It has likely come to your attention that the Holy Father has made a change to the Catechism’s passage on the death penalty, and everybody’s got something to say about it. Some people are thrilled. Some people are incensed. Some people curiously are claiming that the Holy Father has no right to change the Catechism. They seem to have forgotten that the Catechism did not come down the mountain inscribed on stone tablets carried by Moses. This catechism was composed in response to a request submitted by the 1985 synod of bishops to Pope Saint John Paul II, issued in 1992 under his direction, and reissued by John Paul II in a revised edition in 1997. He meant for it to be revised. The purpose of the Catechism is to expound the faith. The purpose is revising it is to expound the faith more effectively. Ask JPII if you don’t believe me.

Right and wrong never change, of course. They can’t. But our understanding of what constitutes the right and wrong can evolve. Clarifying and evolving that understanding, and noting the clarification in the Catechism, is one of the things the Magisterium, with the Holy Father right at the top, is supposed to do. Direct killing is always wrong, whereas some things that look like killing, such as self-defense, are permissible in some circumstances. The Pope has further evolved what counts as direct killing and is therefore impermissible.

The Catechism used to read:

Assuming that the guilty party’s identity and responsibility have been fully determined, the traditional teaching of the Church does not exclude recourse to the death penalty, if this is the only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor.

If, however, non-lethal means are sufficient to defend and protect people’s safety from the aggressor, authority will limit itself to such means, as these are more in keeping with the concrete conditions of the common good and more in conformity to the dignity of the human person.

Today, in fact, as a consequence of the possibilities which the state has for effectively preventing crime, by rendering one who has committed an offense incapable of doing harm – without definitely taking away from him the possibility of redeeming himself – the cases in which the execution of the offender is an absolute necessity “are very rare, if not practically nonexistent.

That version is still what it says online right now, at least as of the time I’m typing these words, and I don’t know when they’re going to change it.

With the Pope’s amendment, the text will now read:

Recourse to the death penalty on the part of legitimate authority, following a fair trial, was long considered an appropriate response to the gravity of certain crimes and an acceptable, albeit extreme, means of safeguarding the common good.

Today, however, there is an increasing awareness that the dignity of the person is not lost even after the commission of very serious crimes. In addition, a new understanding has emerged of the significance of penal sanctions imposed by the state. Lastly, more effective systems of detention have been developed, which ensure the due protection of citizens but, at the same time, do not definitively deprive the guilty of the possibility of redemption.

Consequently, the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that “the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person”, and she works with determination for its abolition worldwide.

Now, it’s clear from actually reading the text that this isn’t a huge change from what was there before. The death penalty used to be allowed, at least theoretically, in extreme circumstances if it was the only way to protect the public. It was considered a form of defense rather than direct killing in that case. The amendment to the text just points out that such a case doesn’t really exist anymore, rendering the death penalty as it is applied in modern times unnecessary– and, therefore, forbidden.

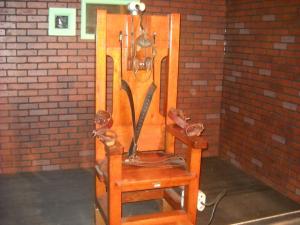

What I want to point out is that we were never allowed to just fry somebody for vengeance, or because the person deserved it. That hasn’t changed.

That’s something you’re never allowed to do, because direct killing is always wrong.

My friend Mark Shea often makes the comparison between people who fearfully ask when we, as Catholics, might “have” to kill somebody and people who excitedly ask when we “get’ to kill somebody– as though most people are looking for an excuse not to kill and some people are looking for an excuse to kill. That’s a comparison that’s not without its merit. If you frame an ethical question to make it about whom you’re allowed to harm, you’re not being the least bit ethical. A life properly lived shouldn’t be about harming anybody.

As for me, I have a different way of looking at the same thing. The way I understand the teaching of the Catholic Church, is that you never have to kill, nor are you allowed to kill, any people, ever. Killing is always wrong. There are a slim number of circumstances wherein it is permissible to respond to a deadly attack against oneself or another with deadly force; if the aggressor dies in that circumstance, you commit no sin. It’s still not a good situation. If the would-be killer lives, that would be much better, because death is always a tragedy and always something to be avoided. Far better, of course, if the situation never occurred in the first place– a situation where one person attempts to take another’s life is always a tragedy. But at bare minimum if he dies from your act of self-defense, that’s not on you.