So, OK, let’s talk about “progressive evangelicals.” That’s not a perfectly accurate description, but it might be the best attempt to give a name to something real and identifiable.

Thirty years ago the phrase would have been “liberal evangelicals.” This wasn’t what they called themselves, but a label assigned to them by others. It was meant to be dismissive — a way of further marginalizing the few voices within white evangelicalism who were emphasizing economic justice, or “concern for the poor,” or who were modestly calling for “racial reconciliation” or for something closer to equality for women.

“Liberal evangelicals” is what those folks were called by conservative white evangelicals, who were happy to promote the misleading notion that a liberal-to-conservative political spectrum aligned perfectly with a liberal-to-conservative theological spectrum.

This is one of the more successful lies of the religious right — one they’ve gotten a great deal of the media and the wider public to accept uncritically. The implication is that the further to the right one is politically, the more orthodox and genuine one’s religious beliefs must be. So any supposed “Christian” who didn’t believe in unfettered laissez-faire capitalism, increased military spending, trickle-down economics, a repeal of the “excesses” of civil rights law, and the legal presumption of male supremacy wasn’t “really” a Christian at all, just a “liberal” masquerading as a Christian who probably didn’t even believe in Jesus, or the resurrection, or the Bible, at all.

It was an attempt to portray anyone with any sympathy for any kind of “liberal” politics as something other than a legitimate Christian. This is a weird lie, ridiculous on its face. It’s pretty audacious to claim that, say, Pat Robertson takes Jesus more seriously than Dorothy Day did. But despite that, it has proven a very effective lie for religious “conservatives” of all stripes — i.e., for politically reactionary people who seek religious and moral authority as a way of enforcing their political agenda.

The old label of “liberal evangelical” was intended to promote that lie — to suggest that these folks weren’t really evangelicals at all, just adherents of some post-Christian “liberal” theology. It was meant to insinuate that, say, Jim Wallis was secretly a devotee of Paul Tillich or of John Shelby Spong (a favorite religious-right bogeyman from the ’90s). It didn’t matter that Wallis went to TEDS* and probably has never read a full chapter of Tillich in his life.

Wallis, the founder of Sojourners magazine and the Sojourners community, is probably the most famous representative of “progressive evangelicalism.” That subset of white evangelicalism was, for years, often summed up as Jim, Ron and Tony — referring to Wallis, Ron Sider, and Tony Campolo. More broadly it also included folks from dozens of other Sojourners-like “intentional communities” all across America, such as the folks at Jesus People USA in Chicago. Plus all of the authors and academics who initially endorsed the “Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern” back in 1973. Maybe also the network of parachurch nonprofits affiliated with the Christian Community Development Association. And stretching a bit, we could also include folks like the “egalitarians” of Christians for Biblical Equality, the Kuyperian think tank Center for Public Justice, and even the larger evangelical relief and development agencies, like World Vision and World Relief.

These are all evangelical people and groups. They are part of the world of white evangelicalism. They come from that world, and they want to remain in it. And while all of them have been subjected to plenty of criticism from their fellow white evangelicals — often receiving the warning-label of “controversial” — the gatekeepers of that world have never quite excluded them entirely or attempted to banish them with an official “farewell.”

No one in any of those so-called “liberal” groups appreciated the attempt to marginalize and delegitimize them through the use of the label “liberal evangelicals,” so the nomenclature eventually shifted in search of something less dismissive. “Evangelical left” was thus tried on for a while, even though this was also ill-fitting. Yes, some of those simple-lifestyle, intentional communities were, in a sense, Christian communes, but they weren’t intent on overthrowing capitalism, just in dropping out of it.

“Evangelical left” did make for a nice contrast with “religious right.” It caught something of the way religion reporters in the 1990s all seemed to have Jim and Ron and Tony in their rolodexes as go-to sources for quotes they hoped would provide a bit of “balance” to stories otherwise dominated by religious-right perspectives.

