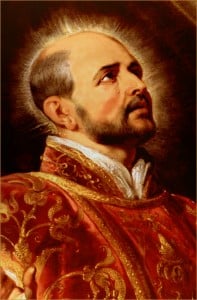

“There are very few people who realize what God would make of them if they abandoned themselves entirely into his hands, and let themselves be formed by his grace.” St. Ignatius, whose feast we celebrate today, wrote that in 1543. Four hundred and seventy-one years later, that fundamental Ignatian insight that God is far more active than we are often willing to notice or trust is still valid — and, inasmuch as it has formed the current successor of Peter, very much at work in the Church.

“There are very few people who realize what God would make of them if they abandoned themselves entirely into his hands, and let themselves be formed by his grace.” St. Ignatius, whose feast we celebrate today, wrote that in 1543. Four hundred and seventy-one years later, that fundamental Ignatian insight that God is far more active than we are often willing to notice or trust is still valid — and, inasmuch as it has formed the current successor of Peter, very much at work in the Church.

A couple of weeks ago, PEG argued that that the collective hysteria over Francis speaking off the cuff and granting interviews is misplaced. As he put it, most analyses have been assuming either that (a) Francis really wishes to radically revise the teaching of the Church, and the interviews are part of his master plan to begin doing so or (b) that Francis is faithful to the tradition, but somehow so clueless that he doesn’t recognize how his interviews can be used, dangerously, to undermine the Church’s teaching.

Against these interpretations, PEG proposed a third explanation: “Francis is an orthodox Catholic who knows exactly what he’s doing.” One of the proofs for this claim was “the fact that he’s a Jesuit, and Jesuits are always playing three-dimensional chess.”

Now, I certainly think that Francis is an orthodox Catholic, and knows what he’s doing, and as a Jesuit I’m flattered that the reputation of the Society for strategy and sophisticated thinking is intact (after all, it’s step 14 in our secret plan for world domination).

Our sources tell us the joke was not actually about world domination.

But in all honesty, I think there’s a simpler explanation for what Francis is doing — he doesn’t need to have the entire end-game plotted out in advance, and he knows he doesn’t need to, because that’s God’s job.

The simpler explanation is another expression of that basic Ignatian insight that we began with — the 15th annotation to St. Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises. The “annotations” are a set of instructions to the director of the retreat, and the 15th basically tells the director to get out of God’s way. Here it is in full (emphases added):

The one giving the Exercises should not urge the one receiving them toward poverty or any other promise more than toward their opposites, or to one state or manner of living more than to another. Outside the Exercises it is lawful and meritorious for us to counsel those who are probably suitable for it to choose continence, virginity, religious life, and all forms of evangelical perfection. But during these Spiritual Exercises when a person is seeking God’s will, it is more appropriate and far better that the Creator and Lord himself should communicate himself to the devout soul, embracing it in love and praise, and disposing it for the way which will enable the soul to serve him better in the future. Accordingly, the one giving the Exercises ought not to lean or incline in either direction but rather, while standing by like the pointer of a scale in equilibrium, to allow the Creator to deal immediately with the creature and the creature with its Creator and Lord.

Promote a particular approach to the Christian life, counsel perfection, urge people to greater fidelity — all these are “lawful and meritorious.” But once a person is engaged in seeking God’s will, then get out of God’s way — and trust that God not only can communicate himself, but that it is far better that God does communicate himself than that you, the director, the one “in the know,” explain and clarify everything.

Now, of course the context of the Spiritual Exercises and someone electing a state of life is a very particular one, but the core insight is the same. God is actively at work among his creatures, actively communicating himself, and our main task is to facilitate that contact — not to explain it, clarify it, channel it, or ratify it. When “God in all things” is used to describe Ignatian spirituality, that’s what it refers to, not some Hallmark feel-good pablum.

Perhaps you hear an echo of this approach in Francis’s first and most famous off-the-cuff remark: “A gay person who is seeking God, who is of good will — well, who am I to judge him?” This is not dangerous moral relativism; this is not even lazy moral equivalence. This is profound confidence that God is at work with people who are seeking him. It’s the insight of the 15th annotation, applied to the present situation of the Church and the world.

The reason Francis is so “uncareful” in interviews — or to take PEG’s reading, the reason he is so “deliberately shocking” — might not be some grand master plan; it might not involve a prediction of how this will all turn out. Francis’s hope — and I’ve said this before — is to get us to pay attention to God and to seek him out. Beyond that is God’s business. That doesn’t mean that anything goes; it doesn’t mean that the teachings of the Church get tossed out the window and truth becomes subjective.

But it does mean that we don’t get to go into hysterics when things get messy; it does mean that we don’t defend and clarify the teachings of the Church so obsessively and self-righteously that we crowd out God’s self-communication to those who are seeking him.

Francis does have a strategy, and he certainly has priorities; but I really don’t think he has a master plan. What he has — shaped by his Jesuit formation and Ignatian spirituality — is a radical confidence that God is at work among his people, and that God’s master plan, even when we don’t understand it, is far better than anything we would come up with on our own.