MONDAY WAS THE 86TH ANNIVERSARY of the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., so I thought I would share some thoughts about his life and legacy.

My first encounter with Dr. King’s reputation as a public figure was as a student at my predominantly black elementary school in Richmond, California. I was 6 years old in 1968, and watched a replacement for Pullman Elementary rising from an immense patch of dirt in a cordoned-off corner of the school yard. Dr. King was felled by an assassin’s bullet on April 4 of that year, so when our shiny new school opened the next fall it was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School in honor of King’s life and struggle.

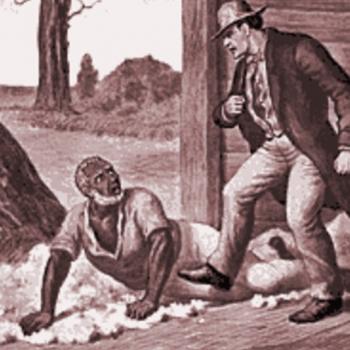

Growing up in a black neighborhood gave me insight into Dr. King and his effect on the lives of black Americans that is unusual for a middle-class white kid. Many of my neighbors had come from the Jim Crow South. There were people in my neighborhood who had lost relatives to lynchings. They had come from a place where whites could, at any moment and for reasons that may or may not be intelligible, suddenly turn on and attack a black man. It was a place where a black man could be put to death for some real or imagined violation of the racial hierarchy, and where his killers would typically suffer no legal consequences.

But even more subtle forms of oppression were deeply wounding to the minds and souls of my neighbors. There was a man in the neighborhood, the father of some friends of mine, who had made an offer on a house in the (white, middle-class) El Cerrito hills. When the people in that neighborhood got word that a black man might move there with his family, they pooled their resources and bought the house out from under him. My father said at the time that he had never seen anyone so hurt.

While anger and bitterness were certainly an understandable response by blacks to centuries of oppression and injustice — and the 1960s had its share of both — Dr. King called for a response that was far more subversive and creative than retaliation:

And then the Greek language comes out with another word; it is the word agape. Now agape is more than romantic love. Agape is more than friendship. Now agape is understanding creative redemptive goodwill for all men. It is an overflowing love, which seeks nothing in return. Theologians would say that it is the love of God operating in the human heart. And when one rises to love on this level, he is able to love the person who does the evil deed, while hating the deed that the person does. And he is able to love those persons that he even finds it difficult to like, for he begins to look beneath the surface and he discovers that that individual who may be brutal toward him and who may be prejudiced was taught that way — was a child of his culture. At times his school taught him that way. At times his church taught him that way. At times his family taught him that way. And the thing to do is to change the structure and the evil system, so that he can grow and develop as a mature individual devoid of prejudice. And this is the kind of understanding … that the nonviolent resister can follow if he is true to the love ethic. And so he can rise to the point of being able to look into the face of his most violent opponent and say in substance, do to us what you will and we will still love you. We will match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. And do to us what you will, and we will still love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws because non-cooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. And so throw us in jail, and as difficult as that is, we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children and as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators and violence into our communities at the midnight hours and drag us out on some wayside road and beat us and leave us half-dead and we will still love you. But be assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer. And one day we will win our freedom: but we will not only win freedom for ourselves. We will so appeal to your heart and your conscience that we will win you in the process and our victory will be a double victory.

The essence of Dr. King’s mission was reconciliation, not retribution. He and his movement sought power not for its own sake, but to serve the agenda of love:

What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.

Dr. King sought not only to end de jure racism in the South and elsewhere, but to fundamentally transform American society into what he termed “The Beloved Community.”

More on that in part 2.