Originally posted February 8, 2008.

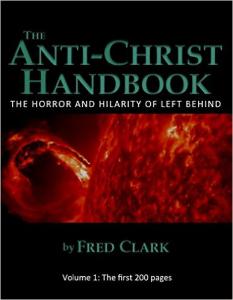

Read this entire series, for free, via the convenient Left Behind Index. This post is also part of the ebook collection The Anti-Christ Handbook: Volume 1, available on Amazon for just $2.99. Jemele Hill was correct. Volume 2 of The Anti-Christ Handbook, completing all the posts on the first Left Behind book, is also now available.

Left Behind, pp. 400-409

Buck Williams isn’t intended to be perceived here as the ever-present, unshakeable, stalker-pursuer of Chloe Steele. That role is reserved for God. We’re supposed to see Chloe here as chased by the very “Hound of Heaven.” God has tracked her down, worn her down and now, at last, we come to Chloe’s big conversion scene.

Then again, “conversion” may be too grand a word for what happens to the converts in Left Behind. None of them seems to be converted to anything. They do not become followers of Jesus, receiving and bestowing grace in pursuit of restoring right relationships with God and neighbor. Instead, they merely become believers in a series of propositions about “the Antichrist and all.” Unlike Rayford and (shortly) Buck, Chloe undergoes a change in personality following her recitation of the magic words, but the change is entirely one of subtraction, not of addition. She ceases to be “independent” (the word is used more than once as a pejorative) in her thinking, becoming mindlessly receptive and obedient. Her coming to faith is not portrayed as the conclusion of an intellectual quest for meaning by a carefully thoughtful young woman, but rather as the abandonment and rejection of that intellect, that quest, that care and thoughtfulness.

Then again, “conversion” may be too grand a word for what happens to the converts in Left Behind. None of them seems to be converted to anything. They do not become followers of Jesus, receiving and bestowing grace in pursuit of restoring right relationships with God and neighbor. Instead, they merely become believers in a series of propositions about “the Antichrist and all.” Unlike Rayford and (shortly) Buck, Chloe undergoes a change in personality following her recitation of the magic words, but the change is entirely one of subtraction, not of addition. She ceases to be “independent” (the word is used more than once as a pejorative) in her thinking, becoming mindlessly receptive and obedient. Her coming to faith is not portrayed as the conclusion of an intellectual quest for meaning by a carefully thoughtful young woman, but rather as the abandonment and rejection of that intellect, that quest, that care and thoughtfulness.

Chloe’s “conversion” is thus one of the saddest events in a book full of woes and calamities. We met her more than 300 pages ago as the spunky Stanford undergrad who somehow managed to transverse half the country, on her own, during the chaos of the aftermath of The Event. She alone voices the reasonable objection that the “God” of LB seems arbitrary, vindictive and cruelly pleased to be inflicting suffering. When that objection never gets a response, she has enough moxie to walk out of Bruce Barnes’ evasive and shallow “skeptics meeting.” And she alone sticks up for the badly mistreated Hattie Durham. All of that makes her one of the few even slightly realistic characters in the first half of the book, one of the only characters we can, or want to, relate to.

Yet after just a few days under her father’s roof, Chloe begins to change. The brave, curious, skeptical character accidentally sketched earlier is replaced with a cowering, whining child, spending days at a time sitting alone in her room, doing nothing, constantly on the verge of unconsolable tears. The change is so stark that it seems to parallel the warning signs of abuse or assault that I was taught to be on the lookout for when I worked with teenagers. The abuse, in Chloe’s case, is occurring at the hands of the authors.

Her conversion scene is intermixed with more of what passes as romantic-comedy banter between Chloe and Buck. She is charmed, moved and won over by his creepy seat-next-to-hers surprise, which she takes not just as a gesture of his affection, but of God’s. The first thing she says to him is, “Have you ever received a direct answer to prayer?”

Buck shot her a double take. “I thought your dad was the praying member of your family.”

“He is,” she said. “But I just tried out my first one in years, and God answered it.”

“You prayed I would sit next to you?”

“Oh, no, I never would have dreamed of anything that impossible. How did you do it, Buck?”

