Richard Beck is one of my favorite bloggers and one of the kindest, wisest people in my RSS feed. He’s someone I like and admire so much that I’ll offer this kind of gushing praise for him even when it’s not in anticipation of a qualifying “but” to follow.

But … (And this disagreement on one point in no way diminishes any of what I’ve just said. Seriously, bookmark his blog. Subscribe. Read it. Absorb it. It’s terrific stuff and he is, himself, a mensch.) … but …

I appreciate the main thrust of Beck’s post yesterday on “Christus Victor and Progressive Christianity,” … but … I think he’s overlooking a great deal of what progressive Christianity is saying. And also overlooking a great deal of what mainstream white evangelical Christianity is incapable of saying.

Christus Victor is a theory of the atonement that says Jesus died and rose to free us from bondage to sin, death and evil. A lot of people who are sometimes called “progressive Christians” find this a more appealing explanation for the meaning of Christ’s death and resurrection than, say, the more recent penal substitutionary theory of atonement, which seems to imply an unlovely, vindictive bloodthirstiness on the part of God. (Not that every progressive type Christian would go so far as to describe penal substitutionary atonement as a ghoulishly Lovecraftian horror — but some of us might say exactly that.)

Hence the appeal of alternative theological theories, including Christus Victor.

The problem, Beck says, is this:

For Christus Victor theology to make any sense you have to have a robust theology of those dark enslaving powers, a robust theology regarding our spiritual bondage to the powers of death, Satan and sin. And yet, because of their pervasive struggles with doubt and disenchantment, along with their post-evangelical reluctance to talk about our enslavement to sin, progressive Christians lack an important aspect of Christus Victor atonement: a vision of enslavement to dark spiritual powers.

Basically, what are you being rescued from if you aren’t enslaved to anything in the first place?

Progressive Christians like the idea of Jesus spiritually rescuing us but they do a damned poor job of describing how all of us, without Christ, are in spiritual bondage. But without a robust vision of spiritual slavery and bondage in the hands of progressive Christians Christus Victor theology is a non sequitur, it just doesn’t make any logical or theological sense.

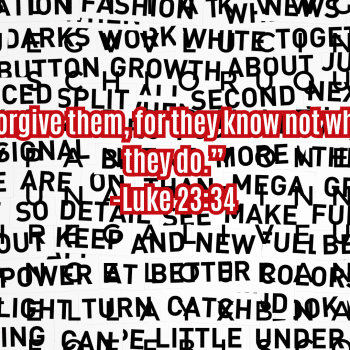

I appreciate the gist of that — we shouldn’t go around singing “We Shall Overcome” unless we’ve got a clear idea of what it is that needs overcoming. But if we listen to Christians on the progressive side of the church, I think we’ll find that they have a very clear idea indeed.

For me, this is part of the appeal of progressive Christianity. It articulates a powerful, liberating understanding of “spiritual bondage to the powers of death, Satan and sin.” The explanation and exploration of such spiritual bondage is far more serious and substantial than any corresponding effort I have seen in mainstream white evangelicalism. It is precisely this robust theology — the very thing Beck says here is lacking — that has drawn me and many, many others to look beyond the individualist white-evangelical piety of a “personal Lord and savior.” We were looking for something that could help us to make sense of the world — and of the meaning of redemption, bondage, sin, and liberation.

And if that’s what you’re looking for — “a robust vision of spiritual slavery and bondage” to help make sense of the world — then progressive Christianity is a fruitful place to start. After all, where do you think “Liberation theologies” got their name? Or look to Walter Wink on the powers and principalities. Or to Reinhold Niebuhr on the pervasive corruption of pride and the way sin gets institutionalized, precluding sinless possibilities. Or to the recent wave of “empire” theory and criticism.

More importantly, should we imagine it’s possible to have anything like an accurate appreciation for the meaning of “enslavement to dark spiritual powers” without understanding the role of powers and principalities like racism, patriarchy, class, privilege, violence, nationalism, colonialism, etc.? Does anyone really believe that conservative white, male, American evangelical theology offers an adequate understanding of any of those things?

No, if you want to truly understand “our spiritual bondage to the powers of death, Satan and sin,” then you’re going to have to read theologians of color, feminist and womanist theologies, queer theologies, liberation theologies and other theologies of the poor. Those voices are, shamefully, often marginalized even within nominally “progressive” Christianity, but if we’re speaking in broad, general terms about “progressive” and “conservative” camps, then that progressive camp is where you’re going to find them.

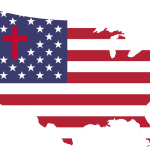

Let me go further than that. It is not progressive Christianity, but mainstream white evangelicalism that is “reluctant to talk about our enslavement to sin.” It is reluctant to do so because it is unable to do so. And it is unable to do so because it has, itself, become one of The Powers That Be — or, at least, it has become their faithful servant.

