Next month will mark twenty years since Monica Lewinsky was subpoenaed by lawyers for Paula Jones, who was suing then-President Bill Clinton for sexual harassment. It was the moment the president’s private affair left the confines of the Oval Office and made its way into the public, where it would ultimately lead to his impeachment.

It was common then to hear those in the Republican camp, especially evangelicals, proclaim that “character counts.” Bill Clinton’s behavior, they said, and his willingness to lie about it, made him unfit for high office. This disgust, along with the widespread belief that Hillary Clinton helped cover up her husband’s alleged conquests and even assaults, planted the seed that festered for decades and blossomed into an unprecedented show of distaste toward the Clintons in the 2016 election.

It was common then to hear those in the Republican camp, especially evangelicals, proclaim that “character counts.” Bill Clinton’s behavior, they said, and his willingness to lie about it, made him unfit for high office. This disgust, along with the widespread belief that Hillary Clinton helped cover up her husband’s alleged conquests and even assaults, planted the seed that festered for decades and blossomed into an unprecedented show of distaste toward the Clintons in the 2016 election.

Last year also turned out to be an unprecedented display of irony. Because the alternative on the ballot was a man whose personal history and proclivities strongly resembled Bill Clinton’s. Yet evangelicals overwhelmingly supported him, and helped elect him president, despite eleven-year-old recordings which surfaced of the GOP nominee boasting about boorish, inappropriate, and potentially illegal behavior.

After the election (the outcome of which—full disclosure—I did not expect), I made two general predictions about voter attitudes and evangelicals’ moral scruples. The first was that President Trump would cost the Republican Party in future elections, setting it on roughly the same course Obama set the Democrats on in 2008 when their majorities in both houses and their governorships began to evaporate.

This month’s elections, by all accounts, were triumphs for Democrats, who won key races in Virginia and New Jersey. On the grand scale of national politics, the victories were small, but if they’re a foretaste of next year’s midterms, Republicans have reason to be uneasy. And with President Trump’s approval rating at a historic low less than a year into his presidency, the party’s tea leaves don’t look good.

The second and more important prediction I made was that evangelicals would lose not only moral authority to speak out on issues like adultery in the oval office, but that they would stop caring about the morality of public officials, altogether. The lesser-of-two-evils calculus so many Christian leaders advanced in urging their followers to support Trump would take on a life of its own, justifying less and less savory candidates, and ultimately divorcing evangelicals’ professed morality from their voting habits. If they committed themselves deeply to excusing Trump’s “locker room talk,” I reasoned, they would soon excuse anyone for anything, as long as they perceived him as part of their tribe.

Fast-forward a year, and I’m not exactly eating crow.

Beverly Young Nelson was the fifth woman to step forward to publicly accuse Judge Roy “Ten Commandments” Moore, who is running for U.S. Senate, of sexual misconduct. She claims he tried to rape her when she was sixteen and he was a thirty-something prosecutor in Etowah County, Alabama. Her allegations are consistent with two others from last week that portray a younger Moore as a man unhealthily interested in girls half his age. Nelson’s account also adds a new dimension of violence and aggression to that image. Her story corroborates Leigh Corman’s original accusation that Moore sexually assaulted her when she was fourteen. All told, nine women—all of whom were in their teens at the time of the alleged incidents—are accusing Moore of acts that range from creepy to criminal. The pattern, established when the Washington Post broke the story earlier this month, is obvious.

Moore denies everything (well, sort of). His most devoted supporters are also digging in, insisting that we presume their man “innocent until proven guilty,” and pointing out how politically convenient the timing of these accusations was.

This second defense isn’t much help. After all, virtually all political scandals could be called “convenient” for the opposing side. The Monica Lewinsky scandal was enormously convenient for Republicans, and contributed to a decades-long perception of the GOP as the party of morality. It didn’t matter. The charges against Bill Clinton were true, convenient or not.

The first defense—which I’ve watched numerous otherwise smart conservatives take up—confuses legal concepts with plain commonsense. The presumption of innocence, due process, and other judicial standards for proving guilt don’t apply outside of a court of law, and definitely aren’t appropriate bases for deciding how to vote. We should of course treat people fairly and use discernment. False accusations of sexual misconduct, while rare, do happen. But attempts to turn accusations against Moore into a “he-said-she-said” situation ignore the fact that there are now nine accusers. This is more of a “they-said-he-said” situation.

More importantly, to insist that none of these charges have any merit also requires a conspiracy of staggering size. If Moore’s accusers (the first few of whom were sought out by the Washington Post) are lying, it means one of the nation’s largest newspapers has staked its reputation and business on a provable falsehood, and convinced at least nine women—some of whom are Republicans and voted for Donald Trump—to do likewise. It even means one of Moore’s latest accusers (Nelson), forged the yearbook inscription she produced as evidence for the good judge’s inordinate interest in her, with no apparent motive.

All of this, rather than admit that a man who replied, “Not generally, no,” when asked whether he dated teenagers in his thirties, is probably guilty.

