Broad strokes, here’s what happened.

The War on Drugs — or, as our friends at LGM call it, the War on [Some Classes of People Who Use Some Kinds of] Drugs — means that using peyote is against the law.

But peyote isn’t just a recreational drug. It also plays a role in some Native American religious ceremonies — and this is an actual thing, a bona fide religious practice that goes way back.

Alfred Smith was a member of the Native American Church. He also worked as a counselor at a drug rehab clinic in Oregon. But the clinic fired him because he participated in religious rituals using peyote and they didn’t want a “drug user” working as a drug counselor. Not only did he lose his job, but then the state of Oregon denied his unemployment insurance saying they didn’t have to pay to a guy who got fired for being a big ol’ druggie.

Smith sued, saying this was religious discrimination — which, of course, it absolutely was. This should’ve been a slam-dunk, no-brainer First Amendment case. Oregon was claiming that the War on Drugs gave them the right to enforce a law prohibiting the free exercise of religion. That’s bonkers.

Smith sued, saying this was religious discrimination — which, of course, it absolutely was. This should’ve been a slam-dunk, no-brainer First Amendment case. Oregon was claiming that the War on Drugs gave them the right to enforce a law prohibiting the free exercise of religion. That’s bonkers.

But the case wound up going all the way to the Supreme Court — Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, or just Oregon v. Smith. And in 1990, the top court ruled in favor of Oregon. It’s anti-peyote law may have had the effect of prohibiting Smith’s free exercise of religion, Justice Scalia argued for the majority, but since the War on Drugs wasn’t intended to pick on Native Americans, specifically, that was cool.

Bonkers.

Oregon v. Smith was a big departure from precedent and tradition. Think back to the Prohibition Era, when the country actually rewrote the Constitution in order to outlaw alcohol. But even at the height of Prohibition, neither the courts nor the public thought that ought to apply to the sacramental wine that was an essential component of the religious practice of millions of American Christians. But Scalia’s argument in Oregon v. Smith veered off from that earlier way of thinking.

So at that point, back in 1990, everybody who likes the First Amendment went ape. And I mean everybody — every religious group in the country, right or left, advocates for secularism, the ACLU, the Christian Coalition, you name it. This broad, transpartisan coalition pushed for a legal remedy to reassert that freedom of conscience shouldn’t be trumped by the War on Drugs or any other law that has the effect of discriminating against religious practice. Scalia’s decision had said that since the anti-peyote law wasn’t explicitly “an attempt to regulate religious beliefs,” then it didn’t matter that it had the effect of doing so. The coalition said it did matter, and they rallied behind a law that said so.

The result was the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. This was an attempt to reassert the earlier legal regime in which laws that had the effect — deliberate or not — of restricting the free exercise of religion should be subject to strict scrutiny.

Roughly translated from legalese, the courts have always recognized that some religious practices will conflict with some generally applicable laws. Strict scrutiny means that those laws need to justify themselves in order to be upheld. Oregon v. Smith said the opposite was true — it shifted the burden of proof onto the religious practices, forcing them to justify themselves while giving the benefit of the doubt to the laws that restricted them.

Specifically, proponents of RFRA and the law itself sought to re-establish the older Lemon Test — a form of strict scrutiny the courts had previously used to evaluate laws that had the effect of restricting freedom of conscience. Wikipedia’s summary of this three-part test is pretty good, so I’ll copy-and-paste that here:

- The statute must not result in an “excessive government entanglement” with religious affairs (also known as the Entanglement Prong).

- The statute must not advance nor inhibit religious practice (also known as the Effect Prong).

- The statute must have a secular legislative purpose (also known as the Purpose Prong).

Those three “prongs” include lots of other language, such as defining what it might mean to “inhibit religious practice” by considering whether a law place an “undue burden” on citizens, etc. But the important thing there is the first three words of each item: “the statute must …” Any statute that has the effect of restricting the free exercise of religion must stand in the dock and justify itself.

The Supreme Court bristled at this attempt to correct its earlier ruling and, in 1997, it found RFRA unconstitutional when applied to the states, but not when applied to the federal government.

That’s confusing — perhaps deliberately so. It has the effect of making strict scrutiny sometimes applicable and sometimes not. And it seems, these days, that whether or not the restriction of religious exercise is subject to strict scrutiny depends on whose religious exercise is being restricted.

That smells bad. It has the pungent stench of differing weights and measures — of justice for some but not for others.

But that’s the foul-smelling current state of our national discussion of “religious liberty.” In the early 1990s, the religious right fully supported RFRA because, after all, if the government could deny the free exercise rights of Native Americans, then what’s to stop it from denying their rights as well?

Twenty years later, the religious right has changed its tune. Their goal nowadays is not to ensure religious liberty for all, but just for themselves. They’re fighting for differing weights and measures.

Part of what really stinks here is the way the language of RFRA is being twisted to turn an attempt to defend the rights of religious minorities into a tool for defending the hegemony of religious majorities.

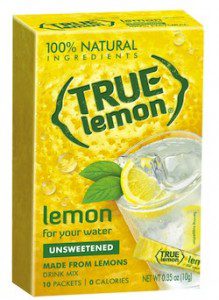

Hence, Pence. The Indiana governor just signed into law something called a “Religious Freedom Restoration Act.” But the law itself is nothing like its 1993 namesake. It’s an artificial Lemon. Indiana’s new law is not an attempt to hold statutes restricting religious liberty to strict scrutiny. It is, rather, a reaffirmation and expansion of the obnoxious logic of the Oregon v. Smith ruling that the real RFRA was written to correct. And it goes beyond that, to grant this power to discriminate not just to the state itself, but to private businesses and business owners.

In Indiana, every business is now Oregon and every customer they don’t like, for whatever reason, is now Smith.

And Smith, you’ll remember, lost.