one — “I decided to look up who had spoken at the lecture series previously.” He decided to look, and once he had looked, and seen, everything that followed after that was simply the necessary consequence of having looked. Once you look and see, the ensuing decisions are no longer really optional.

The honor of being invited to give a prestigious lecture, Eisen writes, “would be really nice.” But the niceness of that honor loses its appeal once he realizes that it would involve him becoming complicit in perpetuating a disappointing pattern — turning that 14:3 ratio into an appalling 5:1.

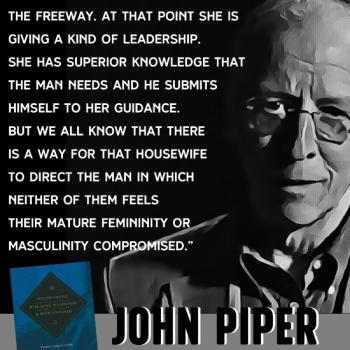

For us white guys in the American church, it can be really nice to be invited to speak at conferences, to sit on panels, boards, and drafting committees. Such invitations are an honor — one that may even come with honoraria (which is also, you know, really nice). But that honor begins to seem much less honorable once we make the fateful decision to look.

And once we look, we’re obliged to follow Eisen’s example — to say “No, thank you” and to be prepared to wholeheartedly recommend others in our stead.

Go thou and do likewise.