Yes, the same girl who nine days ago got from San Jose to Chicago while all commercial flights were grounded is now in awe of Buck’s seat-booking skills. But let’s get back to the wet fleece on the dry ground and the kind of faith that expects and requires a “direct answer to prayer”:

She took his hand again. “Buck, this is too special. This is the nicest thing anyone’s done for me in a long time.”

“You said you were going to miss me, but I didn’t do it only for you. I’ve got business in Chicago.”

She giggled and let go again. “I wasn’t talking about you, Buck, though this is sweet. I was talking about God doing the nice thing for me.”

They both repeat their admiration for how sincere, serious and compelling her father’s spiel had been the night before:

“If I didn’t know better, Buck, I would have thought he was trying to convince you personally rather than just answering your questions.”

“I’m not so sure he wasn’t.”

“Did it offend you?”

“Not at all, Chloe. To tell you the truth, he was getting to me.”

Chloe fell silent and shook her head. When she finally spoke she was nearly whispering, and Buck had to lean toward her to hear. He loved the sound of her voice. “Buck,” she said, “he was getting to me, too, and I don’t mean my dad.”

OK, I don’t have the power to enforce this, but I’m declaring a moratorium on any further use of dramatic whispering until Jenkins demonstrates a better understanding of when it is and isn’t effective. All this whispering makes me feel like I’m watching an M. Night Shyamalan film.

“Too bizarre,” he said. “I was up half the night thinking about this.”

“It won’t be long for either of us, will it?” she said. Buck didn’t respond, but he knew what she meant.

I appreciate that the last lines there were intended to be hopeful. She means that their salvation is close at hand. But those lines don’t seem to convey that. They seem more full of unspoken dread and foreboding, like something Dana Wynter would have said to Kevin McCarthy while hopelessly trying to stay awake in that cave in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

“When do I get to be the answer to prayer?” he prodded.

“Oh, right. I was sitting there at dinner with my dad pouring his guts out to you, and I suddenly realized why he wanted me to be there … He wanted me to get it indirectly. And I did. I didn’t hear how he started because Hattie and I were in the ladies’ room, but I had probably heard that before. When I got back, I was transfixed. …”

So it was the ladies’ room. For half an hour. The ladies’ departure from the table was presented as a significant and meaningful event. We weren’t told where they were going or what they were up to in their absence. It seemed intended as a mystery. Now here, nearly 20 pages later, we’re off-handedly informed that they were just in the ladies’ room, which doesn’t account for either the length of their absence or for the dramatic buildup surrounding their departure.

This sort of thing happens enough in LB that you sometimes get the sensation you’re reading one of those group-written take-a-turn stories in which each writer contributes succeeding paragraphs. Also, what is it with LaHaye & Jenkins and rest rooms? (Feel free to supply your own Larry Craig joke here, but let the easy ones pass.)

“It wasn’t that I was hearing anything new. It was new to me when I heard it from Bruce Barnes and saw that videotape, but my dad showed such urgency and confidence. Buck, there’s no other explanation for those two guys in Jerusalem, is there, except that they have to be the two witnesses talked about in the Bible?” Buck nodded.

That’s nodded in agreement, I think, not nodded off to sleep because he’s exhausted and Coke is a woefully inadequate caffeine-distribution device and here we go again with the Steeles and their sleep-inducing obsession with the Jerusalem street preachers, although the latter would have made more sense.

It’s easy to miss the subtle dismissal above of Irene Steele. Chloe hears her manly man father’s urgent and confident presentation of prophecy mania and she’s shaken to the core. But she doesn’t even remember that every word he said was something she had heard previously, over and over again for years, from her mother. “It was new to me when I heard it from Bruce Barnes,” she said. No, it wasn’t. I’m not sure whether the authors, too, have forgotten all about Irene’s years of obsessive witnessing to her husband and daughter, or whether they’re just suggesting that a woman can’t be an evangelist. Either way, Irene turns out to have been so inept and ineffectual at spreading her prophecy gospel that it’s a wonder she even qualified to be Raptured.

