A few weeks ago, one of my loved ones underwent surgery, and was prescribed an opioid painkiller. Although he chose not to take it, this got me thinking about how our society strives to eliminate all pain, and the tragic public health crisis this has created.

The financial origins of the opioid crisis

The development of opioids (not surprisingly) was motivated by financial profit.

In 1996, a pharmaceutical company named Purdue Pharma – owned by the three Sackler brothers – introduced OxyContin. This is a time-released formulation of oxycodone, a strong narcotic pain reliever. The Sackler brothers used their status as physicians to (falsely) tout this new drug as having little risk of addiction, despite strong evidence of its addictive power. Purdue marketed OxyContin with an aggressive advertising campaign and funded biased research to support it. The firm also used a bonus system to incentivize OxyContin sales by its representatives.

This strategy succeeded; opioid sales reached $1.1 billion by 2001.

The philosophical origins of the opioid crisis

Although these financial origins are widely acknowledged, there is one often-neglected factor that was key to the escalation of opioid use: dogmatic materialism among medical experts.

Allow me to explain.

Throughout history, medical professionals have used four vital signs in monitoring their patients.

- Body temperature

- Pulse rate

- Respiration rate

- Blood pressure

These vital signs provide objective indicators of health because they signal the status of the body’s life-sustaining functions.

In 2000, this changed. The Joint Commission (the organization responsible for hospital accreditation) labeled pain as the “fifth vital sign” and issued new Pain Management Standards. Throughout the nation, the Standards suddenly required health care providers to manage all reported pain. Furthermore, they added questions about pain management to patient satisfaction questionnaires. Ratings scores affect a physician’s reimbursement rate, so this placed strong pressure on physicians to liberally prescribe painkillers.

The creation of the “fifth vital sign” rests on a materialist view of the human mind. I don’t mean the kind of “materialism” that involves rampant online shopping, but the “materialism” that has you convinced that physics can explain everything in the world. This philosophical doctrine is called reductive materialism.

Proponents of reductive materialism believe that all mental states can be identified with physical states. In the case of pain, materialists hold that pain just is the firing of certain nerves called “c-fibers,” nothing more. If this materialist position is correct, then it makes sense to use pain as the fifth vital sign, because it simply provides an objective indicator of the status of the body.

The costs of materialism

This materialist understanding of the mind is wrong. Pain is not just neural firing. Though most pain may be realized in the brain through its c-fibers, pain is something more than neural firing. Thomas Nagel, in his essay “What is it like to be a Bat?”, calls this the subjective character of experience. Knowledge of this phenomenal aspect of pain is only possible from the first-person standpoint of the person who is suffering.

Anyone who has suffered pain knows this to be true. Your spiritual and mental health greatly influences your pain. Pain arises in the context of your other beliefs, symptoms and experiences. Reducing pain to a mere vital sign disregards these truths of human nature.

The costs of this philosophical mistake are shockingly high. The estimated national economic cost of the crisis is upwards of 1 trillion dollars. As of 2016, about 2 million US residents are addicted to prescription opioids. So far, there have been at least 600,000 deaths from overdoses on these drugs, and almost 200,000 more expected by 2020.

These skyrocketing numbers show the real human costs of getting human nature wrong.

Responding to the opioid crisis

So what do we do?

Our attention must shift upstream. The war on drugs has become a war on drug users, when instead we should focus on pharmaceutical companies and health care providers.

Ultimately, though, only a cultural shift away from materialism will heal this epidemic. We must foster a society that recognizes and understands pain in the context of the flourishing of the whole human person. This means we need to care for the spiritual, social, and mental well-being of all who suffer pain.

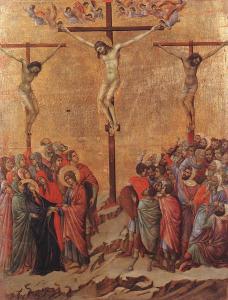

Christianity can help us get there, because it tells a different story, one that utterly up-ends the materialist conception of pain.

God chose to save the world from within through the Incarnation. God took our human condition upon Himself, in all its frailty and weakness. Christ embraced the Father’s will though it caused Him to experience the pains of betrayal and abandonment, and even the agony of the Passion. This act elevated the whole of our embodied existence. In this way, all of our human condition – even pain – has become an invitation to conformity to Christ.

In his Apostolic Letter Salvifici Doloris, St. John Paul II says that suffering is “essential to the nature of man,” because it belongs to our transcendence. Because of this ultimate meaning, we don’t have to eliminate suffering. I’m not suggesting that we not treat pain, but rather that the goal of medicine should be holistic wellbeing rather than the mere elimination of pain. We can overcome reductive materialism. The Incarnation gives us this strength, for it communicates the grace we need to live our weakness according to the Mystery of Redemption (2 Cor 12:7).

Further reading

Thomas Nagel’s essay, “What is it like to be a bat?” presents his challenge to physicalism.

JP II’s Salvifici Doloris explains the Christian meaning of human suffering.

This NY Times article is a groundbreaking indictment of Purdue Pharma, the company at the origin of the opioid crisis.