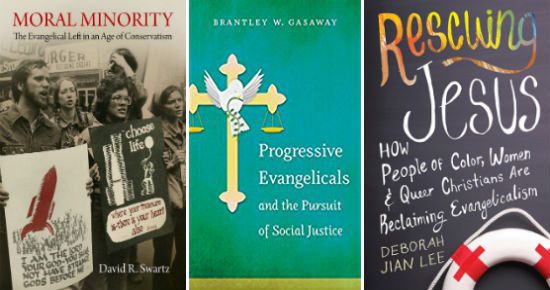

This was the term David Swartz used for his 2014 history, Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism.** Swarz’s account covers the usual suspects, but also includes folks like Richard Mouw and Fuller Seminary, and the idiosyncratic politics of Sen. Mark Hatfield and Rep. Paul Henry (both were Republicans — Republicans who varied slightly and occasionally from a strict loyalty to the Reagan Republicanism of their era, but still). Those folks might not have been aligned with the religious right, but they hardly constitute anything that could meaningfully be described as a “left.”

There’s an obvious “Overton window” problem there. Views closer to a muddled middle of the political spectrum get reclassified as “the left,” thereby redrawing the boundaries to exclude any actual left as beyond the pale. If Richard Mouw and Fuller Seminary is where we’re going to peg “the left,” then we’d have to regard J.R. Daniel Kirk as the equivalent of Huey Newton and Rachel Held Evans as Subcomandante Marcos. That would be wildly inaccurate. (Kirk was pushed out at Fuller, but he’s not a “leftist” by any measure, let alone a far leftist. And it’s weird to even have to say this, but neither is Rachel, despite the efforts of some patriarchal Christian nationalists to portray her as Public Enemy No. 1.)

“Evangelical left” terminology doesn’t avoid the problem of conflating the left vs. right political spectrum with a spectrum of left vs. right theology. This confusion is, again, deliberately exploited based on the implicit notion that “liberal” means illegitimate/apostate and “conservative” means orthodox.

So maybe it’s best to avoid any sort of political left/right terminology as inherently flawed here?

Think, for example, of the Amish. Are they theologically “conservative” or theologically “liberal”? Good luck trying to employ those labels in any meaningful way here. The Amish are Anabaptist sectarians — at once both fiercely anti-traditionalist and traditionalist, anti-hierarchical and hierarchical. They rigidly enforce their own strict theology, which seems “conservative,” but that theology varies greatly from that of the historical creeds and doctrines of the larger church, which seems “liberal.”

And are they politically “conservative” or politically “liberal”? Well, they’re radical pacifists, but also crushingly patriarchal. They’re simultaneously capitalist and anti-capitalist. If the only map we have for them is our idea of a left-right, liberal-conservative spectrum, then the Amish are all over the map.

To a lesser extent, that’s also true of the folks we’re trying to identify as “liberal evangelicals” or the “evangelical left.” It’s tempting, then, to abandon all talk of political spectrums and retreat to something like H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture typologies. I might do that if I had any confidence in our ability to apply those without sliding into Forer-effect absurdity.

And ultimately we keep falling back into the language of a political spectrum because politics really is what makes this sub-set of white evangelicals distinct. That’s true even for those Anabaptist-y or hippie-ish factions that are determinedly non-political (the Ellul/Vanier/Neuwen types, etc.) because politics — explicitly partisan politics — is a core aspect of identity for the rest of white evangelicalism. Partisan politics may not be the main distinctive of the white “evangelical left,” but it is the paramount distinctive of the larger white evangelicalism from which it is distinct.

So until something better suggests itself, I’ll fall back on a political-ish terminology and employ “progressive evangelicalism.” That’s still ill-fitting — a not-quite-right description of something that’s not-quite-left. But I suppose it will have to do.

This is also the term Brantley Gasaway uses in his 2014 history Progressive Evangelicals and the Pursuit of Social Justice. Gasaway, a religious studies professor at Bucknell, knows this little world very well. He understands its boundaries, and the way those boundaries are being perpetually negotiated, and renegotiated, and reinforced.

He’s also the guy I’m going to be quoting at length to set the stage for the next part of this discussion, now that I’ve finished this throat-clearing introduction about the frustrating inadequacy of terminology.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, an unquestionably evangelical seminary in Deerfield, Illinois. I’m sure I wasn’t the only evangelical who was briefly confused the first time I clicked on a video of a TED Talk and was puzzled by why TEDS had invited this person to lecture there.

** Full disclosure: I have not yet read either Swarz’s book or Brantley Gasaway’s. This seems inexcusable, and I intend to read them, eventually, really I do. But I’m still trying to get past the … oddness of doing so. For me, personally, reading these books would be like reading a history of the New York Mets if you also happened to be Ed Kranepool.