Next we get another 20-pages-later explanation, confirming what I’d pretty much expected about why Chloe was — unnoticed and without explanation at the time — crying at dinner the night before:

“So, Dad and God were getting to me, but I wasn’t ready yet. I was crying because I love him so much and because it’s true. It’s all true, Buck, do you know that?”

“I think I do, Chloe.”

“But still I couldn’t talk to my dad about it. I didn’t know what was in my way. I’ve always been so blasted independent. I knew he was frustrated with me, maybe disappointed, and all I could do was cry. I had to think, to try to pray, to sort it out …”

Curse all that blasted independence and thinking and sorting things out! We — thankfully — are spared an explicit portrayal of Chloe’s prayer of conversion, but if the pages leading up to it are any indication, these are the very things she confesses as sins and repents of.

“I’ve been convinced,” she said, “but I’m still fighting. I’m supposed to be an intellectual. I have critical friends to answer to. Who’s going to believe this? Who’s going to think I haven’t lost my mind?”

Intellectual pride can be a sin, of course, but it is not the only sin. Nor is intellectual pride and having an intellect the same thing. Yet Chloe, like Rayford before her, treats the very possession and use of her intellect as the foremost of her sins. This form of confession strikes me as itself a violation of the first commandment: “Love the Lord your God with all your mind.”

“I got on this plane, desperate for some closure, pardon the psychobabble, and I started wondering if God answers your prayers before you’re … um, you know, before you’re actually a …”

“Born-again Christian,” Buck offered.

“Exactly. I don’t know why that’s so hard for me to say. … I prayed and I think God answered. …

“Chloe, what exactly did you pray for?”

“Oh, well, the prayer itself wasn’t that big of a deal, until it was answered. I just told God I needed a little more. I felt bad that all the stuff I’d heard and all that I knew from my dad wasn’t enough. I just prayed really sincerely and said I would appreciate it if God could show me personally that he cared, that he knew what I was going through, and that he wanted me to know he was there.”

And then she turned and found Buck sitting next to her. “It was as if God knew better than I did that there was no one I would rather see today than you,” she tells him, and gives God full credit for a direct and specific answer to prayer.

So this is what it takes to impress her. The Event and the Israel Miracle didn’t stir her in the least. The Trip and Die Guys she found impressive, but not sufficient. But this — this tangential-at-best maybe-response to the vaguest of vague requests — this she treats as proof beyond any reasonable doubt. This conversion of Chloe’s would make very little sense in any other setting. In this setting, in this story, it makes no sense at all.

She announces her intention to recite the magic words and invites Buck to join her, prompting this bit of dialogue that reads like it was lifted from a Very Special Episode of Blossom:

Buck hesitated. “Don’t take this personally, Chloe, but I’m not ready.”

“What more do you need? … Oh, I’m sorry, Buck. … If you’re not ready, you’re not ready.”

It’s here that Chloe has the flight attendant summon her father to hear her “extremely good news.” We cut back to Rayford’s point of view because this is how Jenkins works: If Chloe sends her father a message, the next scene has to be of her father receiving that same message. This is part of his secret formula for cramming a 200-page novel into a mere 468 pages. He really could have skipped the three-paragraph detour into Rayford’s perspective here, and we’ll skip most of it too, except for the first sentence —

Rayford was manually flying the plane as a diversion when his senior flight attendant gave him the message.

— just so we can do our best Butthead impression. “Heh heh. Heh. Heh. He said manual diversion.” (Juvenile, yes, but the opening sentences of the book — “With his fully loaded 747 on autopilot …” — introduced the jumbo jet as surrogate penis motif, so don’t blame me.)

We quickly return to Buck’s POV, which is the next best thing to fading to black for sparing us from the intimacies of Chloe’s spiritual ecstasy.

[Buck] peeked back at Steele with his daughter, engaged in intense conversation and then praying together. Buck wondered if there was any airline regulation against that.

Buck Williams may not yet be ready to declare himself a born-again RTC, but he’s already acquired their persecution complex. There must be an airline regulation against praying — probably even a federal law — because, you know, Christians in America are so often made to suffer for their faith. Those first-century Christians had it so easy by comparison. That’s why John’s Apocalypse wasn’t written for or about them, you know, but for and about us 20th- 21st-century American Christians. And only us 21st-century American Christians.