At the time of our Visitation it was two O’clock in the morning, the night after the Carmelite feast of Holy Father Saint Elijah. As on most feast days, I’d been too sick to pray the Divine Office; now that it was night, I was wide awake, worrying. My husband Michael was downstairs, reading. Our daughter was asleep. The windows were open, because it was hot and we couldn’t afford air conditioners. All was quiet as the tomb.

Then I heard a voice cry out in the darkness. “Get out of here, you bastard!”

My husband’s voice. At this hour he was either shouting at a drug-addled burglar, or a stray cat. Steubenville has plenty of both. The house we rent used to be a crack house, and I was always afraid that a drug addict would come back here one night, looking for a fix. I’d wished we had a gun for just such an occasion, but we couldn’t afford a gun any more than we could afford air conditioners or secure window screens. There are also a myriad of stray cats in the neighborhood; old ladies leave salad bowls of cat food on their porches, and the cats roam about the streets free and healthy and unnervingly bold. This is a mercy, since the neighborhood is also infested with rats. But it’s not without its dangers. Michael is allergic to cats; cat dander blocks up his sinuses and leaves him miserable for days.

“Don’t you dare go near those stairs!” cried Michael. I only heard one set of footsteps pounding upstairs, one cry of frustration and one set of footsteps pounding down. That settled it. There was a cat in the house.

When I got to the kitchen, Michael had the cat cornered in the laundry room with the one unopened window in the house– unopened, because it was painted shut and wouldn’t budge. One angry leap from the cat, and then their positions were reversed; Michael was huddling in a corner of the laundry room, clutching a broom, and the cat was in the doorway, clinging to the top of the swinging door.

I can’t even tell you how Michael ended up wheezing on the living room sofa, but that is what happened next. We were all reacting on blind instinct at that point. The cat was still clinging to the swinging door, suspended between Heaven and Earth, kitchen and laundry room, leaving deep claw marks in the landlord’s new paint.

Animal Control does not answer nighttime calls in Steubenville, and the police don’t answer any number after hours except 911. Besides, I knew the policeman who patrolled this part of the LaBelle neighborhood, and he was not the sort of man I wanted to see the state of my kitchen at two O’clock in the morning. There was no one to deal with the situation but me. There never is. Michael had several desperate ideas for how to scare the cat back outside, but didn’t expect further displays of force to work any better than the previous had, so I went into the kitchen myself.

I shut the doors to the kitchen and opened the door to the outside, hoping the cat would just leave, but he was too afraid to let go of his perch.

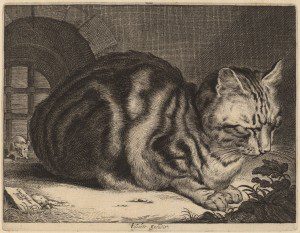

He was the biggest cat I had ever seen, a full-grown tom with a charcoal gray smoking jacket, white gloves and a white cravat. His green eyes regarded me with that particularly feral kind of terror, pleading for mercy yet ready to scratch out my own eyes if I turned on him.

“Hello,” I said.

I offered him a hot dog. He sniffed it, but did not bite.

I noticed that the cat had a white triangle on the bridge of his nose, like the peak of Mount Carmel.

“May I call you Elijah?” I asked respectfully.

The cat did not object.

Poverty and tuna go together; we had six cans in the cupboard. I opened a can and placed it on the floor. Elijah remained petrified on top of the swinging door, letting “I dare not” wait upon “I would” like the old cat in the adage. I wondered what adage Shakespeare was talking about, and if anybody remembered. I had read a great deal of Shakespeare growing up, in a big non-annotated coffee table book, but I had never had anyone to explain it to me. I had never seen a cat let “I dare not” wait upon “I would” until this moment. I accepted that Elijah was far more afraid of my fat, chronically ill, pajama-clad frame than I was of his teeth and claws, and I tried to radiate tranquility.

I stepped closer, and held the tuna can up to his nose. He ate, nervously, jerking up to stare at the refrigerator and back at me for reassurance every time the condenser made a noise. I spoke to him the way one does to cats, complimenting his soft fur and, eventually, stroking his quivering side. Twice I tried to pick him up, and twice he dug his claws in further. Twice I apologized and gave him more tuna. We went on like this for close to an hour. Finally, he allowed me to hold him. I carried him to the back steps, where he leaped from my arms and disappeared into the night.

I left the can of tuna on the step. I came inside, Elijah’s hair covering my pajamas, wondering if I had inherited a double portion of his gift. As if the opportunity of giving hospitality on the feast of Holy Father Saint Elijah were not a gift enough.

Forgive me. This post was meant to be a sermon on the virtue of meekness, but I’m no good at sermons. Still, you ought to be gentle with everything that comes to you. And if Elijah returns before we speak again, remember that he likes tuna better than hot dogs.

(Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art).