Welcome to the 6 month study group on Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. All comments are screened. Disagreement is fine. Incivility will not be tolerated. Subscribing via RSS and subscribing to comments is recommended. You may join the group at any time.

Welcome to the 6 month study group on Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. All comments are screened. Disagreement is fine. Incivility will not be tolerated. Subscribing via RSS and subscribing to comments is recommended. You may join the group at any time.

For more information please read this linked post. Discussion on the Introduction and Chapter One is here. Scroll through my blog entries for the remaining chapter readings and discussions.

______________________

“The mass incarceration of people of color is a big part of the reason that a black child born today is less likely to be raised by both parents than a child born during slavery.”

– Michelle Alexander, New Jim Crow, Ch 5

This chapter was a hard one for me to write about, in a book difficult to discuss. I keep just pulling quotes, instead of synthesizing, or drawing out information, or reaching conclusions. The only conclusion that arose while going over chapter five is that I feel angry. Angry at where we are with this horrible, human eating system of mass incarceration. Angry at how difficult it feels to counter this system – which is interlocked with so many other systems of oppression and disenfranchisement – and to grow a culture that allows for healing, and is based on respect.

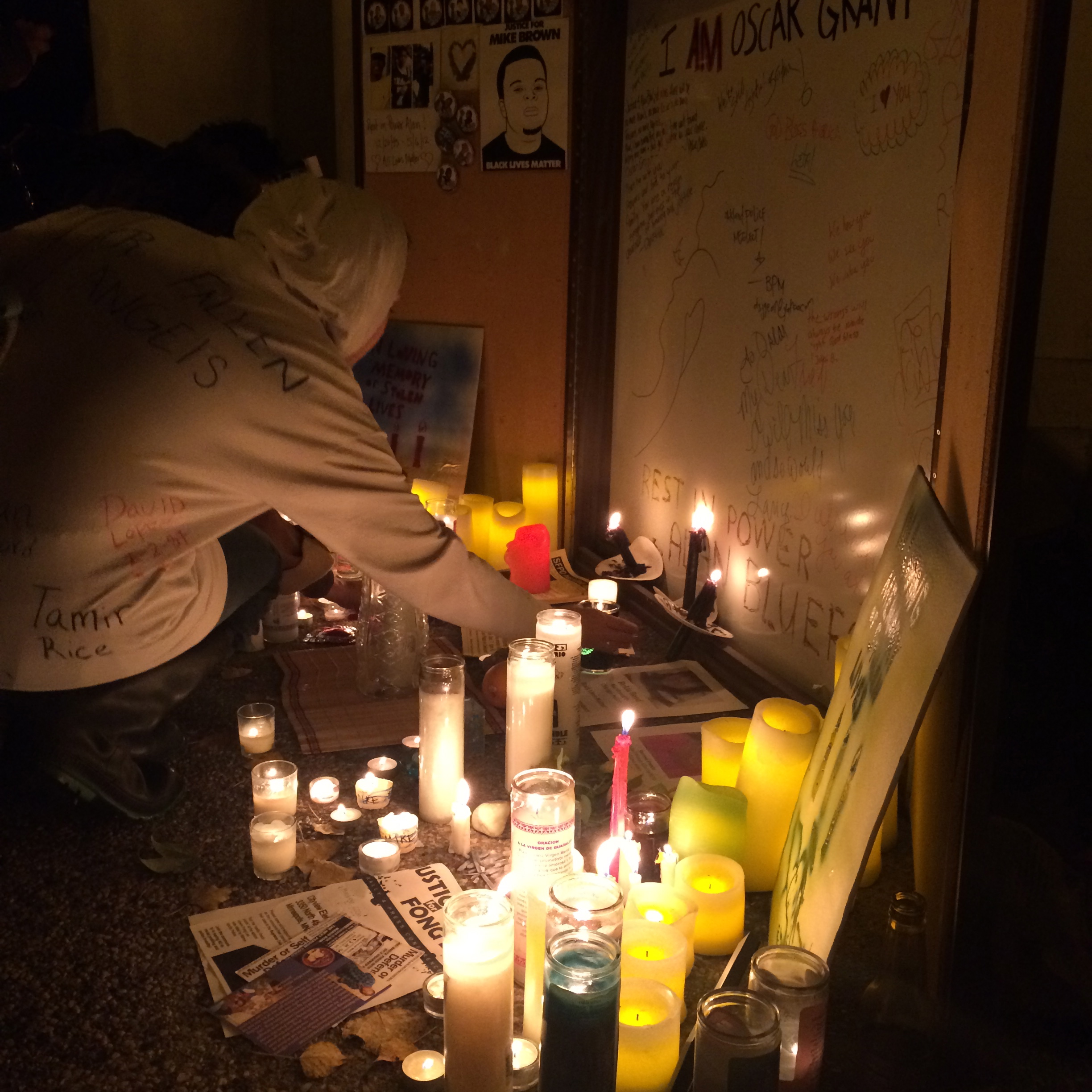

Angry, too, because it has been more than a month after Mike Brown’s murder, and the Ferguson protests are still going on because nothing has been done. Just today, the police raided the camp of some young protestors – the Lost Voices – arresting those whom they see as activist leaders.

Report after report keeps coming in from around the country showing our police are indeed out of control.

This behavior is not coming from all officers, certainly, but it is not just a “few bad apples” either. It is an Egregore built over time. The behavior of police terrorizing and killing citizens is the direct result of training and a shift in policies over the last decade. The training comes from such events as Urban Shield – which I’ve protested the last two years – and the International Association of Chiefs of Police. The policy shifts started with Clinton and have been rolled out and expanded since.

It is time for change.

But it is still too easy to blame the victims. Especially when we see the victims as criminals.

“The message was a familiar one black men should be better fathers. Too many are absent from their homes.” (NJC)

With no question as to why. The why is that too many men are in prison. The why is that too many men are disenfranchised.

“They have abandoned their responsibilities.” Or have they themselves been abandoned?

“…There were more black men in [Illinois] correctional facilities [in 2001] just on drug charges than the total number of black men enrolled in undergraduate degree programs in state universities.” (NJC)

The system is “race neutral” yet is enforced using racial discrimination.

As DuBois said: “the burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting the great wrongs.”