It’s difficult to imagine another politician who could be credibly accused of sexual misconduct by so many women, be black-listed by his hometown mall cops for “badgering teenage girls,” all but admit to this pattern of behavior on a conservative radio show, and still enjoy a spirited defense from erstwhile members of the Moral Majority.

These, for the most part, are the same folks for whom Paula Jones’ charges against Bill Clinton are gospel—for whom Hillary Clinton’s rumored criminal shenanigans might as well be God’s Word inscribed on stone tablets—and who’ve happily believed accusations against Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, Al Franken, George Takei, Louis C.K., and Bill Clinton. For some reason, anti-establishment Republican Roy Moore gets the benefit of more doubt than all of these progressive men combined. How “convenient.”

Only next month’s election will show for certain, but I may actually be understating the level of evangelical allegiance to Moore, whether he’s guilty or not. According to a poll that came out before Nelson held her press conference, 37 percent of Alabama evangelicals say they’re more likely to vote for Moore after the first four allegations. Just 28 percent said they’re now less likely to vote for him.

As Rod Dreher points out, these folks aren’t thinking, “Oh happy day, I can vote for a child molester!” They’re thinking, “If liberals hate Moore, [I] love him even more.”And that, Dreher concludes, is moral corruption—“loving worldly power over righteousness.” It’s compromising our moral witness and responsibility to promote just leadership in order to spite the other side.

Let’s be clear, here: If the allegations and witnesses against Moore at this point had been leveled at Moore’s Democratic opponent (Doug Jones), every conservative evangelical in the country would have united in condemning him and calling him to withdraw from the race. They would have little trouble accepting this overwhelming evidence. They would admit the obvious.

Yet some defending Moore have gone beyond maintaining his innocence, and have begun arguing that the things he’s accused of doing aren’t really so bad.

Alabama State Auditor Jim Zeigler hung a lovely dead fish around Christians’ necks when he compared Roy Moore’s teenage victims to the virgin Mary, who “was a teenager” when Joseph, a carpenter of unspecified age, married her. “There’s just nothing immoral or illegal here. Maybe just a little bit unusual.”

The familiar “lesser of two evils” logic has also come trotting out. “Even if Moore did sexually assault several teenage girls,” one vocal Moore supporter told me recently, “his opponent supports killing babies. Keep your eye on the dammed ball. You’re allowing yourself to be lectured about the evils of sex with children [by] people who sanction the legalized slaughter of children.”

Apparently, we have to choose between heeding the sixth and seventh commandments when it comes to politics.

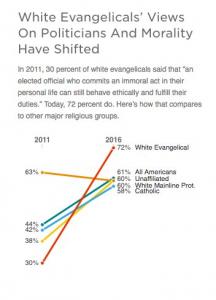

The common trend here is a catastrophic breakdown in the evangelical belief that morality matters in office—that “character counts.” What prominent Christian leaders said following the Monica Lewinsky scandal is simply no longer a reflection of their convictions on the subject. According to a poll last year by the Public Religion Research Institute, in 2011, just thirty percent of white evangelicals agreed that “an elected official who commits an immoral act in their personal life can still behave ethically and fulfill their duties.” In 2016—in the runup to the presidential election—a staggering 72 percent of white evangelicals agreed with that statement.

In the course of five years, America’s largest and most conservative group of Christians underwent a revolution on the importance of character in public office. White evangelicals have gone from the most morally scrupulous group of American voters to the least. Along the way, they’ve abandoned a belief that once united them in calling Bill Clinton “unfit for office.” To borrow a quip from Albert Mohler, they owe the former president an apology.

If a candidate opposes abortion, evangelicals don’t seem terribly concerned with what else he says or does. There is no longer a bar below which a candidate is “unfit for office.” Or if there is, that bar is low enough that someone credibly accused of sexual assault against teenage girls can clear it.

Nothing seems able to shake evangelicals’ allegiance to “outsider” candidates with an “R” beside their names. Certainly not a belief in a God big and sovereign enough to honor a principled abstention or third party vote on election day—the True Judge Who wrote the Ten Commandments and Who isn’t a “respecter of persons,” or for that matter, parties.

It’s obvious that the religious right of 2017, if transported back to 1997, could not consistently call for Bill Clinton’s impeachment. Conservative Christians have long since abandoned the standards they advanced back then in favor of a cold realpolitik that treats moral character as a nice but unnecessary frill. All that really matters, in this new moral calculus, is getting our guy in office and keeping the other guy (or gal) out. Although such tolerance for sexual immorality is not new to the Oval Office or the U.S. Senate, it is surprisingly new to the evangelical church.

Image: Bill Clinton visiting Los Alamos National Laboratory, Wikimedia Commons

Image: Former Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court Roy Moore, BibleWizard, Wikimedia Commons

Articles at the Troubler of Israel Blog are the responsibility of G. Shane Morris and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Colson Center for Christian Worldview.