On the other hand, look at the proliferation of young progressive Christian voices in the blogosphere or on Twitter. I’m not sure that “pervasive struggles with doubt and disenchantment” are words I’d use to describe them. I look at them and I see liberation — people who have broken free from dark spiritual forces they have come to understand all too well.

(“Disenchantment” is an odd word. Like, “disillusioned.” it sounds bad — until you realize that its opposite sounds even worse. “Enchantment,” after all, is a kind of bondage. So maybe disenchantment can be a kind of liberation.)

Look at the plethora of young women offering insightful critiques of purity culture, modesty culture and rape culture. Look at the amazing, ongoing discussions of racism, white supremacy and white privilege that Christians (among many others) have been having around #Ferguson. (Including the related discussion of how the term “progressive Christian” can be, itself, a tool of white privilege, supremacy and hegemony.) What are those conversations if not, in fact, expressions of “a robust vision of spiritual slavery and bondage”?

And what is the alternative that these progressive Christians have allegedly turned away from? Where in mainstream white evangelicalism can we find a superior understanding of the meaning of spiritual slavery?

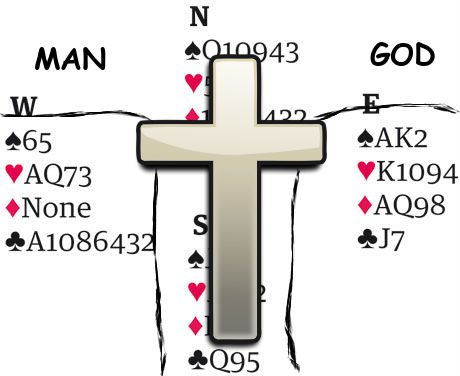

The Bridge Illustration from the Navigators is a classic expression of the white evangelical understanding of the meaning of sin. But that illustration is about estrangement, not enslavement.

How about The Screwtape Letters?

Don’t get me wrong — I love The Screwtape Letters. I have an audio version of it read by John Cleese that I think is just about the most perfect marriage of text and narrator ever recorded. It’s an insightful, wise, sometimes profound, often hilarious self-help book. It’s a self-help book that offers some immensely helpful spiritual advice. But having said all that, it’s still a self-help book. It deals with the self by itself — detached and excerpted from all social context. (Or, perhaps, presumed to share the same unconsciously normative context of Lewis’ self.) Like most of what you’ll find in mainstream white evangelical discussions of “enslavement to sin,” it has far more to say about spiritual bondage to bad personal habits than it does about spiritual slavery and bondage.

Poor Wormwood turns out to be a hapless tempter, but his devilish uncle isn’t much more effective. Neither of them gives much thought to the weightier matters of justice, and so they are ultimately unable to prevent their subject from finding redemption, salvation and liberation. Screwtape should have read more widely, seeking infernal inspiration from the insights offered by the “robust vision of spiritual slavery and bondage” that he might have found in progressive Christianity.

Screwtape’s job, remember, was to imprison his subject in bondage to death and sin. He failed at that devilish task because his understanding of such bondage was limited to the shallow, inadequate, individualistic understanding of conservative white Protestantism.

If Screwtape had read James Cone or Martin Luther King Jr., he might have learned a thousand subtle ways to rot their subject’s soul with the corrosive effects of white privilege, white supremacy, and white guilt curdling into resentment. If he had read feminist theologians, he might have learned countless new tricks that could bind that subject’s soul in the oppressor’s oppressive chains of patriarchy, slowly turning him into a seething ball of Driscollian rage. Or Screwtape might have turned to the progressive Christianity of queer theology, inverting its insights into a prison that deceives the subject into thinking of equality as persecution.

I’m not arguing here that structural injustices trump personal sins. I’m not even arguing that participation in structural and social injustice is “weightier” than personal sin. What I’m trying to get at, rather, is the way that ignoring the existence of social injustice and our participation in it distorts our understanding of personal sin as well. We can’t say that white evangelicalism understands individual, personal sin while failing to understand social injustice. Because it fails to understand — or even acknowledge — social injustice, it cannot understand individual, personal sin either.

There’s a hole in white evangelicalism’s understanding of sin, death, evil and spiritual bondage. It’s a gaping chasm wider than the one in the Navigator’s bridge illustration. It’s the blind spot that allowed America’s first great theologian to write “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” before sitting down to a meal cooked by his slaves. Or the blind spot that allowed America’s first great revivalist to preach salvation from sin while simultaneously working to overturn the colony of Georgia’s ban on slavery.

It turns out that people who were enslaved to enslaving others weren’t in a good position to understand enslavement to sin. Yet from Edwards and Whitefield on, those blind spots have been woven into the fabric of white American Christianity.

A reluctance to affirm that failed understanding of “enslavement to sin” does not constitute a lack of a robust theology of spiritual bondage. It suggests, rather, a desire to instill such a robust theology where none has previously existed.