We need to dismantle corrupt and punitive systems. We need to build communities based on healing and restorative justice. There must be truth. And there must be reconciliation. Only then, will communities heal and families and friends be reunited.

We must remember that love is still the law.

And sometimes that love arises from great anger.

_______________

Questions for Contemplation and Discussion:

(All questions adapted from the New Jim Crow Study Guide)

1. White Privilege

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens’ Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a nega- tive peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice…” Dr. King

Is it still true today that many whites prefer “order” to justice? What can be done to bring about a fuller acknowledgement of white privilege in our society and its far-reaching, often devastating con- sequences? What can be done to cultivate more con- cern, understanding, and cooperation across racial lines?

2. Collateral Damage

In chapter five, Alexander states that white people are “collateral damage” in the War on Drugs—not the original target, but harmed nonetheless. Do you agree? Who else is harmed by the drug war but might nevertheless believe it is in their interests? Borrowing again from Dr. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” how can we help awaken people of all colors to the reality that we are “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny”? Do you agree with King that “whatever affects one directly, affects all”?

3. Racial Indifference

Many would argue that mass incarceration is different from Jim Crow because of the lack of overt racial hostility. Alexander acknowledges that, unlike the days of Jim Crow, few people today are proud to call themselves racist. On page 203, she writes: “Things have changed . . . [and] this difference in public attitudes has important implications for reform efforts.” But on the whole, Alexander maintains that mass incarceration depends far more on racial indifference thanracial hostility. Do you agree that mass incarceration is rooted in racial indifference—a lack of care and concern across lines of race and class? If so, how do we inspire greater compassion and care? Research suggests that people interpret and understand the world through stories. Do the stories of those trapped in the system need to be told and heard? What else can be done?

Beginnings of Action

A New Underground Railroad

In numerous speeches, Alexander has argued that we should commit ourselves to building an “underground railroad” for people returning home from prison. Movement building, she argues, requires working for the abolition of the system of mass incarceration as a whole, as well as providing desperately needed support and love to people at risk of incarceration, families with loved ones behind bars, and people returning home from prison. The movement must acknowledge and respond to the human suffering caused by this system and model what a compassionate society actually looks like. Do you agree? If so, what can we do, individually and collectively, to offer greater support, resources, and love to people struggling to survive the system of mass incarceration?

Further Reading:

Alexander details many systems of oppression in US history. For more information, I recommend reading Ta-Nehisi Coates: The Case for Reparations. I wish this had a stronger ending, but it is well worth the read for the history alone.